Carl Chiarenza on Boston Photography

Harvard Dissertation on Aaron Siskind First on Photography in US

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 07, 2019

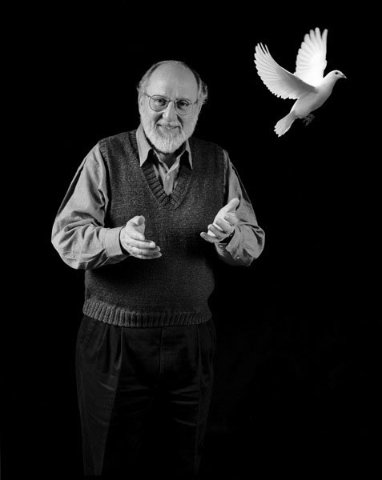

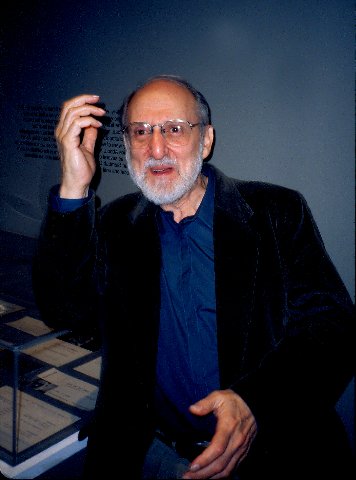

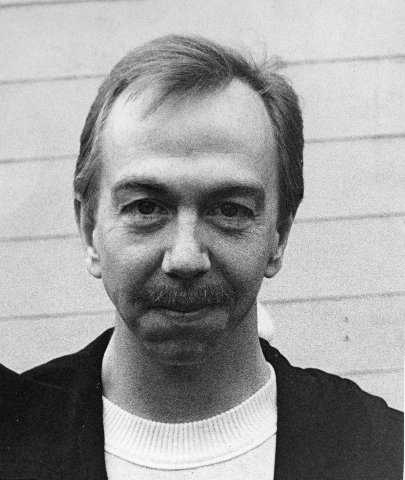

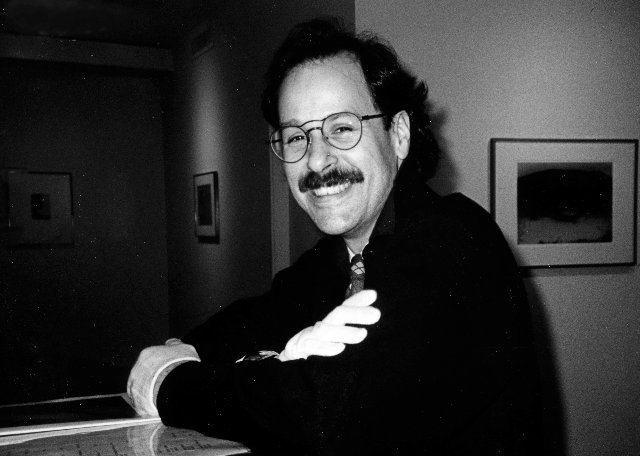

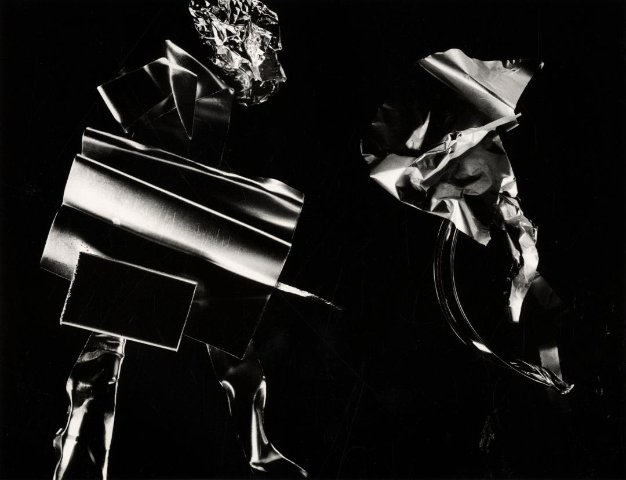

During graduate study at Boston University photographer Carl Chiarenza was a professor, mentor and friend. We spoke at length about how JFK and the Vietnam War nudged him into studying art history. At Harvard he was the first American to write a dissertation on photography. It was a biography and critical study of then living American icon Aaron Siskind. Now retired from the University of Rochester he continues to create new work.

Charles Giuliano From your e mails I gather that you are busy.

