What Joe Thompson Means to Northern Berkshire County

The Daunting Legacy of MASS MoCA

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 22, 2020

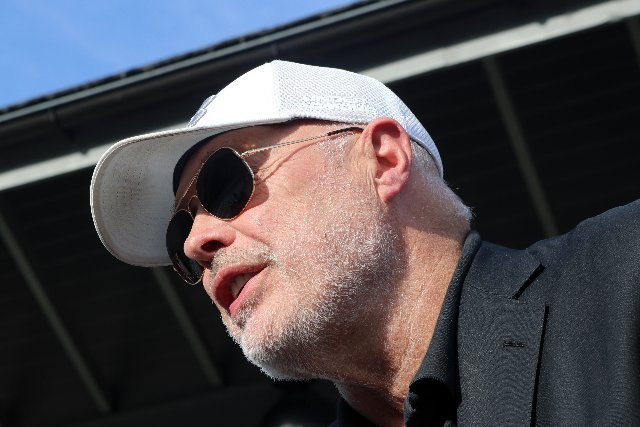

Joe Thompson has announced plans to step down as director of MASS MoCA in October. He will stay on as a consultant to the board with loose ends to tie up. By summer of 2021 he will sever all ties.

As an undergraduate at Williams College, class of 1981, in the senior year he loaded up on fine arts classes and graduated with a double major of fine arts and economics. He went on to earn a MBA from the Wharton School of Business.

During a visit to campus he connected with a former professor, Tom Krens, then director of the Williams College of Art. He was hired as a museum preparator. Krens was in the early stage of developing the 17-acre former Sprague Electric campus in neighboring North Adams. It eventually became Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA).

On assignment for Art News I met with Krens for lunch in Williamstown. With an enormous roll of keys, we then toured a number of structurally sound but abandoned and run down, 19th century, brick buildings.

When King Cotton ruled North Adams had mills that spun thread and wove cloth. It then went to be printed by Arnold Print Works. The cotton industry literally went south, following the 1913 Paterson New Jersey Strike. North Adams got a reprieve when the campus was converted to Sprague Electric. Elders in town remember when there were three shifts per day at Sprague particularly during the war years.

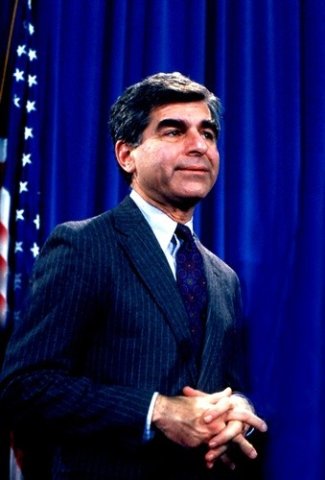

When Sprague closed, the Northern Berkshires became one of the most economically depressed regions of the Commonwealth. That was the 1987-88 pitch of Krens to Governor Michael Dukakis. Signing the MASS MoCA bill was one of his last acts in office. When he was followed by Republican Bill Weld, the oft quoted response was “Over my dead body.”

By then Krens had departed to take his visionary concepts to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum from which he developed franchises. The North Adams project was passed to Thompson. The development director of the original team was Jennifer Trainer. They married but later divorced. For the last few years, Trainer-Thompson has been the director of the Hancock Shaker Village and the author of a number of books.

With a skeleton crew and facing dauting challenges construction began in 1996-1997 with a 1999 opening. It was launched with some 200,000 square feet of exhibition space.

As Thompson told me in one of a number of interviews “One thing that a lot of people don’t realize is that we opened in 1999 with a little over 200,000 square feet of this complex developed. The total footprint of developable space is about 600,000 square feet on 17 acres. I guess if we count the R&D of the space we acquired across the street, which is now a Court House, it is closer to 650,000 square feet. When we inherited the buildings there was about 780,000 square feet. We took down a couple of buildings which were falling apart. Leaving all told, I’ll count across the street, about 650,000 square feet.”

With a lot of real estate under its control a portion was developed as income generating retail space. “From 2000 to 2006” he said “We added commercial space. Building One was the first we did. Then Building Two where Storey Publishing is located. (The company employs 50.) Then Building 13 where Donovan & O’Connor (a legal firm) and our other tenants are. On the Marshall street lot which is a major addition. Then we picked up the Court and Social Security building across the street which we bought. We purchased that from Sprague Technologies. That was not a part of the original deal. We borrowed money and renovated it as the Court House and the same thing with the Social Security offices. As commercial real estate development. We currently (2012) earn $1.5 million in income from tenants.”

