Robert Henriquez in North Adams Exhibition

Haiti Galerie Part of Summer Long Down Street

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 12, 2010

During the Spring semester the North Adams based Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts organized a celebration of the arts and culture of earthquake devastated Haiti. The Pittsfield based artist, Robert Henriquez, gave a slide presentation of five of the masters of Haitian contemporary art.

Continuing its commitment to a wider understanding of the culture of Haiti the summer long DownStreet project in North Adams includes Galerie Haiti on Main Street. It is next to MCLA’s Gallery 51.

Although not widely known in the Berkshires the work of the Haitian masters which Henriquez presented commands six or seven figures and is sought by collectors and museums. The Nader Collection was severely damaged by the earthquake. It is estimated to have a value of between 30 and 100 million dollars. UNESCO assigned a special envoy to estimate the damge to the collection.

“We are not talking about tourist stuff” he said when we met in Galerie Haiti to view his work in a group exhibition Reimagining Haiti. “This is not the kind of work which you can pick up for a few dollars. But major masters.”

There is what he calls “A lexicon of imagery and style used in the work of Haitian artists. There is the juxtaposition of unusual components. The elements dissolve into a narrative. Starting in the 1940s and 1950s there was the movement of Prise de Conscience. It was focused on taking stock of Haiti. Even (the dictator) Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier (died in 1971) was a part of that. In the schools there was an emphasis on the history, literature, art and culture of Haiti. I was brought up in that and studied art at Centre d’art.

“The five artists I presented at MCLA reflect that tradition. Philome Obin (1892-1986), in the canon is like Henri Rousseau. He is called a sophisticated naif. He is in the school of the beauty of the naive. Today those works are priceless. Bernard Sejourne (1947-1994) instead of the poverty and ugliness was interested in conveying the beauty of Haiti. He was the most famous member of the 'School of Beauty.' Wilson Bigaud (Born 1931) Prefete Duffaut (Born 1923) and Jacques Enguerrand Gourgue (1930-1996) depicted indigenous subjects. They were my heroes.”

In particular he speaks of his friend Sejourne who died young of AIDS. “I would spend the day with him in the studio while he painted. He would be wearing a leopard skin thong. He had a wild streak. When he came to the US he would stay with me from time to time. Because so many Haitians died of AIDS back then people thought that’s where the disease came from. I had a lot of fights about that when I was with CBS.”

For 23 years Henriquez worked at CBS. Through family connections he started in the mail room. When he left in 1991 he was Associate Producer of Live Broadcasts for the Cultural and Religious Unit. This took him all over the world for example broadcasting the Christmas Eve mass celebrated by the Pope in Saint Peter’s. In an administrative decision the unit was canceled.

But for many years it gave Henriquez a global reach that informs his eclectic approach to art and culture. For a young man of his social and economic class he should have been educated in France. But because of the regime of the Duvaliers he came to the US speaking very little English. With his accent and cute looks he says that he prospered in the CBS Mail Room. He recalled when he was called in by the brass and told he would have to trim his Afro and change his duds as he was being groomed to move on up to the big league. It was a change he welcomed.

But what was it like to come up through the ranks in the whitebread world of network broadcasting? He talks of attending social events in the Berkshires and looking around and “I am the only one.” He describes with great irony and humor being a “Fly in the Buttermilk.” This is the title of Greg Tate’s book on the artist Jean Michel Basquiat.

Robert recalled playing tennis with Jean Michel’s father who was Haitian. His mother was Puerto Rican. “I met Jean Michel a few times but he traveled in different circles. He made it big in the white New York art world and was friends with Warhol, who was a kind of a god father. There was a famous art world battle with Julian Schnabel (who made a successful film on Basquiat). Jean Michel was interested in just three things: Art, fame and drugs.”

Basquiat was a high school drop out and self taught artist. For Henriquez his style reflected a Haitian lexicon, although the images were of Miles Davis, cartoons, and boxers. With the tag of a crown and Samo he was a part of the graffiti movement. When those artists were organized in a major exhibition at P.S.1 he shot to overnight fame. The paintings which sold for $400 on opening night at the museum climbed to $40,000 each in a matter of months.

“On opening night the Swiss dealer Bruno Bishofberger showed up with a fur coat and a blonde on each arm. He looked around and said ‘Where is the work of Basquiat?’ The word was already out. That night he bought three paintings for $1,200” Henriquez recalled.

