Edward Elgar and his World, The Bard Music Festival 2007

A broad view of the great English composer

By: Michael Miller - Aug 17, 2007

The Bard Music Festival 2007: Edward Elgar and his WorldWeekend One August 10–12, 2007

Grandeur and Intimacy in Victorian England

Friday, August 10

Program One

Elgar: From Autodidact to "Master of the King's Musick"

Sosnoff Theater

7:30 pm Preconcert Talk: Leon Botstein

8 pm Performance: Daedalus Quartet; Piers Lane, piano; Bard Festival Chamber Players; Bard Festival Chorale, James Bagwell, choral director; members of the American Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Leon Botstein, music director

Edward Elgar (1857–1934)

Sursum Corda for organ, brass, strings, Op. 11

Harmony Music No. 4

Chanson de nuit, Op. 15, No. 1

Chanson de matin, Op. 15, No. 2

Salut d'amour, Op. 12

Sevillana, Op. 7

Piano Quintet in A Minor, Op. 84

Choral Works

Saturday, August 11

Panel One

Elgar the Man and His Worlds

Olin Hall

10 am–noon

Christopher H. Gibbs, moderator; Byron Adams, Diana McVeagh, and Andrew Porter

Free and open to the public

Program Two

Music in the Era of Queen Victoria

Olin Hall

1 pm Preconcert Talk: Christina Bashford

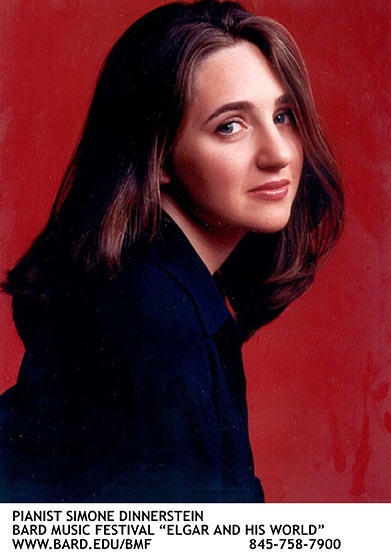

1:30 pm Performance: Daedalus Quartet; Thomas Meglioranza, baritone; Simone Dinnerstein, piano; Anna Polonsky, piano; Bard Festival Chorale, James Bagwell, choral director

Edward Elgar (1857–1934)

O Salutaris Hostia

Ave verum, Op. 2, No. 1

Ecce sacerdos magnus

Johann Baptist Cramer (1771–1858), Introduzione ed aria all'inglese, Op. 65, for piano

W. Sterndale Bennett (1816–75), Impromptu, Op. 12, No. 2, for piano; Piano Sextet, Op. 8

Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1809–47), Fantasia for piano in E Major,"The Last Rose of Summer," Op. 15

Songs and glees by T. F. Walmisley (1783–1866); John Stainer (1840–1901); C. E. Horn (1786–1849); Liza Lehmann (1862–1918); J. L. Hatton (1809–1886); and Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900)

Choral works by Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy; S. S.

Wesley (1810–76); and F. A. Gore Ouseley (1825–89)

Special Event

Pianistic Anglophilia: Elgar, Ireland, and Grainger

Olin Hall

5 pm Performance with commentary by Kenneth Hamilton

Program Three

Elgar and the "English Musical Renaissance"

Sosnoff Theater

7 pm Preconcert Talk: Byron Adams

8 pm Performance: Piers Lane, piano; American

Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Leon Botstein, music director

Edward Elgar (1857–1934)

In the South (Alassio), Op. 50

Pomp and Circumstance March No. 4, Op. 39, in G Major

Funeral March from Grania and Diarmid, Op. 42

Variations on an Original Theme ("Enigma"), Op. 36

Hubert Parry (1848–1918), Symphonic Variations

Charles Villiers Stanford (1852–1924), Concert Variations on an English Theme ("Down among the Dead Men"), for piano and orchestra, Op. 71

It is especially significant that this year's Bard Music Festival, the 18th, is the first to celebrate a British composer. The first principle of the Bard Festival is that is casts a wide intellectual net, taking into consideration not only the musical predecessors, influences, contemporaries, and so forth of a major composer, but also the broader cultural context of the composer and his music. It is difficult to argue with this premise, as an observer who comes from a background in classics and art history, I find it particularly striking how extensively and deeply the cultural connections of major composers penetrate into their society and culture as a whole. Few composers failed to set words to music, or failed to connect with the visual arts of their time, whether through the architecture of the buildings in which their works were performed, through theatrical design, or through some other association with artists. Few composers failed to read books, have opinions about religion, politics, or current events, or to play at least some small role in public life. It is astonishing how much one can pull together about the culture of a particular time and place through the biography and music of a major composer. Take for example, Bach or Beethoven, Mendelssohn or Schumann, Liszt and Wagner.