Carl Chiarenza I’m still making work but not worrying about selling it. I have been donating work to museums. Albright Knox Museum recently took nineteen. The Portland Oregon Museum probably got about the same number. The connection there was the photographer Stu Levy. He has some of my work traded over the years. He lives in Portland and helped me offer them my photographs. He made arrangements for things they wanted. I made suggestions for things they didn’t have. I don’t have everything anymore.

My current exhibition at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (May-November, 2019) is of work I donated. I don’t make more than twelve prints of any image. Mostly I don’t make more than five.

CG Are the five to a dozen prints all made at the same time?

CC Not always. If I’m in the darkroom I may make three. Or I may make five but I rarely make more than five at one time. If I sell the five, or they go somewhere, I may make more if I think that picture is worth reprinting.

CG To make prints at a later time do you keep a notebook with the settings?

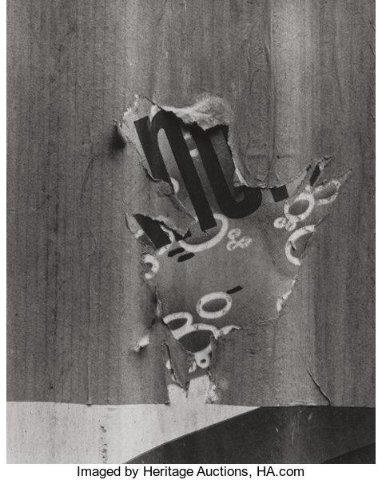

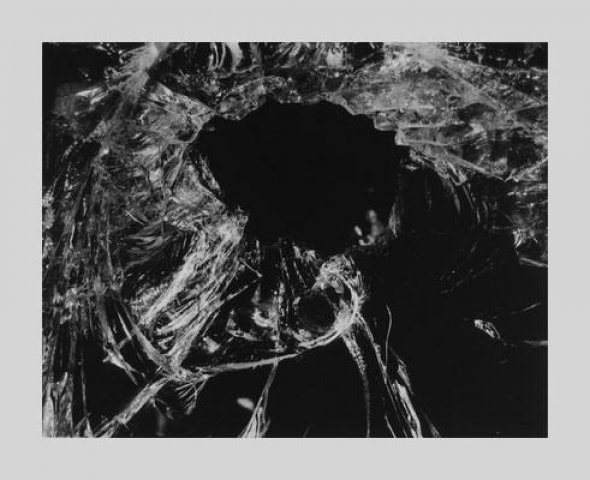

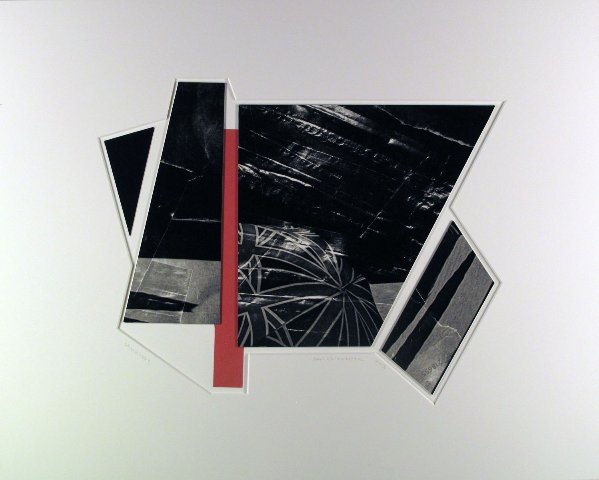

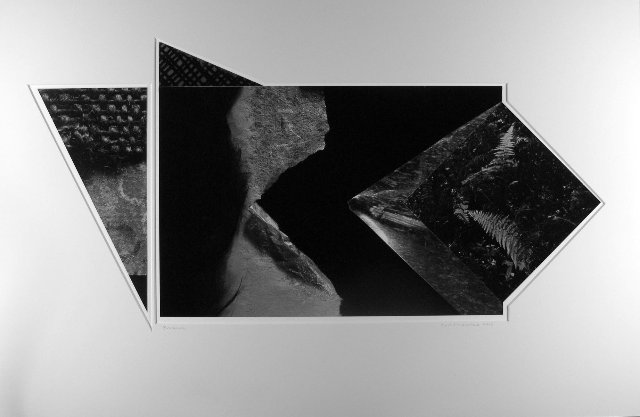

CC I have about twenty-five darkroom work notebooks. They include contact prints and information about printing. For the past two years I have not had any of my traditional film which disappeared when the Polaroid Corporation folded long ago. I have been making one-of-a-kind collages from rejected prints and odd papers that I have collected and assorted items people give me. I tear and rip them up and use them as collage material.

