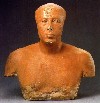

Prince Ankhaf a Coveted Treasure of the Museum of Fine Arts

Grandstanding Mohamed Saleh Demands Its Return to Egypt

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 14, 2011

The conventional wisdom regarding the great museums of the world is that they house loot acquired during the era of Colonialism and Nationalism.

It is how Lord Elgin “liberated” the sculptures of the Parthenon that continue to reside in the British Museum. Greece has built an Acropolis Museum to house them and continues to demand their return. Despite an international chorus of a moral injustice, including many British experts, the priceless masterpieces remain in Great Britain.

As reported by Geoff Edgers in the Boston Globe, Mohamed Saleh, once the director of Cairo’s Egyptian Museum and now the man in charge of the collections for a planned $550 million Grand Egyptian Museum is demanding the return of the Old Kingdom bust of Prince Ankhaf.

Through the excavations of George Andrew Reisner, the founder of the Museum of Fine Arts Department of Ancient Egyptian and Near Eastern Art, the museum has what is regarded as the finest collection of Old Kingdom art other than the works in Cairo.

Of the Ancient Egyptian art owned by the MFA the bust of Prince Ankhaf is its rarest and most unique treasure. It is on the short list, perhaps top five, of the greatest and most valued objects of the MFA. The importance of the bust to the integrity and reputation of the museum and its world class status cannot be underestimated.

In 1943 the MFA Egyptologist and curator Dows Dunham wrote that it is the “most convincing example of individualized portraiture in the Pyramid Age.’’

It may in fact be the first true portrait in Western Culture. While there are many “portraits” in Ancient Egyptian and Near Eastern art, up to and including the era of the Old Kingdom, the Ankhaf is the only true likeness. The convention was to idealize the features of a ruler or potentate. Cartouches and honorific inscriptions, rather than specific facial features, identified that individual.

The Ankhaf bust is compellingly realistic with unique bags under his eyes and a receding hairline. To make that point Dunham put a hat, shirt and tie on the Prince and photographed him in the guise of a modern man as an illustration for an article in the Museum Bulletin.

Dunham did not dress up the actual sculpture but rather a plaster replica. It had been created during World War II as a switch out on display in the museum. Because of the risk of potential bombing and destruction of the original, it and several other rarest MFA treasure, were sent to Williamstown for safe keeping. (See comments below)

Zahi Hawass, ousted with the fall of Hosni Mubarek , is known for publicity stunts, popular TV shows on National Geographic and the History Channel, as well as allegations of bribes and kickbacks, likes to stir the pot with sensational headlines and outrageous demands. The Ankhaf is on a list of top ten Egyptian antiquates which he is demanding be returned and housed in the new mega museum. Others include the Rosetta Stone in the British Museum and the stunning bust of Queen Nefertiti in Berlin.

“The Boston Museum of Fine Arts is very famous for buying stolen artifacts all the time,’’ Hawass the former Head of Egyptian Antiquites is quoted in the Globe as having stated. But he is being disingenuous.

Hawass and every Egyptologist knows full well that the MFA famously acquired the priceless treasure fair and square.

The story of its acquisition is a compelling tribute to the skill of Reisner as a Yankee horse trader.

Egypt, a poor third world nation, invited teams of archeologists to finance their own digs. It was the kind of work that Egypt lacked the resources to undertake. The ground rule was that at the end of each season the objects unearthed would be divided. Thus, at no expense, Egypt was able to create staggering collections. There was another rule that in the event of a Royal tomb all of the objects would be the property of Egypt.

In 1922, for example, when Howard Carter and his sponsor, Lord Carnarvon, found and excavated the tomb of King Tutankhamun all of that material remains in Egypt.

During the 1920s the decision was reached to excavate the area around the three Old Kingdom Pyramids of Giza. The terrain was divided into quadrants and lots were drawn between the British Museum, The Berlin Museum, The Louvre, and the MFA. The segment assigned to the Boston team surrounded the smallest of the three pyramids built for King Mycerinus. It proved to be the quadrant richest in objects a portion of which, including the slightly under life size, slate sculpture of King Mycerinus and His Queen, are the core of the MFA’s collection.

In 1925, when Reisner found the Ankhaf, realizing its importance, and that it would inevitably be selected by Egyptian inspectors in the annual division, he kept it in the shed as a trump and bargaining tool.

That opportunity presented itself in 1927. By then his team was in the midst of the incredible labor of the three-year-long task of excavating the tomb of Queen Hetepheres the mother of Mycerinus. It is speculated that her funerary objects were hastily piled into virtually an unmarked grave. Her burial may have been broken into, as was common, and fearing reprisals from the Pharoah, the objects were reburied with such haste and obscurity that they remained undetected until Reisner found them.

Much of the material in her tomb entailed carved wood furniture with a gold leaf exterior. Over millennia the wood rotted and the objects collapsed. It was a great feat of the most meticulous archaeology to document and remove the furniture. Replicas are on view in the MFA and all of the original material remains in Cairo.

In the annual division of 1927 Reisner produced the Ankhaf and appealed for it in lieu of three years of work and no objects for the MFA entailed in the Hetepheres excavation. As a gesture of good will the object was awarded to the MFA.

Yes, many objects in museums are rightly questionable. But this is not the case. The MFA acquired it legitimately. By every legal and moral standard it deserves to remain in Boston.

There have been requests to borrow the object for museum exhibitions as Saleh did in 2007. With its fragile, red tinted plaster layer over carved limestone it is deemed by conservationists to be too delicate for travel.

When the MFA, through its chief curator, Rita Freed, declined the loan Saleh countered with a campaign for its return.

"This is not a question of Egypt,’’ MFA director Malcolm Rogers is quoted by The Globe. “It’s a question of the object and its integrity. It’s a great, great treasure and we don’t want to put it at risk.’’

The repatriation of works looted by nations and stored in its museums is an ongoing process. As the result of many law suits, or internal audits of provenance, countless works of art have been returned to their nations of origin in recent decades.

The MFA is hardly innocent. It houses the only Spanish Catalan Romanesque chapel not in a museum in Barcelona. When it was looted all of the many similar chapels were stripped of their murals which are housed in a wing of a museum in Barcelona. In his History of the Museum of Fine Arts the author Walter Muir Whitehill described that as akin to closing the barn door after the cow is gone. He wrote with similar Brahmin, good old boy, panache about how Bostonians looted Japanese treasures during the 19th century.

The MFA, however, has a spotless record of continuing to loan its treasures from time to time. Actually the museum has a remarkable relationship with Japan.

So yes, there are many examples of treasures that should and one day will be returned to their nations of origin.

But Prince Ankhaf is not among them.