Aspen Santa Fe Ballet at Jacob’s Pillow

Diverse Program by Renowned Regional Company

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 20, 2011

Aspen Santa Fe Ballet

Founder, Bebe Sheweppe

Artistic Director, Tom Mossbrucker

Executive Director, Jean-Philippe Malaty

Production Stage Manager, Eric Johnson

Lighting Supervisor, Seah Johnson

Dancers: Katherine Bolanos, William Cannon, Sam Chittenden, Katie Dehler, Seth DelGrasso, Samantha Klanac, Nolan DeMarco McGahan, Emily Proctor, Seia Rassenti, Joseph Watson

Program

Uneven (2010)

Choreography, Cayetano Soto; Music, David Lang; Stage Design, Cayetano Soto, Cellist, Kimberly Patterson; Costume Design, Nete Joseph; Lighting Design, Seah Johnson.

Dancers: Katherine Bolanos, William Cannon, Sam Chittenden, Katie Dehler, Seth DelGrasso, Samantha Klanac, Nolan DeMarco McGhan and Joseph Watson.

Stamping Ground (1983)

Choreography, Jiri Kylian; Music, Carlos Chavez (Tocata para Instrumentos de Percusion), Set Design, Jiri Kylian; Costume Design, Heidi de Raad; Lighting Design, Heidi de Raad; Lighting Design, Joop Caboort; Stager, Patrick Delcroix.

Dancers: Seia Rassenti, Nolan DeMarco McGahan, Samantha Klanac, Emily Proctor, William Cannon, and Joseph Watson.

Red Sweet (2008)

Choreography, Jorma Elo; Music, Vivaldi and Biber; Costume Design, Nete Joseph; Lighting Design, Jordan Tuinman.

Dancers: Katherine Bolanos, William Cannon, Sam Chittenden, Katie Dehler, Seth DelGrasso, Emily Proctor, Seia Rassenti, Joseph Watson.

The return of the popular Aspen Santa Fe Ballet filled the Ted Shawn Theatre of Jacob’s Pillow with an attentive, spell bound, and enthusiastic audience last night. They presented three fairly long works- Uneven, Stamping Ground, Red Sweet- that could not have been more diverse. There were two intermissions.

The company was founded in Aspen, Colorado in 1996 by Bebe Schweppe, and added a second home, in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 2000.

In so doing Schweppe brought sophisticated and compelling dance way out West. Based on what we experienced perhaps one might say far out West.

While we were presented with only three examples of their work this appears to be a regional dance company with ambition that extends beyond an annual run of The Nutcracker.

This is a challenging company of superbly trained and conditioned dancers, noted for their stamina and athleticism, with many commissions of dances created by leading, global choreographers. It differs from the norm of companies built around a single choreographer. It results in the diversity we experienced but it also makes somewhat elusive the ability to identify its specific style and signature.

For the regular audience of the company that may prove to be a positive factor. Season after season they present innovations and surprises. This is not a company that wears out its welcome.

They also serve as a school with a program of Mexican dance that includes 500 children in New Mexico and Colorado. It is also notable that the axis between Aspen and Santa Fe is far more upscale than the norm of rural America. The region attracts seasonal second homers and tourism for its mix of balmy winter weather in Santa Fe and winter sports in Aspen. That forms a well traveled base for the kind of sophisticated arts that flourish in this matrix of the South West.

They perform before an audience that is likely to be well versed and sophisticated. This enhances the ability to attract the best dancers and choreographers. The company also brings in traveling dance companies. They are often on the road as a top attraction for Jacob’s Pillow and other venues.

In the lighting design by Seah Johnson for Uneven from high on the edge of stage left there was a strong fixed spot creating an angled beam that illuminated that side while the other remained dark. That evoked a visual metaphor for Uneven. Rendering the stage in chiaroscuro.

Another locus was provided by the musical composition of David Lang. There was a minimalist, repetitive sound track, an ostinato suggesting the compositions of Philip Glass. The cellist, Kimberly Patterson, provided a staccato, percussive interaction. The combination provided a tense, nervous and anxious sound.

The dancers, in variations of partnering, including intervals of two men, as well as men and women, responded to the music as though it were sending shocks and electric volts through their bodies. Particularly this was conveyed in sweeping arm movements and fluttering hands. The partnering was more frenetic and Uneven than romantic and sensual.

There were occasions when we saw two partners on either side of the stage performing similar but different, arguably Uneven, movements. There was a restive ambiance that was uncomfortable but visually arresting for the audience. We were attentive to the athleticism and discipline of the dancers but the sum total of the experience evoked more appreciation and respect than pleasure. It was a performance that provided an off setting and, ah yes, Uneven experience. Perhaps I am being too literal.

When the curtain parted for the second piece Stamping Ground we contemplated at the back of the stage a curtain of metallic, silvery, ribbons. We observed a pair of hands poking through. As would happen often during the dance there were ripples of laughter.

A woman appeared and in utter silence performed movements that seemed derived from African rituals using the whole body, particularly arms and hands. In silhouette to the audience she executed a series of hip thrusting, undulating movements that suggested copulation with an unseen partner.