CG Are you photographing digitally?

CC No. But I am not against it. Many of my friends are making wonderful digital work. I’m about to be 84 and don’t want to start using digital media. I’m still printing negatives that haven’t been printed before. Mostly I’m making the one-of-a-kind collages. They entail torn photographs and torn pieces of paper I’m dry-mounting and pasting things together on a board as any collage-maker would do. At my website you can see a selection of the collages.

CG In addition to Albright Knox, Portland, and Virginia, are you donating to other museums?

CC I’m in many collections. Museums have bought much of my work over the years. Donations are just what’s going on as I age. You can see the list of my public collections on my website.

CG What are your estate plans?

CC I will leave all that to my wife and kids. What I’m doing with donations is to simplify this. Several thousand of my books are now in the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City. They recently inherited the Hallmark Collection of photographs, and they had almost no photography books in their library. I’m trying to clear out the house so that when I do go the kids won’t have a hell of a mess. I gave fifteen boxes of photography magazines and exhibition catalogs, etc. to the Visual Studies Workshop here in Rochester. Their students can now have access to them. I didn’t give them books because they have an incredible library. There are probably six to eight museums that have received donations of prints.

CG What of your scholarly papers and documents?

CC When I first retired from University of Rochester twenty years ago Debi Martin Kao, one of my students, was the curator of photography at Harvard Art Museums. I was on the collections committee at the Fogg Art Museum for many years. Debi asked me the same question that you just did. I told her “If you’re interested send a truck and empty out my office.” The paper work went to Harvard’s Houghton Library archives. I had a cabinet with many drawers of slides I made over the years. They took all the slides, books and paper work I had there but nothing from my house. That was twenty years ago and I haven’t done anything with that kind of material since. I’m trying to decide whether to call them and see if they want the rest of the stuff. Or should I leave it to the George Eastman Museum? I haven’t decided yet.

CG You did your dissertation on (Aaron) Siskind. Where would one find those documents?

CC The Siskind dissertation research material is all at the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona. I think there’s some at Archives of American Art (Washington, D.C.). The Center in Tucson has a major collection of Siskind’s work. I thought it would be wise to give them the information. The dissertation became the source material for my book called Aaron Siskind Pleasures and Terrors.

CG Correct me if I’m wrong but you were the first to earn a PhD in art history based on a living photographer.

CC I have been told that I was the first person in the United States. Aaron Scharf (1922-1993) wrote a book called Art and Photography, which I reviewed for The Art Journal (volumes 31, 1972. issue #3). I think that book was based on his dissertation produced in England before mine. But I was probably the first in this country. Scharf was the first in the world.

CG What was Harvard’s response when you proposed it?

CC My initial proposal was to do for photography what (Ernst) Gombrich had done for painting (The Story of Art). They turned that down because they didn’t think that photography was ready for that kind of project. I got pretty upset about that. My advisor was Jim Ackerman and he was then in England. I wrote to him and said how about if I do a biography and discussion of the work of Aaron Siskind?

He wrote back and said “I can’t get excited about a living artist, particularly not a photographer.” So I started working on other people at the Fogg and finally convinced one of them. The person who helped the most to get it accepted was Agnes Mongan the curator of drawings. I did a lot of work with her and wrote a piece on photography and drawings by (Edgar) Degas. She liked it very much and got it published in Master Drawings. She helped me to get the department to approve the dissertation topic. Ackerman came around to allow that to happen. So it took a little effort.

CG You went on to see through many dissertations on photography.

CC I wouldn’t say many. I didn’t keep track, but perhaps ten or so.

CG Compared to none that’s a lot.

CC Those people are teaching or curating at various colleges and museums (e.g. Mary Panzer) around the country.

CG You were a part of overcoming the prejudice against photography as a legitimate field for art history. I have been working with Pat Hills on a chapter for my next book. She described the struggle of getting American Art accepted as a legitimate field of study.

CC Yes that’s right.

CG She discussed her tenure battle at BU. That points to a Eurocentric bias in art history.

CC Yes, but that certainly changed. In recent times art history departments have focused more and more on sociology and theory. And now the art market is more like the stock market and that too has changed art history. That has me less interested and less involved.

CG Can you flesh that out?

