The Gospel of Franklin at Steppenwolf

Playwright Aaron Carter Tackles Fathers and Sons

By: Susan Hall - Aug 11, 2013

The Gospel of Franklin

by Aaron Carter

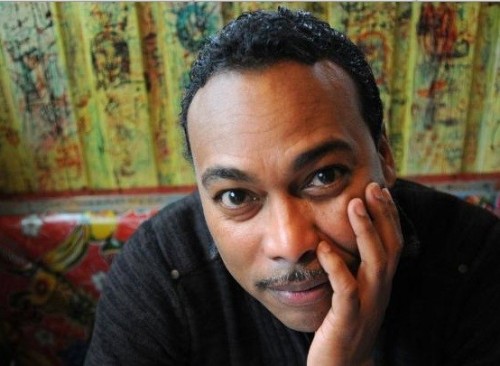

Directed by Robert O’Hara

Dramaturgy Erik Ramsey

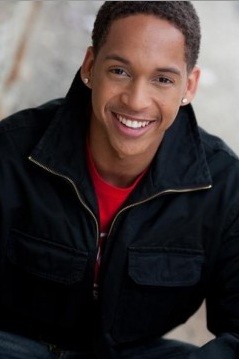

Cast: Rob Fenton (Ben), Tim Frank (Jesse), Keith D. Gallagher (Ralph), Gavin Lawrence (Franklin), Julian Parker (William).

First Look Repertory of New York

Steppenwolf

Chicago, Illinois

August 11, 2013 through August 25

Gospel is about good news and glad tidings. Aaron Carter’s fascinating play presented by Steppenwolf’s First Look program at first blush appears to be good news. But quickly, we see that it is complicated.

There are two characters who bear tidings, Franklin the father, and his son William. William is trying to piece together his own life and at the same time discover his father, not as a story, but as the truth woven from bits and pieces of information he has received over time. They are not in chronological order, but in the order of his discovery. A mosaic rather than a line.

The most intractable problems in our country reside in these characters: an undeveloped, often absent black father and his son.

William is brilliantly modulated by Julian Parker, at times insistent, at others lost, and slowly emerging as a man. Franklin’s character may be full of surprises for the son, but he is at the center, strong, resilient, a survivor. Gavin Lawrence holds us in his grip with his expressive dynamics. He seems to feel what the Gospel says: "The Spirit of the Lord God is upon Me, because the Lord has anointed Me to preach good tidings to the meek, He has sent Me to bind up the broken hearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives, and the opening of the prison to them that are bound.” Gavin helps suffering fellow workers at the factory.

The forces that collide in Carter’s play make you sit up. Most often in the real world, the father is in prison. This present father/pastor reminds ceaselessly of God’s role. He shows us how convenient it is to call upon a higher power to solve problems. God is not in the quotidian, and mere mention of his name gives a false relief.

While Franklin calls upon New Testament images, the son discovers that his father’s Gospel is whatever crosses his mind in the moment. God is a jumping off point for improvisation. The Big Book lies around the house, and is given as a gift. One character tries to absorb its wisdom by stepping on it.

Both father and son flirt with bisexuality, the father seems to be more gay than straight. Direction by Robert O’Hara provides some startling and touching turns. The father, teaching his thirteen-year-old son to kiss his mother now that he is a man, puts a stool between them so that the private parts are a least a foot apart. A spider hug not a bear's.

Touching on broader themes of the church’s place in curing the problems of sexual orientation, the three characters Franklin tries to convert to God are all gay and the objects of his desire. Rob Fenton, Tim Frank and Keith D. Gallagher each are tucked into this role over time, but each brings a different and original twist: One suffers from the suicide of a brother, another from an unfortunate marriage, and the third from the discovery that he is gay. He wins when his addictive impulses are lifted with that admission.

In the black community, there is more stigma attached to being gay, perhaps because men have had so many problems becoming men. Carter elected to have all the objects of Franklin’s desire be white men. Differences may attract, but clearly foreigners keep some truths at bay, even when Franklin is in their midst.

Carter's complex brew mixes familiar factors into fresh insights. In The Gospel of Franklin, these issues are all dramatized effectively. The swirl of paternity, homosexuality, education, marriage, money are all part of the story. Echoes of Penn State and the Catholic Church are everywhere in this African American home, but it is clearly African American. That a black father is trying to father his son is a heartening message from an African American playwright.

One scene was repeated twice, a reenactment of the Maundy Thursday ceremony in which Christ washed his disciples feet. Once, in St. Thomas Church on Fifth Avenue in New York, Bishop Walter Dennis, a black man, performed this ritual during the Easter sequence of services. One small white boy, whose socks had not been changed for three days, sat up near the altar and poor Bishop Dennis, amidst the rising stench, went about the ritual washing. What a lesson in humility.

What does this ritual mean to Carter? Perhaps, for all his pontificating and calling out to God, Franklin, like Christ, is a humble man, who would kneel before the men he is trying to ‘cure,’ including his own son. Like all relationships between healers and lost sheep, Franklin is demonstrating his humility.

Seeing performances in the Garage theater of about 100 seats where Steppenwolf introduces work to the world, turns out to be revelation. Such power and drama are rarely seen on larger stages. Except, of course, at Steppenwolf.