Gonzo Aesthetics of Giuliano’s Poetry

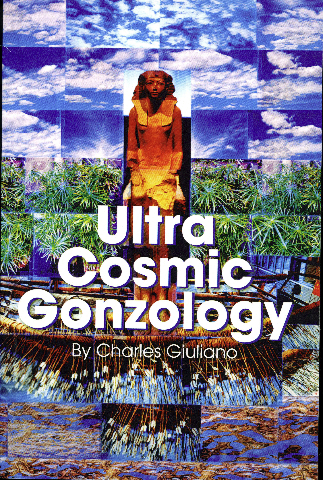

Ultra Cosmic Gonzology

By: Robert Henriquez - Aug 18, 2016

With his two previously published books of poetry, Shards of a Life and Total Gonzo Poems (2015)—and now with his third and latest selected poems, Ultra Cosmic Gonzology (2016)—Charles Giuliano has led us through an outburst of poetry recounting the wisdoms and excesses of his rich and eventful life.

During this rapid accretion of poetic energy, Giuliano, a hipster septuagenarian well into the age of decreased creativity and mobility for most, has compiled, in the span of three years, a vast anthology of more than four hundred poems. These are like discrete flashes of a newly manifested type of creative energy casting a wide shine on the possibility of an avant-garde approach or style in Giuliano’s poetics. Let me posit here that the ideal conditions for framing Giuliano’s work in a contemporary avant-garde praxis rest in part on the peculiarities of the word “gonzo.”

As a point of thorny contention, the matter of rightful ownership and meaning of the term “gonzo” still persists. For decades the word gonzo and the thoughts attributed to it seemed mired in semantic confusion. By all accounts the etymology of the word itself is not without its problems.

Although now encompassing multiple meanings, the word gonzo was first uttered as an expression of defiance and victory by Giuliano—a phonetic utterance, so to speak. It appears to be at times a “signifier” in search of a determinant “signified.” The etymological account of its development through the years delineates a pattern of radicalism that keeps it outside the norms of bourgeois society.

Giuliano, a scion of bourgeois affluence turned progressive radical, would boastfully lay claim to the word’s provenance and fate, knowing all the while that gonzo is not to be a bourgeois word. He made his case in the poem Birth of Gonzo—(Total Gonzo Poems pp. 244–245), and other published articles dating back to the 1970s. He supports his claim with due diligence by publishing three volumes of poetry, which should put any linguistic issues to rest.

Now that Giuliano has introduced the word “gonzology” into the fray, is it possible for the word gonzo to earn its own “ism” suffix and be absorbed in the Western praxis of literary art? Or is gonzo the banner word to be carried at the top of Giuliano’s poetic exercise and used to mark an eventual bid for an avant-garde praxis? My answer to the latter is yes, and gonzo is the de facto operative word.

Assuming, for the sake of argument, that the gonzo poems as a whole form a theoretical reasoning to advance a putatively new poetic avant-garde. Then what’s needed, in this case, is an argument of convincing possibility that connects Giuliano’s poetics to avant-garde practices. To begin with, the term avant-garde, which identifies trends and movements ahead of their time, is also complicated and overused. Moreover, the term avant-garde always refers to group formations—groups of artists banding together to overturn the status quo of the Establishment.

The conception of an historical avant-garde is an effort to invariably assert the historical authenticity of art as a radical power for change. That said, most of the avant-garde movements that have successfully challenged the academies throughout the twentieth century—from Dadaist, Futurist, Surrealist to Beat, Lettrist and more—have been somewhat sublated into established norms, such as “Experimental Literature,” in the case of poetry.

Central to regarding gonzo poetics as a neo-avant-garde practice is in the categorical authority of the new. In a non-traditionalist contemporary society, aesthetic tradition is deductively questionable. The new gains its authority not by negating prior artistic exercises, as styles often do; it essentially negates tradition as an inescapable fact of history. To that end, the authority of the new ratifies the contemporary principle in art.

Gonzo poetics by all accounts is new and invariably radical, oppositional, and non-traditional. Giuliano recognizes newness as an aesthetic category of contemporary art. One that is grounded in hostility to mainstream values and traditions characteristic of “bourgeois-capitalist society.”

As a new poet, Giuliano laments the reflexive negativity coming from a putatively uptight orthodoxy. By his own words he fiercely defends his position to inveigh against tradition: “Dissent is the essence of social, political, and artistic progress … Ultimately it is not the academy that prevails but the efforts of artists to subvert and destroy it … There is joy in anarchy … We must destroy in order to create anew.”

Gonzo is not a movement (not yet anyway), nor is it connected to any other avant-garde groups. It is a brand-new poetic practice with its objective and methods pointing toward a bebop tempo of “asyntactic poetry.” Clusters of words are strung jointly in a proprietary way to become language. Language, in turn, dictates meaning, thus keeping it all in context.

Key aspects of Giuliano’s poetry include the idea that asemantic-poetic sentences can actually possess meaning, and that it can also be used as poetic means to revolutionize poetry itself as a model of the gonzo revolution. Verses are made of few words, at times, just one will do the trick. Digressions are frequent, but Giuliano always returns to previous moments after amplifying them with clever anecdotes and convincing narratives. There is also an underlying erudition to Giuliano’s means of expression—transitions and transmutations give way to uncovering the unfamiliar. The reader must get some grasp of the subject matter at play in the poems to get the message. All of that is part of the method and style of the avant-garde.

His affinity for generating incomparable “beats” in free-verse lines helps in cultivating a percussive style that works its way through more than four hundred poems. There are no rules or traditions as of yet, but there is a method in the fine gonzo madness—the conception of unusual, if not extreme scenarios—that propels the poems bopward.

In his third tome of poetry, Ultra Cosmic Gonzology, Giuliano once again opens his world to the reader in intimate and intriguing ways. He reveals himself as an equal opportunity thinker, a master chronicler of his own life and times and, surprisingly, as an accidental poet who got it right once again, the third time around. More importantly, he may now be considered the quintessential avant-gardist creator of gonzo poetry.

Finally, let’s take heed to this paraphrase: “We must dare, and dare again, and go on daring!” (Georges Jacques Danton, Paris, Sept. 2, 1792). Readers beware, you miss the beat, you forgo the bop—traditionalists be damned!

Essay copyright, 2016, by Robert Henriquez. All global rights are reserved.

Ultra Cosmic Gomzology is availible at Amazon for $20. The book is richly illustrated with 402 pages. It will be launched with a reading at Gloucester Writers Center, 126 East Main Street, on Wednesday, August 31 at 7:30 PM.