CC Why does this quote regarding the auction of a work by Jeff Koons (“The price, surpassing … $90.2 million with fees achieved, again at Christie’s…”) upset me? Because, among other reasons, so many of the people spending that kind of money are not putting the art on their walls. The work is going into warehouses waiting for the price to go up.

So, yes, I am upset with what has happened within the art world during my lifetime. That’s why I am now donating my work to museums rather than still trying to sell it. Collectors are still buying work because they respond to it and not to its investment profit potential, but I’m not working very hard at it.

CG How does the shift of emphasis on the collector and market impact the fields of art history?

CC That’s a good question, but I have not had a direct connection with teaching for twenty years; so I don’t really know what’s going on within art and art history departments. What I read about prices in newspapers and on the internet lead me to see little or no relationship between aesthetic and financial analyses. That has pretty much gone out the window. I can’t really answer the question about what’s going on with teaching or museums. You are no doubt aware of how museums are tied up with money.

Every time I offer a print to a museum the first question is “Is it a vintage print?” Why would they want a vintage print? They say it is because it is closest to what the artist was thinking at the time. That seems reasonable until you think about how the artist may have improved printing over the years. If it is a later print, it may be a lot better as a picture than one that’s called ‘vintage.’ They really don’t care about the print being better than the first. They just want the first. An artist friend of mine’s long ago response to the vintage question (& I love it) was “Tell me what vintage you want and I’ll make it for you.”

CG That raises questions about works, like those of the Diane Arbus estate, which were printed by technicians. She was known to be a not particularly good printer. That’s true for a number of photographers, particularly photojournalists. My friend the poet/photographer Gerard Malanga has never set foot in the darkroom. He has published books and had many successful exhibitions. Lee Friedlander, for example, acquired and printed the glass negatives of the New Orleans photographer John Ernest Joseph Bellocq. The Library of Congress continues to print and sell depression era photographs.

CC Yes Friedlander printed Bellocq’s work. I don’t think (Henri) Cartier-Bresson printed his own work. Many photographers do not, and didn’t. I’m talking about my printing or many other artist’s (e.g. Jerry Uelsmann’s) printing. Even when we make large format works with a lab and independent printer, we are there working and supervising the printing. We must do the printing because much of the final image depends on what we do to it in the darkroom. I never let anyone print my work without my being there.

CG What becomes of your negatives? Will you authorize them being printed posthumously?

CC I will not authorize reprinting by anyone. They will very likely be destroyed

CG When were you writing your dissertation?

CC 1960s, early 1970s. When I was doing my dissertation Davis Pratt was dealing with photography in the Harvard museums at the time. We did the first major photography exhibition at Harvard. It was called The Portrait in Photography. Following that, a committee was organized regarding the collection of photography at Harvard. I was on that committee for many many years. We tried to get some funding for photography at Harvard. We applied to the National Endowment for the Arts for funding to buy photographs. The head of the NEA at the time wrote to me and said “Well, we had never considered photography in our funding. But it’s an interesting idea. Why don’t you apply again next year?” We did and that’s what got us funding to start the collection and do that exhibition. From that point on we had a committee dealing with photographs. Davis Pratt was the photography collection’s first curator.

The only way I could keep my job at BU was if I got a PhD. I had been there for three years. I didn’t want to leave Boston. So, other than my own department at BU the only other place I could get a PhD was at Harvard. Through miracle after miracle after miracle the dean at BU helped me to apply to Harvard. There was a grant for faculty who wanted to do a degree beyond what they had. I think it was called The Danforth Fellowship. He applied for that for me and I got it. That seemed to impress Harvard and they took me for some peculiar reason. Harvard also gave me a fellowship. So it was just one miracle after another.

The only reason I got into art history was due to Jack Kennedy. After I got my master’s in journalism my intention was to make a living as a photojournalist. But, as soon as I got my degree I was drafted. After two years I was supposed to be discharged but President Kennedy froze all discharges because of the Berlin crisis. I went all over the base looking for someone who knew how to get around that. An officer in personnel said that, it’s a long shot, but if you can get admitted to a graduate program by January they will let you out. I was due to be discharged in December. I said how in hell am I going to do that? I started calling people at BU asking can you get me a scholarship starting with the second semester? Bill Jewell, who was head of the art history department at the time, agreed to do that. To this day I don’t know why. Since I got the scholarship I decided I would do a semester of art history and then get on with my work as a photojournalist. At the end of the semester they offered me another scholarship. I decided I had nothing better to do for a year or so and I stayed on. At the end of that they offered me a job.