Of course there are challenges of not living in one’s own social and racial milieu but Henriquez explained that it is a family tradition. He discussed his grandfather who introduced soccer to Haiti.

Constantin Henriquez de Zubiera was an Haitian born French rugby union footballer. He played as number eight, wing and centre. He played at Olympique de Paris and Stade Français. He won as a Stade Français player the titles of French Champion, in 1897, 1898 and 1901. He was the first person of African origin to compete in the Olympic Games and by extension the first to become a Olympic gold medallist. He was a member of the French squad that defeated England and won the Olympic title at the first Rugby Olympic Tournament. He also won the silver in the tug of war at the 1900 Summer Olympics.

“The schools in Haiti were terrible back then” he said. “So wealthy families sent their children to France for an education. My grandfather was one of three guys who came back and brought soccer with them. It became the national sport. He scored the first goal in Haiti.”

In contemporary critical theory there is the philosophical development of Créolité. It contrasts with the movement that preceded it, la négritude, a literary movement spearheaded by Aimé Césaire, Léopold Sédar Senghor and Léon Damas in the 1930s. The Négritude writers sought to define themselves in terms of their cultural, racial, and historical ties to the African continent as a rejection of French colonial political hegemony and of French cultural, intellectual, racial, and moral domination. Césaire and his contemporaries considered the shared black heritage of members of the African diaspora as a source of power and self-worth for those oppressed by physical and psychological violence of the colonial project.

The Martinican Edouard Glissant rejected the monolithic view of "blackness" portrayed in the négritude movement. In the early 1980s, Glissant advanced the concept of Antillanité ("Caribbeanness") which claimed that Caribbean identity could not be described solely in terms of African descent. Caribbean identity came not only from the heritage of ex-slaves, but was equally influenced by indigenous Caribbeans, European colonialists, East Indian and Chinese coolies (indentured servants). Glissant and adherents to the subsequent créolité movement (called créolistes) stress the unique historical and cultural roots of the Caribbean region while still rejecting French dominance in the French Caribbean.

“That’s exactly what I mean was going on in the culture of Haiti when I was growing up” he said. “We read all those guys.”

Speaking of his own family Robert discussed that it can be traced to Spain when they were Sephardic Jews. During the Spanish Inquisition they became conversos. So he was brought up Catholic. But over the years of our friendship he has often discussed the power and importance of Vodou which in New Orleans is known as Voodoo. It is precisely what brought revolution and independence to the island defeating the army of Napoleon.

Henriquez describes Vodou as a pure African religion. The patois of Creole developed out of the disparate Africans from many tribes with different languages finding a way to speak with each other.

When he arrived in New York as a young man he was trained and aspired to be an artist. As is the norm it became complicated. There were the issues of survival and a career that flourished in broadcasting. So making work simmered on the back burner.

By the time he returned to the studio he was deeply influenced by the contemporary New York art world and MoMA. For a time he pursued minimalist painting as the purest expression of creativity. He describes that period, which survives in slides, as a synthesis of the influences of Barnet Newman and Ad Reinhardt.

“When I brought slides to galleries I was rejected by the twenty something receptionists” he said. How many of us have had that experience. “They told me we don’t show that kind of work.”

The epiphany occurred during a Reinhardt retrospective at MoMA. “I went once a week to see the show. I would stand and study the works as people just walked by. Finally on the twelfth visit it came to me. I was in the final room of the black paintings. You have to really concentrate to start to see them. It finally hit me. This is the end. This is the death of painting as we know it.”

What started from that moment was a mandate to return to socially engaged art and to use all of the resources of Western Art as an indictment of the culture. “I use all of the techniques of the masters, chiaroscuro, rendering, perspective, and the techniques of the masters to deconstruct the master’s house.”

