Boston Modern by Judith Bookbinder

Definitive Study of Boston Expressionism

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 18, 2014

Boston Modern: Figurative Expressionism as Alternative Modernism

By Judith Bookbinder

University of New Hampshire Press

372 Pages, illustrated with notes and bibliography, 2005

ISBN 1-58465-488-0

In a meticulously researched and documented book Boston Modern: Figurative Expressionism as Alternative Modernism the Boston College adjunct professor, Judith Bookbinder, has provided an invaluable and penetrating overview of a dominating figurative tradition from the 1930s through the present.

There is a poignant downside to this scholarly effort in a field that has attracted scant attention. Reading through the chapters we connect the dots of how and why Boston came to be regarded as a provincial backwater of what Irving Sandler has described as the New York based, post war Triumph of American Art.

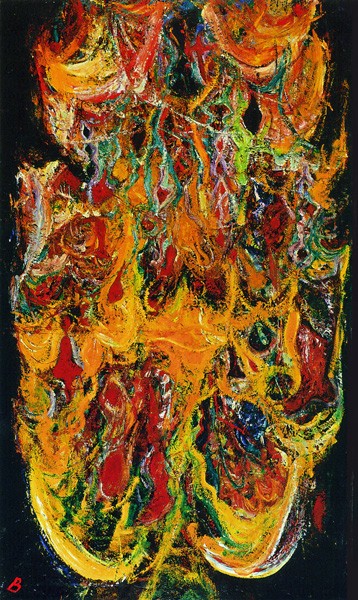

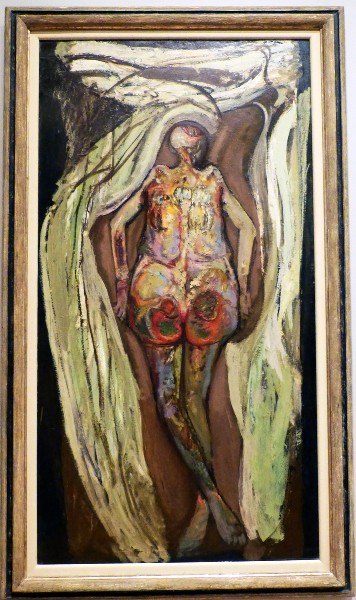

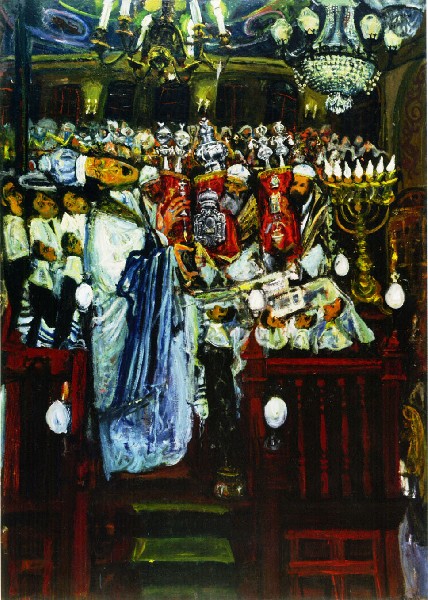

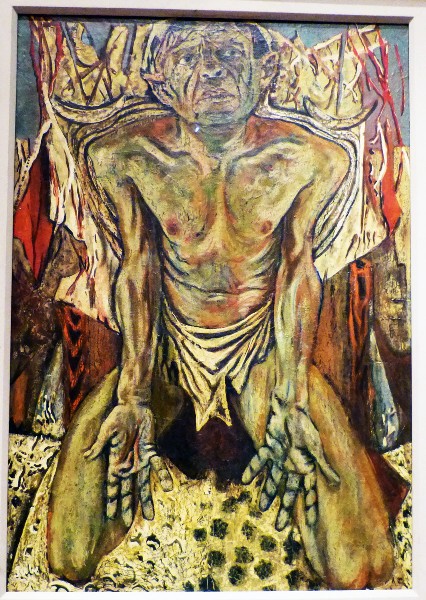

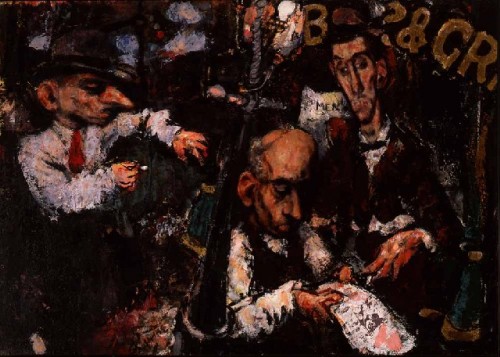

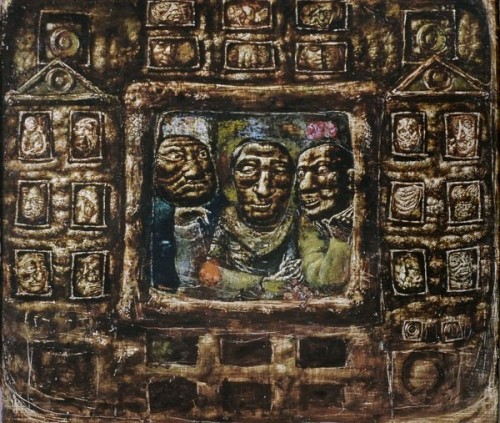

Other than glimmers of success, particularly by the earliest exponents of Boston Expressionism- Karl Zerbe, Hyman Bloom and Jack Levine- for the most part their progeny-David Aronson, Arthur Polonsky, Lois Tarlow, Barbara Swan, Bernard Chaet, Kahlil Gibran, John Wilson, Reed Kay- struggled for recognition.

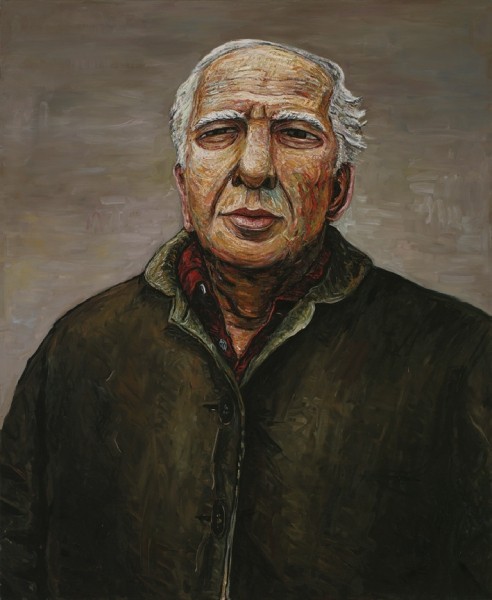