Three years later they (BU) said you need a PhD. I had never planned to be an art historian. I remember telling you to forget about getting a PhD.

CG I remember that conversation well and all of what you said proved to be true.

CC I never intended to get a PhD. I just wanted to make art and make a living. So it’s all Jack Kennedy’s fault.

CG Going back to when master photos sold for under a hundred dollars what are the evaluations today? What would an Aaron Siskind print sell for at that time?

CC Probably about $45. Prices barely covered expenses. Do you remember the Carl Siembab Gallery? In the 1950s Siembab showed Siskind, Ansel Adams, Dorthea Lange, Edward Weston, Minor White, and other famous makers. The prices ran from twenty five to fifty dollars per print. Nobody was buying photographs. Siembab was one of the first galleries on the East Coast to sell photographs. When he retired I did an exhibition about his gallery at Boston’s ICA (1981). We showed work by all the people I just mentioned. Because I curated the show it did not include my own work. The show’s catalog has an informative text about the gallery by Lee Lockwood, chronologies of the gallery's exhibitions, and of photography in Boston from 1924 to 1981; and a preface by me.

About prices: for the most famous Ansel Adams print, “Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico,” 1941, I have no idea how many prints there are. The current price is about $30,000. I had an Edward Weston print I bought for $200 in the 1960s. Decades later, needing money, I sold it at auction for $40,000 and that print sold recently for $150,000. The prices have gone up and up and up.

CG In the Belinda Rathbone biography of Walker Evans, as I recall, he sold his negatives and vintage prints for something like $10,000. They were in shoe boxes under his bed.

CC That’s very likely. By the way, Belinda later became a member of the collections committee at Harvard.

CG It seems that overall photography in Boston was more widely accepted and appreciated than painting and sculpture. By that I mean on a critical and curatorial level. Can we say that Boston was a pretty good photography town?

CC It was after the late 1950s largely due to Carl Siembab. In the mid 1960s, I edited a little magazine called Contemporary Photographer. It was started in the very early 1960s with its first editor, Tim Hill. The second editor was D.W. Patterson; then Lee Lockwood, and then I became editor. While I was editor, Nick Dean and I discovered that Boston’s MFA owned some Stieglitz prints. We went there one day to see them. They were surprised and didn’t know where they were. Later we got a call that they found them and asked if we wanted to see them. So Nick and I went to see these prints. They took us down to the basement. There they opened a drawer in a dresser. In that drawer were the Stieglitz prints. Nick wrote an article about them which I published in Contemporary Photographer.

CG As I understand it, that set of prints was given to Ananda Coomaraswamy (22 August 1877 – 09 September 1947) by Georgia O’Keeffe. They were nudes of her taken by her husband Alfred Stieglitz. At the time, Coomaraswamy was curator of the Asiatic Department. His belief that living artists did not belong in the MFA had a sustained impact on the collections. When Perry T. Rathbone was director from 1955 to 1972, at least initially, he was regarded as progressive. It’s not surprising in that context that the Stieglitz prints were buried in the basement. [????] Of course, now, they are the pride and joy of the photography collection which has slowly come to be disentangled from the Department of Prints and Drawings. It’s an infamous story. That was the beginning. Later they received a major selection of photography: The William and Saundra Lane Collection.

CC That was a really important happening. The curator of the Lane Collection, Karen Haas, continues as its curator at Boston’s MFA. She was a graduate student in our department at Boston University.

CG Didn’t Cliff Ackley expand his portfolio from curator of prints and drawings to include photography.

CC He did, when we began to raise hell and he did act forcefully. Since then the staff has increased considerably.

{The photography program at the MFA dates to 1924 when Alfred Stieglitz gave 27 of his photographs. (The “official”version of the donation) “The Museum’s first photographic purchases were made in the 1960s when Clifford Ackley, joined the curatorial staff. In 2001 the Museum established the first curator dedicated to photography, Anne Havinga. She had been a curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs. Karen Haas, Lane Curator of Photographs, joined the department at the same time. The department grew with the additions of Kristen Gresh, Estrellita and Yousuf Karsh Curator of Photography. The Friends of Photography group was created. Through the Herb Ritts Foundation the MFA established a gallery for photography in 2008. Exhibitions range from historically based to those that are thematically diverse. Major acquisitions include early French and British photographs, turn-of-the-century photographs, the Lane Collection of more than 6,000 photographs including Edward Weston, Charles Sheeler, Ansel Adams, and Imogene Cunningham. The collectiom includes European postwar abstraction, Bruce Davidson’s original East 100th Street, Nicholas Nixon’s complete suite of the Brown Sisters, archives of the work of Yousuf Karsh and Herb Ritts, and contemporary photography by Nan Goldin, Marco Breuer, Dawoud Bey, and Hiroshi Sugimoto, among others.”}

CG Today the MFA is well known for photography. Is that true?

