Hamlet Opera in Oakland

West Edge Opera at the Pacific Pipe Warehouse

By: Victor Cordell - Aug 11, 2017

“Then I discovered that being related is no guarantee of love.” Stieg Larson from The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

The highly innovative West Edge Opera opened its 2017 Festival at its new home – the Pacific Pipe Warehouse in Oakland, a cavernous and brawny industrial structure of metal sheets, beams, and pipes. The setting couldn’t be a sharper contrast with the traditional environs of grand opera, but typical of what West Edge undertakes, it works well.

Even when dipping into the heartland of the romantic era of opera, West Edge can be expected to offer an off-center selection. For the opening, it serves up a French language Hamlet, composed in 1868 by Ambroise Thomas, with libretto by Michel Carré and Jules Barbier. The staging of this production is striking, and cast and orchestra perform well in this interesting, yet oft-criticized treatment of perhaps the most anointed theatrical piece in history.

Ambroise Thomas embraced the melodic tradition. The music in Hamlet matches the libretto well and pleases the ear throughout, yet it lacks tuneful memorability associated with opera from its period. Strains of Gounod can be heard but without culmination. The tessitura is somewhat lower than expected because, despite the fact that Hamlet is the central figure and a young man, the part is written for a baritone rather than a tenor. Edward Nelson sings Hamlet with fine voice and affect.

Only after intermission (starting with Act 3) do the music and plot line rise to heighten dramatic tension. At that point, a powerful succession of set pieces lifts the opera. Of course, everyone anticipates the “To be or not to be” soliloquy, but vocal gymnastics start afterward with a trio among Hamlet, Ophélie, and Gertrude in which Hamlet admits that he will not marry Ophélie and advises her to “get thee to a nunnery.” In the following confrontation between Hamlet and Gertrude, the esteemed Susanne Mentzer transposes her normally warm mezzo tone to dramatic characteristics with fine effect.

But the fireworks arise in perhaps the most significant piece from the work, Ophélie’s mad scene. Here, shimmering soprano Emma McNairy adeptly raises her voice to the harsh screech necessary as she prepares to drown herself. The staging of this scene is stunning. In low light, Ophélie’s dress appears to be toga-like, dark blue and pleated on the bias. However, a phalanx of men unwrap the dress from the hem by lifting it and walking in circles. The dress becomes a translucent trampoline-like membrane, under which men struggle to escape before Ophélie herself disappears beneath the blue. A truly striking representation.

Conductor Jonathan Khuner manages dynamics and tempi well and coaxes a mellow sound from about 25 instruments which balances well with the singers. This orchestra cannot match the sound of the full orchestration for a grand opera, but it more than satisfies. Acoustics are okay for a facility that is clearly not designed for this use, but they seem a little weak when singers face the more open house-left side. On opening night only (one hopes), a rumbling noise from elsewhere in the facility intruded. Though distracting to the audience, performers did not have to strain to overcome it. It turns out that the company was unaware that a Burning Man event had been scheduled elsewhere in the facility.

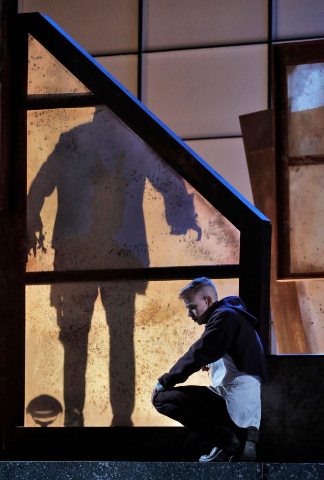

Staging is simple overall but highly effective, dominated by light-colored, framed panels that are vertically layered and akimbo. Lighting is predominately low and harsh with a striking noirish look. It works well, though there are some sequences with white back lights that face the audience and create a visual disturbance.

Much of the criticism of this work is noteworthy but inappropriate. Complainers argue that the opera misses much of the play, which must be expected unless you want a five-hour opera. This is the same argument people use when they’ve read a long book and then see the movie. However, if you know what’s missing, you can fill in the pieces. If you don’t know the source material, then you don’t know what you’re missing. Solution – if you can’t deal with that, don’t go to the opera.

Another criticism is that the role of Ophélie is too large and overpowers Hamlet’s. Composers are sensitive to range balancing, and with only two female characters, it makes sense to have the higher range represented. Besides, after being inspired to write a striking mad scene, what would you do? Delete it?

Hamlet, composed by Ambroise Thomas, libretto by Michel Carré and Jules Barbier, based on the Alexandre Dumas père’s adaptation of William Shakespeare’s play is produced by West Edge Opera and plays at the Pacific Pipe Warehouse

Posted by Victor Cordell and For All Events.