Although not native to Boston Bookbinder adds Philip Guston to the mix because of close ties particularly as a University Professor at Boston University. The students who most reflected Guston’s controversial return to the figure following decades of formalism were Jon Imber and William Harsh.

Excluded by Bookbinder but essential to this thesis are Henry Schwartz, Domingo Barreres, Miroslav Antic and Gerry Bergstein. They were important teachers of figuration in the tradition established by the German born Zerbe at the Museum School.

Another important artist is Stanley Pransky who died young a suicide. The Warde-Nasse Gallery showed his work in the late 1960s which I reviewed for Boston After Dark. Arnold Trachtman a trenchant rad from Lynn with expressionist roots has rarely gotten adequate recognition from the art world.

In an historic incident in 1948 James Plaut, then director of the Boston Museum of Modern Art, issued a statement "Modern Art and the American Public" when the organization was reconfigured as a kunsthalle. The Institute of Contemporary Art struggled through decades of near extinction prior to its relocation several years ago to Boston’s waterfront.

Celebrating the anniversary of the ICA which was founded in 1936, under then director, David Ross the Institute in 1986 reexamined that controversy with the exhibition Dissent: The Issue of Modern Art in Boston. By then the ICA, other that the short lived annual, Boston Now, had come largely to ignore Boston artists. In 1979 Ross’s predecessor, Stephen Prokopoff, mounted Boston Expressionism: Hyman Bloom, Jack Levine and Karl Zerbe.