CC Yes. They now, as you indicated above, have a major collection.

CG How would you describe Boston's photography community around 1968 and early 1970s?

CC The DeCordova Museum did a major exhibition Photography in Boston: 1955-1985, (September 16, 2000 - January 21, 2001).

MIT Press published an impressive catalog/book, edited by Rachel Rosenfield Lafo and Gillian Nagler. It included: Berenice Abbott, Harry Callahan, Paul Caponigro, Marie Cosindas, Harold Edgerton, Nan Goldin, Jerome Liebling, Nicholas Nixon, Barbara Norfleet, Olivia Parker, Rosamond Purcell, Aaron Siskind, Minor White, and me.

The period from 1955 to 1985 reflects photography's acceptance as an art form, the influence of modernism, and the coalescence of a unique constellation of educational institutions, museums, and technological development in the Boston area that directly influenced artistic options for photography. The Siembab Gallery, the ICA, Minor White's arrival at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1965 to run the Center for Creative Photography, and the Polaroid Corporation's innovative support of photographic art suggest how developments built upon one another to create a regional critical mass in photography.

CG At the time I asked Lafo why she did not include Marc Morrisroe (1959-1989) or Doug and Mike Starn (born 1961). All three were working prior to 1985 so they fit the time line of the exhibition. I was stunned when she said “I don’t think they were important.” She was dead wrong. That was too often the case with DeCordova’s exhibitions and its curators under former director Paul Master-Karnik. The museum was, however, the major player for showing and collecting contemporary New England artists. That was by default due to the apathy of the ICA, MFA and other museums.

{There was a 1996 ICA exhibition The Boston School curated by Lia Gangitano (Editor), with Stephen Tashjian (Illustrator), Philip Lorca-DiCorcia (Photographer), Nan Goldin (Photographer), Jack Pierson (Photographer), Shelburne Thurber (Photographer), David Armstrong (Photographer) Mark Morrisroe (Photographer).}

CC There’s a lot of information in there (DeCordova catalogue essays by A. D. Coleman, Rachel Rosenfield Lafo, Arno Rafael Minkkinen, and Kim Sichel.) That museum began showing photography very early on. I was in one of their first photography exhibitions.

CG Are you in their collection?

CC I think so. I don’t remember.

CG Are you in the MFA collection?

CC I am but I don’t remember what they have. Not much. I offered them prints but I haven’t heard anything. John Szarkoswki bought one print in the 1960s for MoMA. I was in two or three shows there. They do now have more and I think that’s because I gave them prints.

CG We’re talking about Boston, but Providence is not that far away. There was Callahan at RISD.

CC And Siskind.

CG Did they spill over into Boston?

CC No, they stayed pretty much in Providence. The RISD Museum has a good photography collection. They have a lot of Siskind and Callahan, even some of mine. The Worcester Museum had a photography curator. RISD , Fitchburg, Mead, Smith College, and others now have photography curators.

CG Can we talk about Minor White and the impact he had?

CC When he came to MIT in 1965, Wayne Anderson was still there teaching modern art. He may have had something to do with Minor coming. Minor started the photography program and had assistants coming and going over the years. One of them was Peter Laytin. He is about to retire from teaching at Fitchburg State. Peter is very knowledgeable about what happened at MIT. One of my students (Lisa de Lima), was Minor’s secretary for a long time.

Minor, obviously, was not a typical MIT person. He was gay and had a unique approach to teaching. He created a program which produced a number of interesting photographers. And he curated several significant exhibitions there.

CG From what I understand he became ill and there was dissatisfaction with the program on the part of MIT. He died in 1976. The program had a new director but wasn’t sustained.

CC That’s true but you should talk with Peter Laytin.

CG Harold Edgerton was at MIT.

CC Yes, but that was very different. He was more in the science area doing research on motion. He was more scientific and technical.

CG Were you part of a unique Boston photo community?

