Avedon Fashion 1944-2000 at the MFA

All Models, No Portraits, 5 Decades!

By: Shawn Hill - Aug 12, 2010

Avedon Fashion 1944-2000

August 10, 2010—January 17, 2011

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

www.mfa.org

Years ago, near the beginning of Malcolm Rogers' tenure as director of the Museum of Fine Arts, I reviewed a huge Herb Ritts retrospective and wasn't very impressed. It seemed to be about celebrity and popularity more than about art, and felt like a suspect move considering the MFA we knew up to that point.

Then I noticed that the public arguments about the "controversial" show didn't center on artistic merit or the spectre of a commercial photographer (an oxymoron if there ever was one, or at least a redundancy), but were mostly about the "shocking" display of so much nudity in such a venerable Boston institution. I should have thrown up my hands right then.

Now, of course, the MFA is well on its way to embracing popular taste (and providing an historical context when it can) and there is an Herb Ritts Gallery in the Museum itself (a fitting and generous memorial, it's currently housing the very worthy work of documentary photographer Nicholas Nixon), and a show about Richard Avedon comes not as a shock, but as a near necessity. It's not just the courting of the Boston fashion world that the MFA is planning as "Fashion Fall" with events, speakers and other artists that makes an Avedon show special. It's the serious value of the work itself, a testament not just to the whims of fashion, but to something much more important: style, and its truth-telling evolution through the troubled history of the 20th century.

The curators make a strong case for the significance of near neophyte photographer Richard Avedon in Paris in the 1940s and '50s, lauding him for using unusual, striking models (some even Asian or black, most American) to create a Parisian scene of opulence and grandeur in the face of the reality of the time: depression, Occupation, and the lingering scars of a second World War.

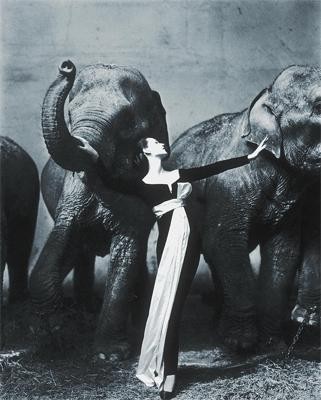

Avedon's images of Suzy Parker (a redhead with freckles she doesn't let show until the 1960s), Sunny Harnett, Dovima, and (mostly as another prop for the ladies) male models like Robin Tattersall don't just record a Parisian center of pomp and circumstance. They're creating it, before our eyes, and the City of Lights seems grateful for these exotic new stars.

The show is chronological, and moves on to the more casual, experimental and frankly strange looks of Mod London and in the 1960s with transparent ease. Avedon is clearly inspired by the fashions of Carnaby Street, by intriguing divas like Veruschka (who starred in the seminal fashion photography film Blow-Up), waifs like Penelope Tree and Twiggy, and non-white beauties like Donyale Luna and China Macado.

In fact, the show moves further, as Avedon's career extended into the 1990s, with images of Lauren Hutton smoking a joint; a fashion spread in the New Yorker melding Surrealism to the idea of the Vanitas; in general coping with the collision of the Sexual Revolution and the Me Decade. But they almost needn't have bothered, as there isn't a more modern image in the entire show than Avedon's 1959 portrait of Brigitte Bardot.

The French siren stares back at us, a Dietrich-like face of nearly skeletal shadows. She has caverns for eyes, carved cheeks, and full pouting lips in near-perfect symmetry. Cascades of blonde hair frame her face, falling to where her shoulders would be, curling luxuriously and blown fully into a leonine mane of sensuality. The contrast is so blown out that we can't see the texture of her skin, not much more really than that maze of hair and the Nefertiti-esque proportions of her facial features. Fifty years ago or yesterday, such a photo would look just the same. And that's what defines style: completely contemporary timelessness.

There are many other great works, including the signature image of "Dovima among the Elephants" from 1955 which captures some perfect tension between refined elegance and wild animal exuberance. The curators have augmented the show with looks behind the scenes at actual working prints from some of his earliest magazine assignments, and a theatrical room of darkened walls and spotlit images meant to evoke how Avedon revived glamour in a shell-shocked world.

But you really need none of this trickery, and it's not in perfect congruence with the minimal, dynamic lines and geometric shapes that define Avedon's best work in fashion. One of his innovations was to capture movement in dresses that had often been presented so statically. His 1960s muses dance across the walls like a troupe of ballerinas, making unlikely materials like tweed and wool knits sexy and fluid and expressive.

What the show leaves out are Avedon's impressive portraits, and most of the more editorial work that occupied his output in his mature years. That work has its own shows and catalogs. With this show we're in the black and white world of high drama and high fashion, and, as with all of the best in taste, nothing more is needed.