Scott and Hem in the Garden of Allah

Barrington Stage Co-Premiere by Mark St. Germain

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 22, 2013

Scott and Hem in the Garden of Allah

By Mark St. Germain

Directed by Mark St. Germain

Scenic Design, David M. Barber; Costumes, Margaret A. McKowen; Lighting, Scott Pinkney; Sound, Jessica Paz; Fight Choreographer, Ryan Winkles; Production Stage Manager, Lori M. Doyle

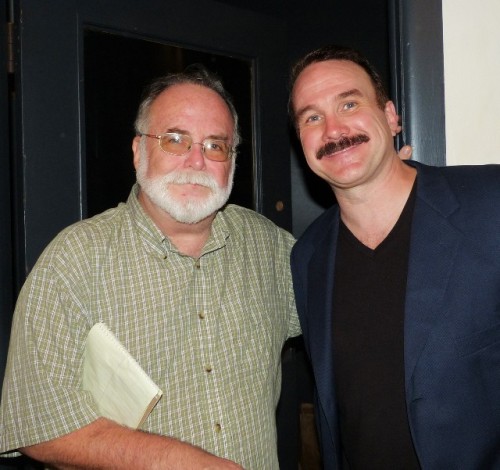

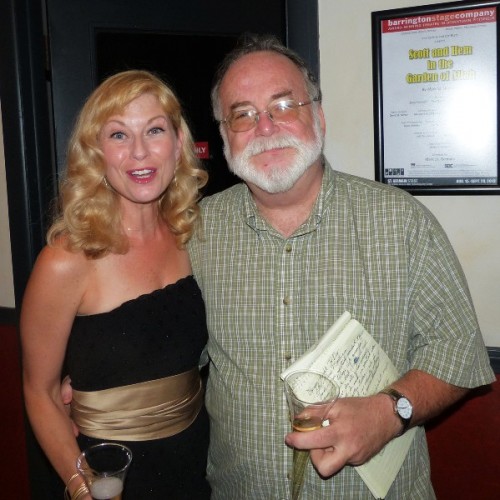

Cast: Joey Collins (F. Scott Fitzgerald), Ted Koch (Ernest Hemingway), Angela Pierce (Miss Evelyn Montaigne), Mary Louise Wilson (voice of Dorothy Parker)

Barrington Stage Company

St. Germain Stage

August 15-September 29

Co-Production with Contemporary American Theatre Festival in Shepherdstown, West Virginia where the commissioned play premiered in July.

Combined royalties for all of his published works earned a meager $13.13 in 1937. Today F. Scott Fitzgerald is remembered primarily for a single novel The Great Gatsby. He got a job adapting novels into scripts for the then decent pay of $1,000 a week.

During the Roaring Twenties as a member of what Gertrude Stein dubbed The Lost Generation he and the legendary Zelda, with their daughter Scottie, lived the Parisian high life in the circle of the well heeled ex-pats Gerald and Sarah Murphy. Fitzgerald was the highest paid, magazine short story writer of his generation.

His greatest personal and literary, friend/ rival was the womanizing, bullying, mean drunk Ernest Hemingway. A major difference is that, unlike the Fitzgeralds, he was better at holding his liquor. Zelda was taken with jumping into fountains and off of balconies while Scott often acted the drunken fool.

When you are young, rich, and fabulous that behavior and lifestyle is the tolerable stuff of gossip woven into legends. But there is nothing more boorish than a morose old drunk, down on his luck, burdened with debt and responsibilities.

The late Fitzgerald as a literary whore for the studios is a fascinating, macabre and melancholy study of the utter decline and humiliation of an author who defined the glamour and glitz of the Jazz Age. His persona and literary style were unsuited to the decades of Depression and War which followed.

Working as a hack for the studios Scott was a shattered shadow of his former self. He found some refuge with Shelia Graham the gossip columnist who loved and nurtured him. For squandering the gift of genius Scott was burdened with paying to keep Zelda in an asylum (where she died in a fire) and Scottie in a prep school. Actually, the Murphys helped to pay that bill.

In Mark St. Germain’s play Scott and Hem in the Garden of Allah, which he has written and directed, Scott is past deadline for a script adapted from Erich Maria Remarque’s novel Three Comrades. While Remarque wrote the masterpiece All Quiet on the Western Front his other novels were mediocre. The film is in production and Scott is struggling to provide dialogue.

Studio head Louis B. Mayer has assigned an assistant, Miss Evelyn Montaigne (Angela Pierce), to keep Scott (Joey Collins) on schedule and off the sauce. Scott has been sober all of nine days. In a key plot point Miss Montaigne has been sober for some sixteen months. She is crafty at searching the apartment, in the legendary Garden of Allah, West Hollywood complex for hidden stashes of booze.

It’s the Fourth of July, 1937 and from the balcony of the apartment, efficiently designed by David M. Barber with lighting by Scott Pinkney, we hear a raucous celebration around the pool below. It seems that Tallulah (Bankhead) is cavorting about naked and Dorothy Parker (the off stage voice of Mary Louise Wilson) calls to him to join the fun. Scott comments on the spectacle of Charles Laughton once floating in the pool wearing his Quasimodo costume.

