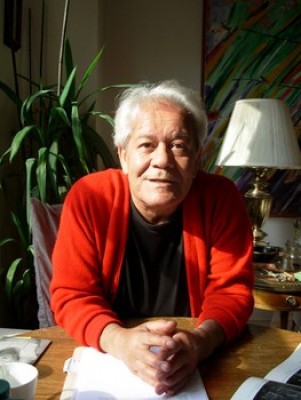

Artist and Activist Lloyd Oxendine (1942-2015)

Worked to Promote Native American Art

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 18, 2015

In 2006 while curating two exhibitions of Native American art for the gallery of New England School of Art & Design/ Suffolk University I met with and interviewed a number of artists. Often they passed me along to others.

A name that cropped up as essential to talk with was Lloyd Oxendine.

Primarily in the 1970s he had done important work. This included founding a gallery in New York, American Art, in 1970. He maintained it until 1978. It was the precursor to the American Indian Community House Gallery, for which he curated off and on.

In 1972 Oxendine, a member of the Lumbee Nation who died on August 5, published the first major feature article in a mainstream art publication. “Twenty Three Contemporary Indian Artists” was published in Art in America’s July-August issue. In the decades since then his singular effort has rarely been duplicated.

He gave such notable artists as R.C. Gorman, George Morrison and Frank La Pena, their first New York shows. As Director/Curator of the AICH Gallery he organized 40 exhibitions.

As a curator Oxendine was well trained with a degree in art history from Columbia University. He studied at the Arts Students League while at Columbia where he also earned an MFA. He was given an honorary doctorate by the London School of Design.

Afternoon light flooded through a spacious apartment near the Columbia campus when we spoke in 2006. What follows is excerpted from interview.

On the table was a copy of “Twenty Three American Indian Artists.” Working with the editor, Brian O’Doherty, the entire issue was devoted to the subject of Native art. Oxendine produced some other documents of the period but little of the work was familiar. I recognized an early abstract work by Peter Jemison, who early on worked with Oxendine. The reproduction dated from when he was a young artist, newly arrived in New York, showing with the prestigious Tibor de Nagy Gallery.

Looking back at the activism and protest/ political arts of the 1970s it is complex and puzzling to ask why so little endured and carried forward to the next generation. Much of the work produced then today seems strident, polemical and cartoonish. Many of the issues, agendas and creative work were inspired by the Vietnam War, Civil Rights, Drugs and Gay Pride.

As a Native artist we inquired about identity and how that impacted his work and activism? “In my case I was born into (1942) and brought up as a part of The Lumbee Nation of North Carolina,” he said. “As opposed to being an orphan. Or someone who was brought up as white or black who may have the blood but not the characteristics. America has done a good job of destroying Indian culture. What's left are descendants of Indians saying ‘my ancestors were Indians.’ These are often people having little Indian blood. Indians can also be racist. There are Indians who relate to their white or black side. Who can say that those White Indians are not Indians?”

The Lumbee people were recognized by the State but not the Federal government. Overall he states that it is the 6th largest tribe but was not decimated. “We were the Civilized Indians,” he said. “With the first Indian college in the late 1800s, Pembroke Normal School, and the University of North Carolina at Pembroke which had more Indian than white students.”

For his generation it is unique that Oxendine received an Ivy League education. From UNC he matriculated to Columbia with a major in art history and an MFA in Painting. He also studied at the Art Students League.

“You dream big and get what you want,” he said. “Before (Columbia) I wasn’t interested in Indian stuff. There was nothing to be interested in. The only thing happening was Santa Fe and Western art and there was no Indian Gallery outside of the Southwest. We were teachers and educators and we went to where the jobs were. I didn’t have to say ‘I’m Indian.’ I was Indian. I went to Indian schools. In North Carolina when I was growing up there were three bathroom facilities: Black, Indian and White. The Indians were a slight niche above Blacks who worked in the fields. We (The Lumbee) were farmers. The surviving land that we owned (after swindles and scams) was swampy like that of the Seminoles. We raised cotton and tobacco. The whites hated us and we knew that they needed someone to be better than. There was a Ku Klux Klan rally in 1956 and the Indians surrounded them with guns. That was the end of that.”

Asked about his own family he said that Oxendine is an Indian name from the original Algonquin language, which he does not speak. The artist is fluent in five languages used when he lived in Europe for four years. His (second) wife is Swiss.

Just how did his interest in Native Art develop? Apparently that started as a student at Columbia when he was astonished at how little published material existed on the topic of contemporary Native American Art. For a course he wrote a research paper on the white explorer/ artists George Catlin and Karl Bodmer. He began to ask around and collect slides. There was a 1942 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art organized by Rene d’Harnoncourt but nothing since then. There were also books on Indian art by Jamake Highwater which sold well. Indians later exposed the fact that he was born George John Markopulos in 1928.