In its earlier incarnation the Boston Institute of Modern Art regularly championed Germanic art and Bostonians who fell under its influence. Today figuration in Boston is the focus of the Danforth Museum of Art founded in a former Framingham school building in 1975.

The break from MoMA, of which it was initially a satellite, also represented a divergence from French modernism embraced by New York to the Northern European, Dionysian/ Romantic tendencies of Germanic angst from Mathias Grunewald to Max Beckmann, George Grosz, Oskar Kokoschka, Egon Schiele or more expressionist flavored School of Paris artists from Chaim Soutine to Georges Rouault.

As Bookbinder documents Kokoschka taught in the Berkshires summer program of the Museum School. Susan Hodes was among the artists who studied with him.

Although this book was published almost a decade ago it is relevant to the ongoing research into origins and definitions of Figurative Expressionism which I have been sharing with scholar and curator Adam Zucker.

We have come to identify bi coastal manifestations of Figurative Expressionism, primarily in the 1950s and 1960s, as responses to the dialogue of a Return to the Figure during the ascendancy of Abstract Expressionism. Our focus has been on developments in Provincetown, New York, Chicago, San Francisco and Boston.

While the subtitle of Bookbinder's publication is Figurative Expressionism as Alternative Modernism she is using the term more broadly and out of sync with how it applies to other groups of artists under that umbrella term.

Significantly, the origin of Boston Expressionism, in the development of teenagers Bloom and Levine as tutored by Harold Zimmerman, in a South End settlement house, and by Harvard’s Denman Ross, predates the development of Abstract Expressionism. Initially, with bright impasto paint and edging toward abstraction, Bloom was recognized by the New York artists and the critic Clement Greenberg as a running mate of formalist abstraction.

In 1950 he was one of seven artists (including Arshile Gorky, John Marin, Jackson Pollock, and Willem de Kooning) to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale. In a 1954 conversation with Bernard Chaet, Pollock and de Kooning called Bloom "the first Abstract Expressionist artist in America." The same year, Bloom had a major retrospective of his work at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

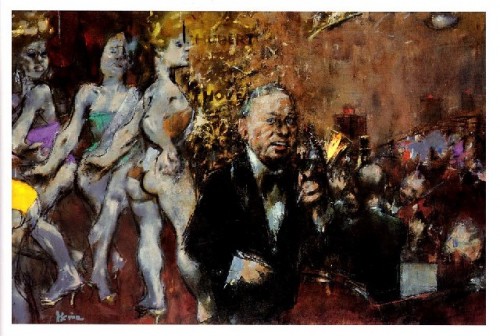

After mustering out of the military Levine married the artist Ruth Gikow and moved to New York but continued to be a Red Sox fan. He was regularly included in the Whitney Annuals and was widely recognized for the mordant social and political commentary of his work.

Uniquely, virtually all of the Boston Expressionists were Jewish. Mostly sons of poor immigrant, orthodox parents they struggled with the Biblical taboo against the Graven Image. That resistance gave a resonance of Judaica to their work which often explored Biblical subjects. In the struggles to break away from their religious traditions and heritage the narrative, emotional work became a chronicle of personal exploration. The paintings were arenas for self discovery. In the context of the avant-garde and modernism this approach had become anathema.

As Bookbinder documents most of the artists were from poor, Eastern European Jewish communities unlike the more sophisticated and assimilated German Jews including wealthy New York merchants chronicled in the Stephen Birminghman book Our Crowd. The artists mostly grew up in the poor Boston communities of the South End, Roxbury and along Blue Hill Avenue. They were not children of the wealthy Jewish communities of Brookline and Newton which are more reformed than orthodox or Hassidic.

Another polarity, for Levine in particular, was the scathing satire of Bertolt Brecht and the political graphics of George Grosz as well as the paintings of Beckmann and Kokoschka. The German born Zerbe, particularly as dean of the Museum School, was a primary source and direct connection to European expressionism.

Bookbinder relates how Levine met Grosz, then an exile, at a New York party. Imagine being a fly on the wall for their conversation.