But Scott is pressed by a midnight deadline. Miss Montaigne will have none of the revelry and noise that disturbs his ability to work. She yells below for them to pipe down. They ignore her until she announces that she works for Mr. Mayer. Silence ensues and her first of many well deserved laughs in a stunningly, noirish performance. In appearance and manner she is wonderfully of the period as a woman in a man’s world trying to establish a career in Hollywood. Her future is entirely linked to keeping Scott in line.

There is a knock at the door and she opens it to see an uninvited stranger. There are protests that Mr. Fitzgerald is busy. The stranger assures her that Scott will want to see him. With bravura he identifies himself as Ernest Hemingway (Ted Koch). Oh, it’s you, seems to be her cool response. Deflating his enormous ego she continued not to get his right name.

“He’s writing. And he’s on deadline” she says. “I know the drill; I’m a writer too.” “Really what have you written?” He responds “The Sun Also Rises, To Have and Have Not, A Farwell to Arms.” She counters “Ben Glazer and Oliver Garret wrote A Farewell to Arms.” Testy he responds “They wrote the screenplay. I wrote the book.” She shot back “The movie made a million two. How much did your book make?”

Yah gottah love that gal. She surely has all the best lines delivered with devastating wit and timing. She keeps the randy bully boys in their place.

Scott and Hem? Well. They are both such losers that it is tough to feel for either of them.

The Barrington production has come a long way from what we saw in Shepherdstown. The cast was simultaneously rehearsing and performing in a second production. The performance of Collins was forced and Hemingway not what one would have hoped for. The casting was entirely decided by the festival’s artistic director, Ed Herendeen.

Having more time and focus in Pittsfield has made a huge difference. Many of the initial objections to the performance of Collins have been addressed. In Shepherdstown I found his inflection too British and Oxfordian. Since then I have listened to recordings of Fitzgerald reciting. His vocal style was indeed, shall we say, Princetonian. Collins has now mastered and subdued his Fitzgerald into a far more compelling and naturalistic delivery. We found ourselves more ensnared by his melancholia.

The Hemingway of Ted Koch is more convincing both in a physical resemblance as well as an ability to entice and provoke Fitzgerald. Koch is measured and sure in revealing flashes of Hemingway’s vulnerability and eventual descent into madness and suicide. As this more evolved production reveals Hemingway, for all of his drunken bluster and worldly success, was even more dark and troubled than the fragile and shattered Fitzgerald.

They were both alcoholics but Hemingway was in denial. During the course of the boozy and brawling encounter Hemingway polishes off two pints of hooch. During which Scott sucks on Coke with a dash of maple sugar. Out of booze Hemingway demands that Scott deliver that hidden bottle which the eagle eyed Miss Montaigne has not mananaged to uncover.

It helps to bring to the play a deep reading of their works as well as biographies. To truly understand what’s going on and the fourth, unseen, and perhaps most important character, Zelda, it’s essential to read her failed novel Save Me the Waltz and the magnificent biography Zelda by Nancy Mitford.

Since Shepherdstown the dialogue between them about Zelda has been sharpened as the flash point that brings them to blows. Toward the end of the play it provokes Scott into a shouting match about rumors that he stole from Zelda’s diaries. In a stunning reversal from the meek and seemingly beaten man we find him fighting for his identity and literary legacy. It long has been argued that Zelda was more than his muse. And that Scott cannibalized their friends, like the Murphys, as characters in novels and stories like Tender Is the Night.

Hemingway came to Hollywood in 1937 to promote his documentary film The Spanish Earth (narrated by Orson Welles) and participate in a benefit to raise money for ambulances and war relief. It is plausible that the old friends met on that occasion.

During that Hollywood visit Hemingway arrived unannounced. There is a complex agenda beyond meeting and discussing old times. He taunts Scott about not writing novels. He just needs money to have the time and resources to work. There is an offer to sell the film rights to Snows of Kilimanjaro for a dollar. It’s a suspiciously generous offer.

Compounded by the crushing revelation that the studio is routinely rewriting his scripts. He taunts that Scott is the only person in Hollywood who doesn’t know this. It was the standard procedure for film studios.

Actually, Fitzgerald did work on a final novel The Last Tycoon. The unfinished manuscript was edited and published posthumously by Edmund Wilson in 1941.

There’s a hitch to the deal. Hemingway allegedly is writing a book on a decline into madness. He wants to model it on Zelda. That’s the pound of flesh he demands. Initially, Scott is tempted and starts to reveal details. Eventually it surfaces that it is really about Hemingway’s own fears of impending madness. He is writing a novel about himself.

Consider the family history. Hemingway’s father blew his head off with a shot gun. Recently, his mother has given him that gun which eventually he used to turn his head into spaghetti.

We learn of an evil mother who kept him in dresses and curls until he was five. We are offered glimpses of his own sexual misgivings as well as those of his son who liked to cross dress. Hemingway wonders if his own sexual confusion has been passed along genetically like the mental illness of his father.

This is tough stuff in a truly disturbing and disquieting, but powerful and riveting evening of nail biting theatre. St. Germain has taken us down the rabbit hole into the darkest recesses of the Faustian cost of squandered genius. It is no surprise that after such a cathartic meeting Scott and Miss Montaigne are back on the bottle. Nobody lives happily ever after.

The morning after an evening of devastating drama I’m trying to settle my nerves and recover from a theatrical hangover.

Interview with Mark St. Germain