Now, after seventeen year of neglect, we have the opportunity to look at a British composer from this perspective, an Englishman, whose life spanned the late Victorian and Edwardian eras, beginning with the Indian Mutiny and ending with Hitler's takeover of Germany. Edward Elgar, like the poet Vergil in his own time, functioned as a public artist, whose public works celebrated the political and social establishment of his time, but these works are intertwined with intimately personal sentiments, private, even quirky moods, which undercut his public confidence and grandeur and make his music vital and moving today. Both the public and the private are essential to his music, and we can see his critical fortune vacillate with the English public's conception of themselves, whether in the times of Lytton and James Strachey, William Walton, Churchill, late Vaughn Williams, Auden, Britten, C. P. Snow, Graham Greene, Margaret Thatcher or Tony Blair. These diverse names suggest a shifting prospect, not unlike the Worcestershire of Elgar's earlier years, as moving clouds and changing light alter the apparent contours of the landscape. Elgar was a complex individual, a man of contradictions, if one wishes to look at it that way. The voice of imperial power, royal authority, both Anglican and Catholic faith, was a perpetual outsider, born a Roman Catholic of working class parents who had worked themselves into the lower middle class through trade, a man who lost his faith, given to self-doubt and depression, even something of a persecution complex. A composer of consummate technical ability, he always thought of himself apologetically as a self-taught musician from the provinces.

The academic and musical components of the Bard Festival, took up many of these questions last weekend and will continue to explore them over this coming weekend, not to mention a third session in late October. My experience of the festival began Saturday morning with an especially rewarding introductory panel, above all because of the maturity of the speakers and their knowledge of English music, and of Elgar in particular. Byron Adams, Professor of Music at the University of California, Riverside, co-organizer of the festival with Christopher Gibbs, began with a comprehensive portrait of Victorian and Edwardian England and the social, intellectual, and religious issues which formed Elgar and confronted him in his maturity. Maintaining a sharp contemporary eye on the contradictions and failings of this world, Adams intelligently avoided obscuring its character with anachronistic moralities. Veteran music critic Andrew Porter outlined the changes in Elgar's critical fortunes from the 1920's to the present day. He especially focused on the major London critics of his own developmental years, like Ernest Newman, Edward J. Dent, Desmond Shaw-Taylor, and others. Diana McVeagh, whose biography of Elgar was published in 1955 and her book on Elgar's music just this year, discussed various assessments of Elgar's personality and music, beginning with early memoirs by friends and associates and culminating in David Cannadine's rather harsh (and unconvincing) view of Elgar as a self-promoting opportunist. In the end all speakers agreed that Elgar was a complex man and a great composer.

The first Saturday musical program, the second in the festival, was devoted to Victorian domestic and social music. As Christina Bashford observed in her introductory lecture, the program followed roughly what would have been heard in the house of a member of the gentry in Elgar's Worcestershire. Two glees by Walmisley and Stainer represented the sort of challenging a cappella music which was written for the serious amateur choral groups so popular at the time. The performances by the Bard Festival Chorale under the impeccable James Bagwell were truly amazing for their musicality and precision. Early and high Victorian piano music was represented by pieces by Cramer, Bennett, and Mendelssohn, the presiding spirit of Victorian music as a whole. Anna Polonsky's sensitive and colorful playing could not rescue the first two from a certain tedium, while the superb Simone Dinnerstein had much better material to work with in the Mendelssohn. Thomas Meglioranza used his attractive baritone most fluently in his imaginative and vivid interpretation of Victorian parlour songs on texts by Herrick and Fitzgerald (translation of Khayyam's Rubaiyat). I can remember when songs like "Cherry Ripe" or "Where the Bee Sucks," one of a group of songs by Arthur Sullivan which concluded the program could only have been performed for laughs, but Meglioranza, not without a certain irony, plunged boldly into them and brought us a good way into the spirit in which they would have been enjoyed when they were fresh. Bagwell and his chorale continued to delight in a mixture of Catholic and Protestant church music, including two works by the young Elgar, the earlier one, "O salutaris hostia" attractive but conventional, and the later, "Ecce sacerdos magnus," impressive in its grandeur. A thoughtful and refined performance of William Sterndale Bennett's Mendelssohnian Piano Sextet by Simone Dinnerstein, the Daedalus Quartet, and Jordan Frazier, double bass, could not redeem its inherent stiffness and conventionality. Still, it was instructive to hear it once, I suppose. The last work in the program was Sir Arthur Sullivan's famous, "The Lost Chord," for baritone, piano, and harmonium, providing the heavenly lost chord itself.