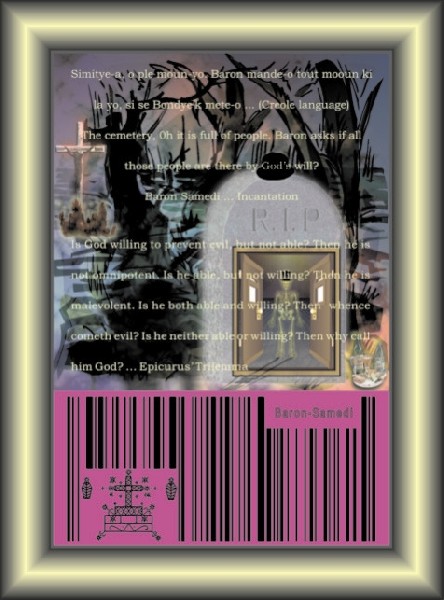

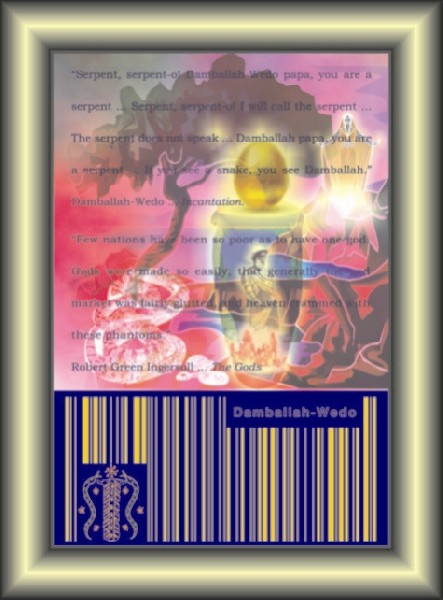

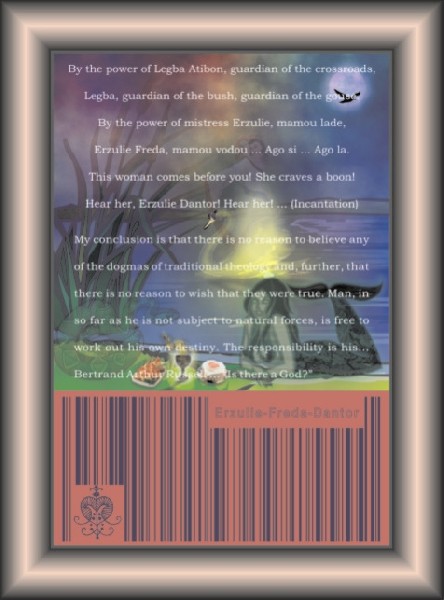

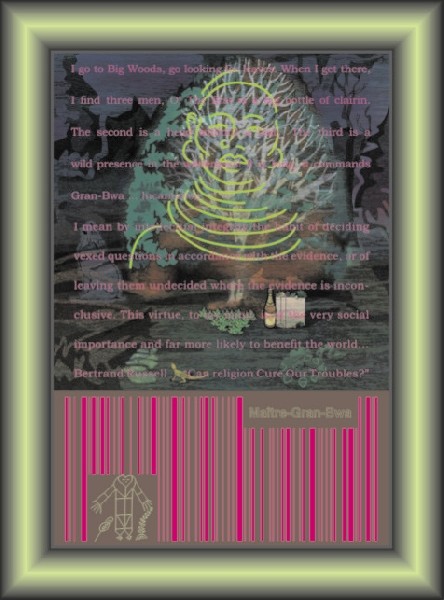

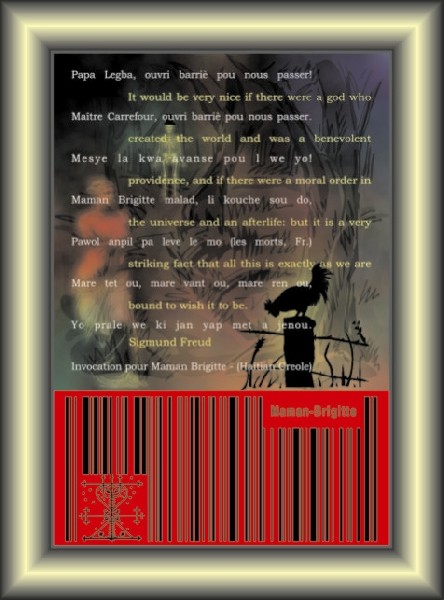

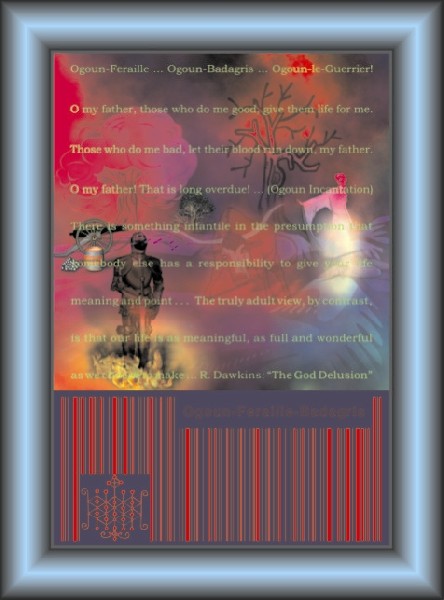

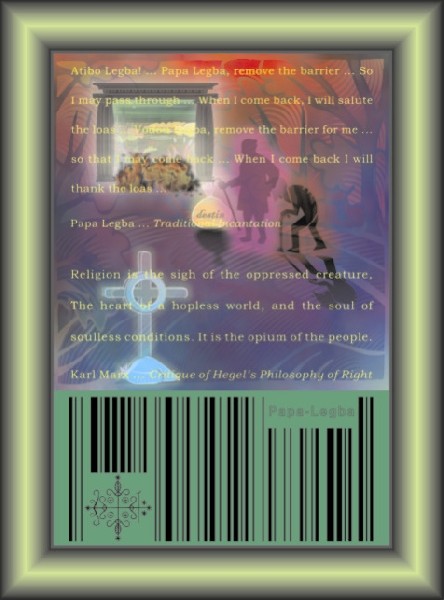

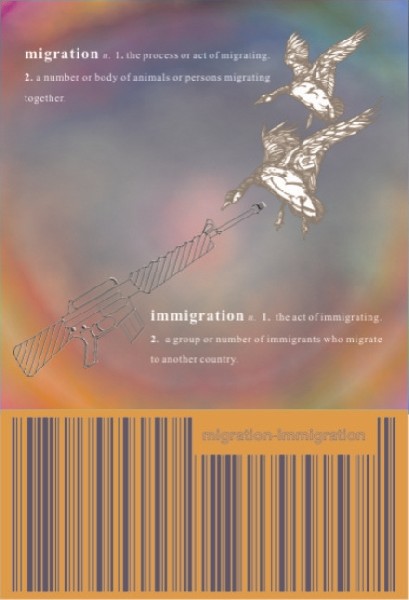

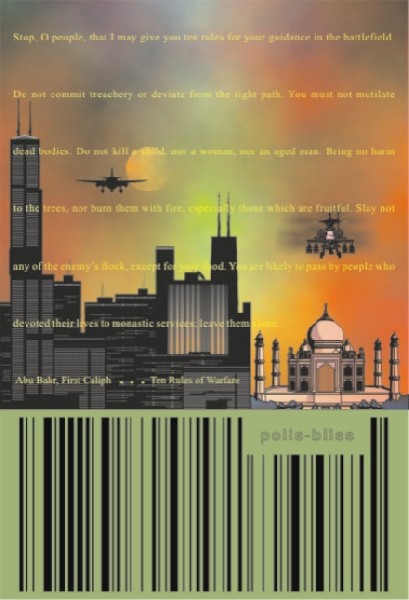

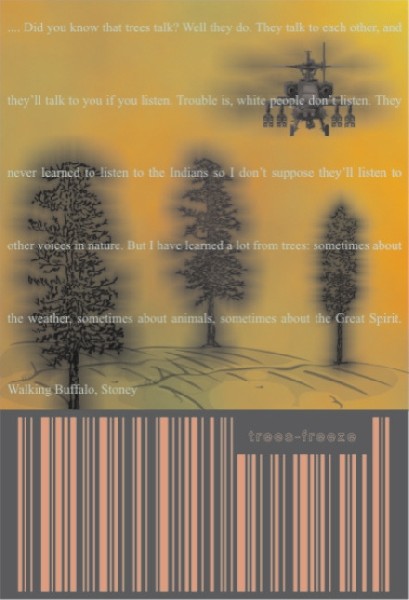

We stood in front of the seven images of the Haiti series “Seven Loa of Vilokan” of digital, 13 x 19” prints. It has taken several years to learn to build them as digital files.

Don’t expect me to explain as it is technically that complicated. “It is all there” he said. “The minimalism of Reinhardt but with the bar code of Warhol. The first impression is that they are bright and colorful. Eye candy. But then you come closer and see the images and text. The idea of using text came to me when I visited a Barbara Kruger show at Mary Boone.”

If you look carefully at the prints you will find that lines in Creole are interspersed with quotes from Western thinkers like Hegel and Freud. Of course most viewers are unable to read or understand the Creole. But we contemplate what the lines have to do with the more readily familiar Western thinkers.

The work is not about providing answers. Robert has discussed it with me but I would never presume to state that I understand it. Its richness of associations, sharpness of indictment, and scope of vision is beyond my grasp. The most I can venture is being provoked and engaged. It is art meant to be experienced and felt.