After a mesmerizing interval another dancer, a man, arrived and seemingly nudged her off stage. This led to another solo and variations of the primitivist, ritualistic movements of the first soloist. Much of this was so exaggerated and strange that some in the audience began to laugh. This was sustained by a boy who could be heard throughout the performance which apparently struck him as meant to be funny.

As another and another dancer came on stage for more and more solo sequences we did indeed wonder about how best to respond. Was this intended as an amusing comedy or a display of inventive movements?

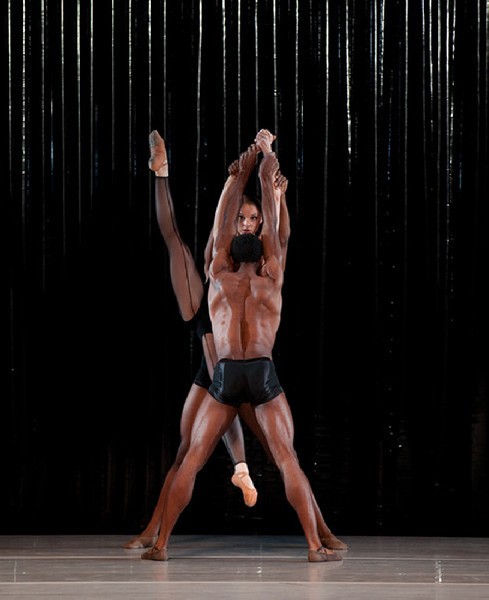

There were remarkable contortionist elements. Two male dancers, with chiseled, sculptural bodies and arms that extended out forever and ever, assumed the kind of convoluted poses and gestures that one might find in a performance by Pilobolus. In a crouching posture front became back and back front as hands waved at us from anatomically impossible vantage points. Was it fascinating or just gimmicky?

The only sound we heard entailed feet stomping on the ground or hands slapping the body. In that regard the dancers provided the music.

A female dancer performed tricks with two male dancers. On either side in silhouette they lifted her straight, vertical, inverted body. She was swung back and forth simulating a clock’s pendulum. The men were crouched over. When she jumped on the back of one male the other fell to the floor in an apparent chain reaction.

Later in the sequence she killed them. There were many references to animals and the hunts. Prey vs. predator. When they fell dead on the stage she exited through the curtain. They remained “dead” on the stage. After an interval unseen hands dragged them behind the mirrored curtain. The audience laughed.

About mid way through the piece we heard the percussion kick in with a range from small bells and snares to crackling kettle drums. At this point the six soloists reappeared as an ensemble with more extended and complex variations of the themes and movements initiated in the solos.

Driving home last night I ran the notion of originality through my mind. Just how important is that to the sense of impact and progress in contemporary art? Even though Stamping Ground had been created in 1983 the work was new and surprising to me. Perhaps in the dance world its premise has become a cliché. How important is it for audiences to keep up with changes in the arts> What does the newness of a work mean three decades later? Was it prescient for its time or am I just slow to catch up?

That implies an intimidation factor. If you don’t get it, then you are, perhaps, ignorant or conservative. If overly enthusiastic perhaps one is just a patsy and not tough enough. The easiest and safest approach is to praise what you don’t understand.

During intermission I chatted with the elderly man seated in front of me. He and his wife have been Pillow subscribers for decades. I asked for his opinion of the work “Calisthenics” he said. “And way too long.” Then he added. “But I’m not a critic.” To which I responded “I am.”

Or am I? More and more I wonder about that for two reasons. The challenge of writing about new and difficult work. And, the era we live in where everyone, but everyone, is a critic. So the opinions of those who have spent their life looking at and evaluating works of art are measured against anyone posting an opinion on Facebook or Twitter.

Accepting the role of writing about the arts is entirely different than just sitting in the audience, enjoying a performance, and perhaps posting an on line comment. Often it is more work than pleasure. While enjoying a performance the critic is disrupted by trying to find its content, form, and shape. There is a vocabulary of terms, gestures, movements, and patterns that take a lifetime to learn and use in context.

The final work Red Sweet, for example, with a Baroque score of Vivaldi and Biber, seemed to be a playful evocation of classical ballet as well as wry riffs on those impressions and assumptions.

It is a trope contemporary dance for companies to set works to Baroque scores. It conveys to the audience a paradigm of ballet. The music assures us that we are seeing a work within the classical traditions that audiences love and respond to. That leaves the choreographer with an either or decision.

One option is to play it straight and conform to the beauty evoked by the score, delivering on its expectations. The other approach is to create variations and break it down with elements of irony and humor. We call that a deconstruction.

What we observed in Red Sweet seemed to hover between those polarities. Now and then were segments lifted from ballets by Tchaikovsky. But at the end of classical elements would come something unanticipated. One might simplify this as a dialogue between the classical and the anticlassical or post modernist. The boundaries between tendencies were so subdued and submerged in the overall flow of the dance that it was not one or the other. One did not know whether to laugh or cry.

Which is a metaphor for the experience of the Aspen Santa Fe Ballet. It was a rich and satisfying evening of contemporary dance but you came away with no signature of the experience. On another occasion you might see a different program by the company and emerge with another set of impressions. It is a motive to want to see them again and again.

In a climate of branding and marketing, however, lacking an identifiable signature may be a fatal flaw. Particularly when on the road visiting world class dance venues such as Jacob’s Pillow.