CC I guess you could call it that, but it was part of a larger art community. Have you heard of the Heliographers? (The Association of Heliographers lasted from 1960 to 1965.) There was Walter Chappell. He had worked at Eastman House with Minor. He got a bunch of us together and there were meetings. The group included Marie Cosindas, William Clift, Paul (?) maybe. That group did a major exhibition in New York at the Lever House. (1963). Walter put it together and got it framed for free by Nielsen. Later the major photo gallery in New York was the Witkin Gallery. (Opened by Lee Witkin in 1969) It was influenced by the Siembab Gallery and became a major gallery for photography. There were a few in the 60s before that. Dave Kelly had a gallery. But the earliest was Helen Gee's coffee shop/gallery called Limelight in Greenwich Village. She exhibited and sold prints by Ansel Adams, Bernice Abbott, Robert Frank for $50.00. After Stieglitz and 291 in the 20’s and 30’s there were, as far as I know, no photo galleries until Gee’s Limelight. The return to photography was largely due to Witkin. But that was influenced by Siembab and Boston. There were people buying from Siembab who started going to NY and buying the same image for more money. Because it was more chic to go to NY.

CG Let’s talk about Siembab. He was known to be grumpy, as I learned first hand. He was famous for charging a fee to look at your portfolio.

CC (Laughing) As I have said, there was no serious collector money. It was a gallery that showed painting, sculpture and printmaking. It’s all in the catalogue for the ICA Siembab show. Siembab was an artist but gave it up. I have one of his woodcut boards. There was a gradual move in Boston to show photography on a regular basis.

When I was at BU as a graduate student studying journalism in 1957, with a teaching assistantship in photojournalism, I became friends with Siembab and others in the art community. Newbury Street (where the Siembab Gallery was located) was the center of Boston’s art community at that time. The photojournalism professor I assisted had a huge office. I said why don’t we make a gallery out of some of this space? He agreed. The first show I put up was Nathan Lyons (1930-1916). Then I showed others, including Minor and Paul Caponigro (born 1932). That was 1957-1959. Unfortunately, within months of graduating I was drafted into the Army.

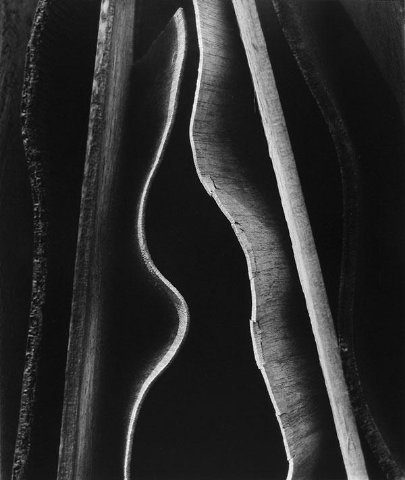

CG How did you end up as a formalist, abstract photographer?

CC Abstraction influenced my personal work from the mid-1950s; but for a living I was a photojournalist, but not for very long because of so soon being drafted. My last photojournalist job was photographing the roof of Somerville High School. I had to be in a crane over the roof. I have vertigo and I was having one heck of a time up there. I decided it was not for me. I did do a photojournalistic article for Editor and Publisher about my dissertation which was a picture story about Boston City Hospital. I also did others; one on the Lafayette Seminary in Ipswich, Massachusetts; another on a Rochester railroad yard.

CG How many books have you published?

CC Seven. Six are about my work. Siskind is the only book I wrote about somebody else. It’s called Aaron Siskind: Pleasures and Terrors. The title is based on a series of images he made. It also, for me, relates to his life, which was full of pleasures and terrors. I have written many articles and book reviews for a variety of journals throughout my life.

CG When you did your dissertation how much time did you spend with him?

CC Endless. I spent most of a summer with him on the Vineyard. I spent a lot of time with him in Chicago when he was teaching there at the Institute of Design. On and off probably a year or more. We photographed together in Kentucky in 1970!

CG Do you own work by him?

CC Until I did the book I didn’t own a lot. I now have many works we used for reproduction which he insisted on giving to me. I’m not yet sure what I will do with them. Probably I will give them to a museum but I haven’t decided yet. He was a generous guy and gave many pictures away. That’s one reason why his prices are still terrible.

CG Gus and Arlette Kayafas have a lot of his work some of which was donated to the DeCordova Museum. Arlette told me that Siskind allowed her son to choose some work.

CC Gus made large prints for him; and work may have been a part of the payment.

CG We also saw a selection they donated to the Fitchburg Museum.