In addition to aesthetic alternatives between Germanic and French there were political ones. By the 1940s we were at war with Germany. That meant the closing of Harvard’s seminal collection of Germanic art, the Busch Reisinger Museum. It cast a pall over Boston’s cultural embrace of the Germanic tradition from the ICA to the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Similarly during WWI, when Marsden Hartley returned to America, his gallerist, Alfred Stieglitz, refused to show the brilliant and now much admired German Military Series. Stieglitz dispatched Hartley to paint American landscapes in Maine, Gloucester and the South West. The work never again reached the brilliance and originality of the early paintings.

Considering this wartime climate the School of Paris embraced by MoMA flourished. Its artists dominated the debates focused on modernism while expressionist figuration came to be regarded as reactionary and counter revolutionary. One finds elements of this in Serge Guilbaut’s seminal and controversial book How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art.

This notion of figuration as counter to the avant-garde breakthroughs of post war American art is an aspect of why Figurative Expressionism never took hold in mainstream critical thinking. This movement continues to be misunderstood and marginalized.

Which is precisely why Bookbinder’s research is so important and essential. Particularly when considering that the Museum of Fine Arts has arrogantly failed to research and exhibit this now nearly 75-year-old tradition of art in Boston.

In 1986 Trevor Fairbrother curated The Bostonians: Painters of an Elegant Age, 1870-1930. That is the precise tipping point when the mainstream of Boston art passed from charming Brahmin painters of ersatz impressionism to the great unwashed of Jewish expressionism. His tepid exhibition brought to a close the attempts of the MFA to survey Boston art from Colonial times through the last gasp of the cultural hegemony of the founding fathers and their progeny.

Ironically, also in 1986, the DeCordova Museum mounted a pratfall ineptly curated by Pamela Allara, The Humanist Vision: Expressionist Art in Boston, 1945-1985. I wrote a scorching review in the daily Patriot Ledger. Nearly 30 years have now passed since that botched attempt to survey figuration in Boston.

When the architect Frank Lloyd Wright lectured he stated that what Boston needed was “A hundred first class funerals.”

Through the William and Saundra B. Lane Collection the MFA serendipitously was able to fill gaps in American modernism, a field it had scorned, including choice works by Zerbe and Bloom. The gift included 6,000 photographs, 100 works on paper, and 25 paintings. It includes Charles Sheeler’s entire photographic estate of nearly 2,500 works; an equal number of images by Edward Weston; and 500 photographs by Ansel Adams. The Lane Collection also features paintings and works on paper by major American modernists, including Arthur G. Dove, Georgia O’Keeffe, Stuart Davis, and John Marin, as well as Sheeler.

Scandalously, the MFA still does not have a major Levine like MoMA’s "Feast of Pure Reason" "The String Quartet" at the Met, or "Gangster’s Funeral" owned by the Brooklyn Museum.

Ironically, those seminal works came, free of charge, to the museums transferred during the closing down of the WPA artists program funded during the Great Depression. Similarly, the Art Institute of Chicago acquired its iconic "American Gothic" from the WPA for which Grant Wood was not paid a dime.

While Bookbinder’s book is scholarly it is not critical. It focuses on biographies and works of the artists but offers few assessments of their relative accomplishments. The assumption is that every artist she discusses is equally worthy of attention. Actually more than a few are mediocre. It is the standard art historical approach of providing thorough information while not addressing where artists stand in the spectrum of mainstream critical evaluation and market worth.

During a recent visit to the Cape Ann Museum, for example, we were surprised to learn that the museum had the choice of fifty works from the Bernard Chaet estate. In addition to writing a standard text on drawing Chaet, a graduate of the Museum School and exponent of its traditions, for many years was a professor at Yale University. Through Alpha Gallery exhibitions I had long admired the work. We spoke at length about Yale when I wrote a piece on the school for Art News. I was close to Lester Johnson who Chaet hired to teach at Yale.

When I mentioned this to an artist friend he stated that the work is inexpensive. From an auction link I learned that paintings sell from a few hundred dollars to under $10,000. When the art market sets such low evaluations there is little incentive for research and exhibitions. As with everything else ambitious curators and art historians follow the money. If there is none the trail grows cold.

Compared to other post war movements works by figurative expressionists and their off shoots are grossly undervalued.