“Most of the information on Native art comes from anthropologists,” Oxendine said. “About which there is a love/ hate relationship. Indians resent that but it’s true.”

He is also critical of revisionism and commented how in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1970s there was a “resurgence of Iroquois to be more traditional.” He was most active and productive at that time. For several years in the 1970s he operated the American Art Gallery in Soho. He felt it was very important to try to sell the work to support the artists. He also tried to get the work reviewed.

When the gallery closed he spent the next decade in Europe and San Francisco. Upon returning to New York in 1985 he became Director/Curator of the American Indian Community House (AICH) Gallery/Museum. There were frustrations as AICH had a mixed agenda including health and social services. This tended to limit and define grant writing and funding. He advocated for a mandate to identify and develop a core of New York based artists. He expresses hard feelings about leaving the organization. Peter Jemison took over for a time. Jaune Quick to See Smith has discussed how she, Jemison, and other curators developed a circuit for traveling small shows but eventually that broke down.

Oxendine continues to be active. He is a member of the Multi-Cultural Advisory Committee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He has served as a consultant and panelist for the Rockefeller Foundation, National Endowment for the Arts, the New Museum of Contemporary Art, The New York Foundation for the Arts, the College Art Association and numerous Native based arts organizations. He has lectured and published extensively.

He was frank about battle scars earned in years of the cultural wars. “I started out as a white man,” he said. “I came to a traditional and spiritual position. In the 1970s I grew my hair long and started hating the white man. It didn’t start all at once. I got carried away but came to learn that you can’t hate people. I needed a break. We were destroying ourselves and becoming like crabs in a pot. I tried to help Indians to do things Like consulting with Amerinda to develop a site that showcases Indian artists living and working in New York. It provides information on grants and services. AICH provides social services and referrals on conditions such as diabetes and AIDS. It provides free lunch. When I ran the gallery program I did a lot of PR, writing and sending more than 500 press releases. Once in a while you got a live one and occasionally a Times review.”

Compared with his program and mandate for exhibitions under his watch at AICH he is critical of the current efforts of the National Museum of the Native American (NMAI). “They have gotten either bad or no reviews,” he said. “It is a government organization (Smithsonian) and does not represent Indians. It represents a Government approach to the arts and employs Indians but it does not speak for Indians. We at Amerinda are trying to represent the community. We want to know what they need. And not just to show what is the latest and best.”

He expresses opinions about organizations that present minority and fringe groups. “I am academically against what I call ‘Ouch Galleries.’ Meaning ‘I’m hurting and I’ll start a gallery and tell you all my problems,’ “ he said. “My wife (first) said ‘Why don’t you leave all this Indian stuff alone? We split up.”

There has been a lot of criticism of the NMAI in Washington, D.C. particularly the lack of clarity of the installation of the permanent collection. I asked why he thought it was a mess? “Did I say that,” he asked? “It’s America’s Indian Museum. But there was no concrete thematic planning of the exhibitions. It is too cluttered.”

He discussed some of the complexities of the legacy of George Gustav Heye who in the early 20th century amassed an enormous collection of traditional Native materials. This eventually belonged to the State of New York.

It was originally housed in a museum on 155th Street and Broadway. There were many intrigues and scandals, the subject for another time. A decision was made to move the bulk of it to Washington, D. C. with a stipulation to leave a part of the collection in New York. Hence the current NMAI in a Federal building located at Bowling Green in Lower Manhattan.

While NMAI shows contemporary work, Oxendine expresses concern that the agenda should be to have the work seen in the mainstream venues from MoMA and the Whitney to PS1. He is critical that being content with showing contemporary work at NMAI is not proper networking. To make his point he comments that Indians have been standoffish and not worked with white people. “Indians have not worked with white people and gotten to know them. In that sense Blacks have had greater success.”

We asked if he had concerns about publishing critical comments. He responded that “What makes Indian art? Because it’s against white people? How to make it into a successful gallery? Like what is shown in Santa Fe. People want romance. They want art that is reaching out and communicating (kitsch). They buy that art.”

The drift of our dialogue made me feel uncomfortable. With years of good work and activism he has earned respect. “I’m not going to be quiet,” he said. “I can do things and choose my fights.”

That ends excerpts from what Oxendine told me almost a decade ago. So much has changed since then. It is interesting to go back and feel the strength and passion of what he had to say. He was indeed a strong and committed force during a time of daunting indifference from the mainstream art world.

He carved out paths for others to follow. Who today can walk in his moccasins?