“It is not up to me to explain it” he said. “My job is to create it. It has taken more than six months to create these seven images. The last was finished just before the installation. Whether the viewer responds is not up to me. But this work is all about Haiti.”

Artist’s Statement

“What I think I have in common with the school of deconstruction is the mode of negative thinking or negative awareness, in the technical, philosophical sense of the negative, but which comes to me through negative theology.” — Harold Bloom

At the very start of working on my new series, “7 Loa of Vilokan”, I realized that I could only envision—not create—situations that would address the theological question of the Loa’s existence as Mystères, or ancestral deities in the Vodou religion. I posit that envisioning the “existence”, “immanence” and “presence” of the Loa in Vilokan does not fit in the empirical framework of physical existence. Vilokan, being the home of the Loa in Haitian Vodou, is synonymous with the spirit realm, as opposed to the physical realm in which mortals live. This alternate plane of existence is often depicted in Haitian paintings as “le comté de l'imaginaire”, or county of the imaginary. It is not the equivalent of some mythological place, but a realm fundamental to the make-up of a very different cosmology. Conceptually, the whole endeavor is an impression in the eyes and mind of people who inhabit the physical world. I want to show this otherworld in non-physical forms, as a realm similar in many ways to the physical world, but everything is somehow grander, stranger, more perfect … a cosmological “otherness”.

This purpose in my new series is to imagine the edges of a space between the magical and the real, and develop an aesthetic stratagem that could reveal an untold visual possibility. For me to find this edge in "Reimagining Haiti" is to delve freely into a zone of magical realism to explore the bright life-affirming side of Haitian art. From this privileged position, I can utilize ironic distance to juxtapose visions of the Fantastic and the reality of continual political upheaval … the endless struggle for a political ideal.

For my subject matter, I draw upon Haitian art’s most storied Vodou themes; decontextualize the reflected content by removing metaphysics and theology, then mainline blasphemy. This visual situation is a strange enterprise, since blasphemy, in this case, is not apostasy but a form of visual irony about contradictions that do not resolve into larger wholes, juxtaposing incompatible things together because all are necessary and true. This brand of irony is to engage in very serious play that challenges the status quo by interpreting contradictory existential orthodoxies in a deconstructive process. In the sad case of Haiti, “Reimagining Haiti” can ultimately expose the country’s internecine strife as out of tune with the First World, which, ironically, is partly responsible for this sorry state.

J.M. Robert Henriquez

Reflection on “Reimagining Haiti”

July 2010

(Dedicated to the memory of Ariana Magnifico)

Notes on Vodou by the artist

Haitian Vodou (Also spelled Vaudou) traces its roots to the West African Vodun of the Fon nation or Dahomey presently known as the Republic of Benin. This particular version of Vodou was carried over by Africans who were forced into slavery in the New World and Haiti in the 16th century. They still followed their traditional African beliefs, but were forced to convert to the religion of their slavers—Roman Catholic Christianity. To ensure its survival, the practitioners of Vodou, commonly described as Vodouisants, cleverly syncretised their sacred beliefs with Catholicism. The core belief in Haitian Vodou is that minor deities called Loa (pronounced Lwa) are subordinates to the one and only God—the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob—called Bondyè (from the French Bon Dieu). This Supreme Being does not intercede in human affairs, and it is to the Lwa, whose essence and presence are syncretised with Roman Catholic Saints, that Vodou worship is directed. Loa are the spirits or deities of the Vodou religion practiced in Haiti, Benin, and other parts of the world. They are also referred to as Mystères. They are divided into three main families, Rada, Petro, and Guédé. Loa can be viewed as forces of nature, but they also have personalities and personal mythologies. They are intermediaries between God the Creator—who is distant from the world—and humanity. The word "Loa" has but one form for singular and plural.

Haitian Creole or Kréyol, which is spoken by virtually the entire population of Haiti, is mostly made up of French and Spanish, as well as influence from West Africa and indigenous Taíno cultures. The creation of the Kréyol language and the common practice of Vodou were seminal in the only successful slave revolt that would give birth to the Republic of Haiti.