There followed a very amusing program by Scottish pianist-musicologist Kenneth Hamilton centered on the piano works of Percy Grainger, which were hugely popular in their time, especially in recitals by the composer himself, and have not been forgotten in the UK and Australia today. I must confess that I used to turn my nose up at these three-minute wonders, but Mr. Hamilton's energetic playing and witty explanation of Grainger's technique have converted me. As soon as I can, I'll seek out some of Grainger's own recordings of this repertoire. A friend was recently lamenting how this sort of short popular piece has become a lost art today and are very much worth a listen. It's worth learning the once wildly popular "Country Gardens," a great thing for a party. Elgar's own bit of exotica, "In Smyrna," also appeared on the program. As an encore Mr. Hamilton regaled us with Horowitz's arrangement of "The Stars and Stripes Forever," reminding us of how very tasteful Grainger actually was.

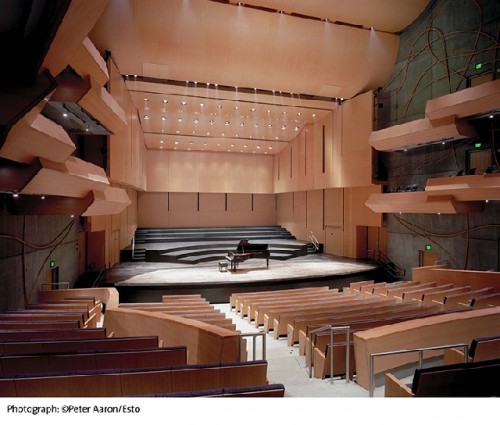

The evening concert by the American Symphony Orchestra under Leon Botstein of orchestral music by Elgar and his older contemporaries, Hubert Parry and Charles Villiers Stanford, was obviously the most substantial of the day. They first offered a supremely energetic and texturally lucid performance of one of Elgar's most Straussian works, "In the South (Alassio)" of 1903-04. The superb hall acoustics, its deep stage, and Botstein's canny way with the score produced a good deal of space around the different orchestral voices in this largely satisfying performance, compromised primarily by some rough ensemble, most notably in the crucial opening bars, and another issue, which I shall discuss at the end. Before the intermission there followed symphonic variations by Parry and Stainer, both academic compsers who were steeped in Brahms, especially in these works which looked back to Brahms' Haydn and Paganini Variations. Although they were indeed pious hommages to the master, these were both rich and enjoyable pieces, well worth hearing more often. In particular, one can see Stainer thinking that he needed to complete the picture for Brahms in a way. If Brahms stayed with the piano for his Paganini Variations and arranged his two-piano score of the Haydn Variations for orchestra, why not go further and write monumental variations for piano and orchestra? The work is indeed somewhat idolatrous, but it is vivid and full of imagination. I enjoyed the music thoroughly, especially in Piers Lane's shamelessly virtuosic and powerful performance.

These fine pieces of 1897 and 1899, as satisfying as they were, only paved the way for the work which made Elgar famous in his own time, his "Variations on an Original Theme," Op. 36, known as the "Enigma" Variations, because of a pencil note by his publisher in the score. Here the self-taught provincial leaves behind the careful Brahmsian world of the Royal Academy and plunges into a kind of music rooted in human feeling and psychology. As Diana McVeagh observed in the morning, each variation, most bearing the initials of friends, express the composer's personality through the consciousness of his friends, a quintessentiality modern artistic gesture. This major work was preceded by spirited performances of the Pomp and Circumstance Marches nos. 1 and 4 and the dark march from his incidental music for Yeats' and George Moore's play, "Grania and Diarmid." As before, the ASO played a little roughly in places, but always with energy and commitment. Botstein's interpretations emphasized excitement and clarity. As one of the visiting lecturers pointed out, the Sosnoff auditorium is close to the size and acoustic of the halls in which these pieces were originally performed, another important virtue. All that was lacking in the Enigma Variations was the subtlety of orchestral color and mood, of tempo variation, as well as the intimacy and occasional softness of tone of the finest homegrown performances—all qualties we associate with "Englishness". In comparison with Davis, Boult and Barbirolli, and especially Elgar's own recorded performances, there was indeed something missing.

Nonetheless I enjoyed these performances for their own qualities, and I'm enthusiastically looking forward to Mr. Botstein's "Crown of India," Second Symphony, and "The Dream of Gerontius" this coming weekend.

Web: http://michaelmiller.goodletters.net

e-mail: heliagoras@gmail.com