CC Peter Laytin has been on that museum's board for many years. He can probably tell you about that. He has been teaching at Fitchburg State since he left MIT.

CG The Photographic Resource Center started at BU.

CC The major person behind that was Chris Enos. Alan Coleman was also instrumental in its formation. He has been writing about photography since the 1960s. He wrote for the NY Times and the Village Voice and has published several books. He helped Chris get it together. I was also involved and got its space at Boston University.

CG It was in the basement of Morse Chapel.

CC It moved on campus a few times, but first had a space in the art school. Then it was in the BU building near Kenmore Square. Later it moved across the street from the art school to an independent space. It moved several times. Now it’s at Lesley College.

CG Was the move away from BU under Silber?

CC No. It was more recent.

CG Did you get along with (John) Silber?

(Silber, [1926 to 2012], was BU president 1971 to 1996. He ran as a Democrat for Governor of Massachusetts in 1990 losing to Republican William Weld by 38,000 votes.)

CC How much time have you got? I was up for tenure and everyone approved it up through the Dean. Then it just sat in Silber’s office for a year. I inquired about what was going on, but he never responded. Eventually I got a call and his secretary said “John Silber will see you now.” I went to his office, which I had never visited. I took a seat and waited for about an hour. The secretary then said he will see you now and I asked “Where is he?” She said he was on the second floor. There were four doors on the second floor. There were no names, nothing telling you where he was. There was one door slightly open. I peaked in and saw him sitting at a desk in the corner.

I tried to decide whether I should knock on the door or walk in. I crossed the threshold and while walking into the office, with my left eye I saw this huge, framed image with glass coming off the wall. It hit the floor with glass everywhere. My first reaction was to run and save the picture.

He yelled at me from his desk at the opposite side of the room “Leave it alone. Leave it alone and come here.”

I walked up to the desk and the first thing he said to me was “Why did you raise $20,000 for Harvard and not for Boston University?”

I explained that I was chairman of the museum’s photography collections committee and that Boston University didn’t have a museum. So how, I said, would I raise that money for BU?; And then I said; “If you were on the committee wouldn’t you have done the same thing?” We started yelling at each other. It went back and forth with neither one of us sitting down. He just lost it, and I did too, and yelled back. We just kept yelling back and forth, back and forth. Then finally he told me to leave.

I left, and next thing I knew he gave me tenure. It occurred to me that the only way to deal with John Silber was to be John Silber. Give back what he gave you, which most people didn’t do. I did, and got tenure.

CG Pat (Hills) describes him as her defender.

CC He certainly wasn’t for me before our tenure issues. But then, for the first year after I left BU and went to the University of Rochester I received several cards from him as if we had become friends.

George Eastman House was in Rochester, and I had many friends there. When I first got there I was initially confused. Amazingly the dean put up with me that first semester as I pulled myself together. I taught in Rochester from 1986 to 1999 when I had a heart attack and a quintuple bypass so I decided to retire. That’s when the truck came from Harvard and took my stuff.

CG How are you doing?

CC Pretty good. Ten years ago I had an aortic valve replaced. Four years ago I had prostate radiation. You know, stuff happens. I’m still here and still working.

CG Give me a sense of your oeuvre. How much stuff have you made?

CC Oh Lord, I don’t know. I started making photographs in the late 1940s. I’ve made photographs ever since except during most of the time when I was in the Army.

CG How much time do you now spend in the studio?

CC Unless I’m involved with other things I’m there three or four days a week. It’s my life. It’s what I do.

CG Are you a successful artist?

CC If you look at my website you will see that I have been very successful in every way except financially. There were some good years when I sold work to collectors and museums. For a while I had four galleries in New York, Los Angeles and Boston and somewhere else. A few years ago, largely because of the art market’s increasing changes, I requested the return of my work from all of the galleries. One however didn’t send the work back. It was my New York gallery, the Alan Klotz Gallery; and I can’t get him to send it back. I just don’t want to deal with galleries anymore. But Alan is a good friend.

CG What were other Boston photo galleries after Siembab?

CC Brent Sikkema, now Sikkema Jenkins in New York, opened in Boston; followed by Robert Klein who had originated as a partner with Sikkema. Klein represented me for many years.

CG There was also Kiva Gallery. Howard Yezerski showed John Coplans (1920-2003). Initially he invested in that artist, including a special dinner at the gallery. But there was no response. Now the work of Coplans is widely collected.

Thanks for being a mentor and friend. When things got rough at BU you were always there for me.

CC Thank you.