Regarding the importance of Vodou in the Haitian Revolution, an according to the official "History of Haiti and the Haitian Revolution"[2], in 1791 the following events occurred:

“A man named Boukman, another houngan, organized on August 14, 1791, a meeting with the slaves in the mountains of the North. This meeting took the form of a Vodou ceremony in the Bois Caiman in the northern mountains of the island. It was raining and the sky was raging with clouds; the slaves then started confessing their resentment of their condition. A woman started dancing languorously in the crowd, taken by the spirits of the Loa. With a knife in her hand, she cut the throat of a pig and distributed the blood to all the participants of the meeting who swore to kill all the whites on the island. On August 22, 1791, the blacks of the North entered into a rebellion, killing all the whites they met and setting the plantations of the colony on fire. However, the French quickly captured the leader of the slaves, Boukman, and beheaded him, bringing the rebellion under control. The death of Boukman although it had temporarily stopped the rebellion of the North failed to restrain the rest of the blacks from revolting against their condition. The Revolution that would give birth to the Republic of Haiti was under way and nothing could stop it.” … The ceremony was first documented in 1814 by Antoine Dalmas in his book History of the Saint-Domingue Revolution

Vodou Terms and Definitions

Haitian Vodou: (Also spelled Vaudou) is a syncretic religion combining native African religion, particularly the religion of the Dahomey region of Africa (the modern day nation of Benin) and Roman Catholicism.

Vilokan: is the abode of the Loa in Haitian Vodou … is synonymous with the spirit realm, as opposed to the physical realm in which mortals live.

Loa: are the spirits or deities of the Vodou religion practiced in Haiti, Benin, and other parts of the world. They are also referred to as Mystères. They are divided into three main families, Rada, Petro, and Guédé. Loa can be viewed as forces of nature, but they also have personalities and personal mythologies. They are intermediaries between God the Creator—who is distant from the world—and humanity. The word "Loa" has but one form for singular and plural.

Vévés: are symbolic designs used in ritual, drawn on the ground with cornmeal prior to or during a Voodoo ceremony. These designs represent the various powers and attributes of the Loa to be invoked, and serve as a focal point for invocation and offerings.

Damballah-Wedo: is one of the most revered of the African deities, the Loa of peace and purity, and the one who grants riches and sustains the world. He is both a member of the Rada family and a Racine (or root) Loa. He is depicted as a serpent and is closely associated with snakes. He is considered the father of all the rest of the loa and—along with his wife Ayida Wedo—to be the Loa of creation … the Loa of new life, transformation, and fertility. He has other aspects, one of which is “Damballah le Flambeau“, where he appears in fire form.

Papa-Legba: of the Rada family is the gatekeeper to the spirit world, Vilokan. Legba is always the first and last spirit invoked in any Vodou ceremony, because his permission is needed for any communication between mortals and the loa—he opens and closes the doorway. Legba is also strongly associated with the sun and is seen as a life-giver, the distributor of fate, transferring the power of Bondye (or God the Creator) to the material world and all that lives within it. This further strengthens his role as the bridge between realms.

Erzulie-Freda-Dantor: in her Rada family aspect as Freda, she is the light skinned spirit of love, beauty, jewelry, dancing, and luxury. In her Petro family aspect as Dantor, she is a warrior with darker skin, and a particularly fierce protector of women and children.

Ogoun-Feraille-Badagris: is a descendent of a military line of the Petro family of Loa. He was originally associated with fire, blacksmithing and metalworking. His focus has transformed over the years to include power, warriors, and politics. His dual aspect Feraille-Badagris represents the quintessential Warrior-Diplomat Loa.

Baron-Samedi: is the head of the Guédé family of Loa, or an aspect of them, or possibly their spiritual father. Like his wife, the Loa Maman Brigitte, Baron Samedi is the ultimate suave and sophisticated spirit of Death - quite cultured and debonair. He has an existential philosophy about death, finding death's reason for being both humorous and absurd. He is the guardian of the underworld.

Maman-Brigitte: is a death Loa of the Guédé family, the wife of Baron Samedi. As a New World Loa, Maman Brigitte is European in origin. Rumor has it she's a descendant of a Celtic "triple goddess" of beauty, poetry, and healing, carried to Haiti in the hearts of poor indentured whites or blanc poban.

Maître-Gran-Bwa: means "Master Big Tree". As an important member of the Petro family he is the master of the forests of Vilokan, the land that is home to the Loa. He is also the master of the wilderness in general. The Mapou, or silk-cotton, tree is specifically sacred to Gran-Bwa. It is a Mapou tree that is seen as connecting the material and spirit worlds (Vilokan), which is represented in Vodou temples by a central pole known as "poto mitan."