Houston Ballet

Once in a Blue Moon Visit to Jacob's Pillow

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 17, 2018

Houston Ballet

Jacob’s Pillow

Ted Shawn Theatre

August 15-18, 2018

Artistic Director, Stanton Walsh AM (Order of Australia)

Executive director, James Nelson

Music Director, Ermanno Florio

Principal ballet master, Louise Lester

Ballet masters, Barbara Bears, Amy Fote, Steve Woodgate

Stage manager, Vanessa Chumbley

Principal dancers: Ian Casady, Jessica Collado, Chun Wai Chan, Karina Gonzalez, Jared Matthews, Melody Mennite, Connor Walsh, Charles-Louis Yoshiyama

Just (World Premiere)

Choreography, Stanton Welch AM

Music David Lang by arrangement with G. Schirmer, Inc. publisher and copyright owner “Just (after Song of Songs), “Gravity for piano (four hands),” “Cheating, Lying, Stealing (for six players)”

Lighting, Lisa J. Pinkham

Costumes, Holly Hynes

Ballet master, Barbara Bears

Sons de l'Âme (Excerpts 2013)

Choreography, Stanton Welch AM

Music Frederic Chopin “Nocturne ) Op.15 No.1,” “Andante Spianto Op. 22,” “Nocturne No. 20 in C sharp minor, Opus posthumous.”

Piano, Katherine Burkwall-Ciscon

Lighting, Lisa J. Pinkham

Costumes, Holly Hynes

Ballet master, Louise Lester

In Dreams (Company premiere 2018)

Choreography Trey McIntyre

Lighting, Nicholas Philips

Costumes, The Bisou Consortium

Ballet master, Steve Woodgate

Clear (Company premiere 2007)

Music, Johann Sebastian Bach “Concerto forViolin and Oboe in C minor”

Lighting, Lisa J. Pinkham

Costumes, Michael Kors

Ballet Master, Steven Woodgate

On a hot and humid evening in the Ted Shawn Theatre, the renowned Houston Ballet, in their first visit since 1979, presented a long program of four works with two intermissions.

Contradicting the printed program the first and last works were inverted. It was arguably a well advised decision.

The evening opened with a world premiere commissioned by Jacob’s Pillow. Choreographed by artistic director, Stanton Welch AM, it is set to music by Bang on the Can co-founder David Lang.

The inventive music combined traditional and appropriated, primarily percussion instruments. There were distinct segments which equated to three different moods and dance approaches. The last part was a long chant with a female voice droning the word “just” with many modifiers.

The net impact was disjunctive; engaging the audience, and then breaking away in another direction. There were highpoints but the work failed to resonate and adhere. It was prolonged, inscrutable, and needed more connectivity.

The piece started brightly with a couple, Jessica Collado and Christopher Coomer, interacting in a probing, tentative mode, on the cusp of an argument grasping for commonality. Any one of us can identify with that phase of a relationship. They alternately came together and pushed off.

The stage was then dominated by a single male dancer, Brian Waldrep, attired in an edgy, black suit. There were stunning, inventive moves and gangster-like, aggressive thrusts, swoops and turns suggesting transgression. A second, similarly attired male entered walking a square around the soloist. He returned for a duet and then other men developed into an ensemble.

Enter a striking, tall blonde woman, Mackenzie Richter, in "corporate" attire of pinstriped pants over fishnet stockings and black pointe shoes. Given the post modernist mode of the experimental music the infusion of classical technique and style is arguable the signature of Welch and his company.

Although this was our introduction to the company the assumption is for the commission to expand its reach. That was confirm by the other two of Welch’s pieces.

For the concluding segment of “Just,” with music as a drone/ mantra, a woman appeared in a beige silk slip. Echoing the segment with a solo male dancer she was gradually paired then grouped. Between the repetition of the word ‘just’ one struggled to grasp the drift and significance of the modifiers and how each phrase generated specific related movements. As the work appeared to lag on it was plausible to feel less and less engaged with its intentionality.

Because the piece proved to be so demanding it opened the program when the audience was fresh and most receptive. The response to the new work was primarily reserved and confused.

Ending the evening with Clear, again by Welch, to music of Bach, with exquisite classical ballet for seven men and one woman, proved to be easier on the ear and eye. It is the kind of work that delivers affirmative impressions for an audience. The programming reversal allowed the audience to leave on an upbeat.

The work celebrated the company's depth in male dancers. The vocabulary of movement presented spactacular pirouettes, jumps and sweeping turns. Virtuoso individual sequences of repeated turns were accompanied by bursts of applause.

The piece comprised a solo, duet, as well as a trio. With the focus on male dancers the function of a single female, Jessica Collado, was obscure. Treated as an abstraction she provided a comparative accent. Taken as a narrative, her inclusion in dominating male company, was inconclusive. Significantly, her loose costume of pants and top emphasized similarity to the men rather than gender difference.

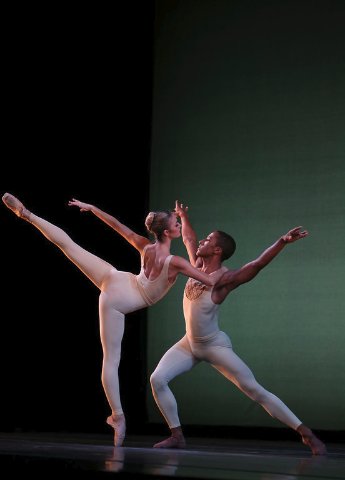

Opening the second part of the program Welch’s Sons de l'Âme was the most sublimely traditional of his selection of three dances. The three short piano pieces by Chopin, performed off stage by Katherine Burkwall-Ciscon, each featured a different pair of dancers. They were attired in matching white unitards.

The company comprises 60 plus dancers of which 31 appeared at Jacob’s Pillow. It was announced that four are former Pillow students.

This work revealed the strength and core of an exquisitely trained company. There was an extensive vocabulary, of turns, lifts and movement en pointe. It was intriguing to compare and contrast the couples. The array of pas de deux vignettes seemed both inspired and culled from romantic ballet as refreshed by a contemporary approach. It aptly conveyed how Houston Ballet preserves tradition and embraces the new.

Several years ago at Pillow we saw the final performances of Trey McIntyre's company. He opted since then to pursue a career as an independent choreographer. Some years ago, he was a dancer and fledgling choreographer for Houston Ballet.

His In Dreams, set to music of Roy Orbison, was such fun. It was difficult to decide which one liked more, the plaintive, melancholy country rock twang music of Orbison, or the zesty, exciting dance.

In 1950s rockabilly attire, think Patsy Cline, there was the inventive idea of three women and two men. That led to variations of snap the whip and odd girl out. At times the three ladies were bookended by the males. With some tension there were configurations of two couples and a woman at the end tagging along.

A suite of three minute songs, singles or 45’s back in the day, engendered inventive responses to Orbison's signature pathos. Behind coke bottle glassses, and rigid onstage posture, he was not a pretty boy rocker. Orbinson was a stand and deliver, no nonsense performer. He was known for compelling and credible melancholy songs of lonely guy rejection. In 1987 they earned him induction to Cleveland's Rock 'n' Roll Hall of Fame.

As they say in Texas, y’all come back yah heah.