A case in point is how Guston came to be vilified when he abandoned formalist abstraction and returned to social and political commentary. He was recruited by Aronson to teach at BU. Bookbinder discusses how he was not a great teacher but through his work and example was a formidable inspiration to the graduate students under his care. Imber described being treated as a peer entailing long hours of dialogue.

Because of his regular commutes to Boston (like those of Alfred Leslie who replaced him) he called the MFA’s contemporary department and offered them the pick of his studio. He was insulted when informed that they would be interested only in one of his older abstractions. The MFA much later acquired a Guston that does not compare well with what it might have had.

While the Museum School and Mass College of Art have diverged from teaching figuration it remains the paradigm at BU. The initial intent from Zerbe to Aronson was to provide students with techniques and understanding of materials to give them the tools to find their own means of expression. Instead this has resulted at BU in one of the nation’s most conservative programs despite a tradition of progressive professors from Guston and Leslie to the British artist, John Walker.

When I taught an avant-garde seminar at BU I was always surprised by the resistance and conservatism of the students. There were howls of protest and debate when I started each semester with a video of John Cage including his famous 4’33” which is performed by a pianist and scored for silence. At BU Marcel Duchamp was a tough sell. By the end of the course attempts to shock them were met with shrugs of what else is new?

As a teenager in Boston I grew up with its exotic flavors of Jewish Expressionism. I was intrigued by seeing Bloom’s drawings at Hyman Swetzoff’s gallery and later at Boris Mirski. During a semester at Harvard Summer School a fellow student, Judy Goldberg, took me to see her father’s remarkable collection of Blooms including a disturbing female cadaver drawing.

As an undergraduate at Brandeis I studied drawing and design with Polonsky and painting with the social realist Mitchell Siporin. I recall when Mitch invited Levine to give us a slide presentation. Inspired by this I made some now lost "Levines."

A balance to their approach was derived from the New York, avant-garde sculptor and print maker Peter Grippe. He maneuvered to discredit Polonksy who was then hired by Aronson at BU. Polonsky’s former wife, the artist Lois Tarlow, was a colleague of many years at Art New England.

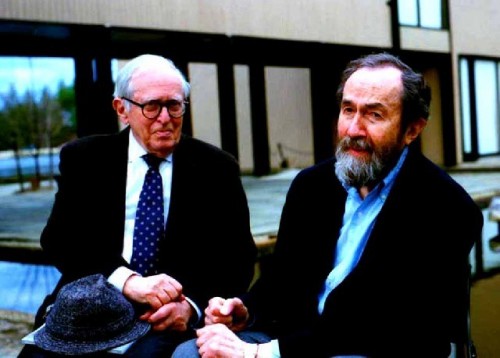

As a friend of David and Nancy Sutherland (since divorced) I got to know Levine when they were working on the 1989 documentary Jack Levine: Feast of Pure Reason. David loved Jack’s then current work including the insightful and hilarious "Sinatra at Vegas." The art world had by then abandoned him but Jack was still going strong. He hated critics but we got along just fine. It was such a privilege to know him.

During one of our outings we visited the department of drawings at the Fogg Art Museum. We viewed works that Jack and Hyman created as teenagers under Zimmerman and Ross. I devoured Bookbinder’s insightful and detailed account of this period of their unique development. I knew and admired but never penetrated Bloom. He was reclusive, mystical and had many interests in Eastern music and philosophy. Briefly he taught at Wellesley but mostly supported himself modestly through sales of paintings.

At one point I surprised him by whispering into his ear “Max Rinkel” (1894-1966). It was the name of the therapist who treated him with LSD. It inspired some of his most remarkable drawings of tangled forest and piles of fish skeletons. Hyman was out there.

I was pleased slowly to devour and absorb this book. It is essential to the ongoing dialogue about Figurative Expressionism. But it also evoked a dispiriting reflection on why art created in Boston continues to be marginalized.

It angers me to comment that the Fogg has never shown its treasure trove of Bloom and Levine juvenilia. It remains visible by appointment. When is the MFA going to get off its anti Semitic ass and honor the Boston Expressionists? Bookbinder’s superb publication provides a compelling template for a stunning exhibition.

Boston critic Greg Cook on Abject Expressionism.