From a MoCA press release regarding Thompson’s pending departure.

“During Thompson’s tenure, the institution hosted more than 10,000 artists, working across all media. Annual visitation has grown from 60,000 in the early years of the museum, to 300,000 per year (pre-COVID), close to 25 times the population of its hometown. The developed footprint of the 24-building factory campus has grown from 200,000 square feet in five buildings, to 550,000 square feet in 17 buildings, making MASS MoCA the largest institution in the United States devoted to new art.

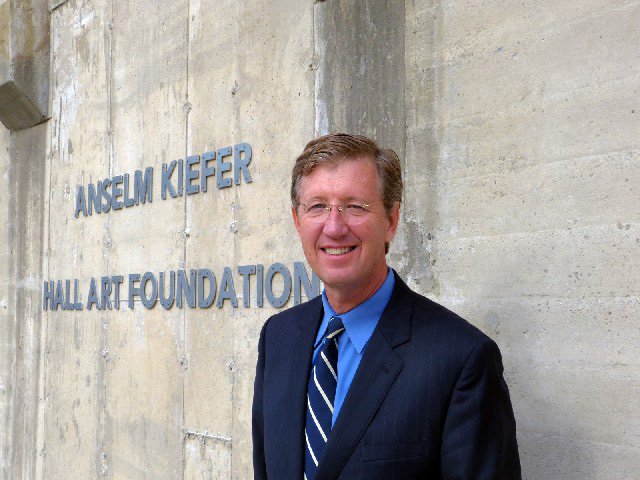

“An inventive model of long-term partnerships pioneered by Thompson in collaboration with a host of fellow curators, lending institutions and artists has featured landmark retrospectives, major installations, and changing exhibitions including those by Sol LeWitt (co-organized with the Yale University Art Gallery and the Williams College Museum of Art with loans of 25 years from over 50 lenders), Laurie Anderson, Jenny Holzer, Anselm Kiefer (co-organized with the Hall Art Foundation with a loan of 15 years), and James Turrell (whose major 25-year retrospective installation includes examples from all seven decades of his career, and every major category of his work on loan for 25 years). Artists who have had important exhibitions or long-term installations at MASS MoCA include Ann Hamilton, Nari Ward, Xu Bing, Robert Wilson, Sanford Biggers, Cai Guo-Qiang, Mona Hatoum, Tim Hawkinson, Spencer Finch, Annie Lennox, Natasha Bowdoin, Martin Puryear, and Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle. Under Thompson’s leadership, MASS MoCA has become a premier concert venue in the Northeast, featuring performances by both well-known and rising stars, including Beck, Benjamin Clementine, Annie Lennox, The Pretenders, The National, Patti Smith, Maggie Rogers, Sinkane, Dr. John, Flying Lotus, Car Seat Headrest, Vampire Weekend, Adia Victoria, and George Clinton.

“Thompson and his colleagues in performing arts have also nurtured a robust artist residency program at MASS MoCA, which has workshopped major new projects and experimental works-in-progress by Bill T. Jones, William Kentridge, David Byrne, Urban Bush Women, Paola Prestini, and an annual two-week residency with Roomful of Teeth. In conjunction with David Lang, Julia Wolfe and Michael Gordon, Thompson co-founded the annual Bang on a Can Summer Music Festival. Thompson also co-produced Wilco’s Solid Sound Festival of Art + Music with Jeff Tweedy and Alex Crothers, and co-produced FreshGrass, an annual festival of American roots and alt-folk music with Chris Wadsworth. Thompson conceived a children’s education facility and in-classroom program called Kidspace, with the Clark Art Institute and Williams College Museum of Art, which has now grown into an innovative education department serving adults, children and social service agencies across the Berkshires.

“At the time the museum was conceived, North Adams’ unemployment rate approached 20%, 7 times higher than the Massachusetts state average. By 2019, pre-COVID local unemployment had fallen to 6.4%, or about 1.4 times the Massachusetts state average. By 2019 the museum itself sparked $52 million in new economic activity every year (and over $700 million cumulatively, including investments in buildings and infrastructure), totaling many times the state’s public investment of $60 million over 20 years.”

The original concept of Krens was that MoCA would become a warehouse for collections of minimal art. To illustrate that concept, before the museum opened, there was the demonstration installation of works by the Italian artist Mario Merz. These works would require basic infrastructure and no costly climate control. Those approaches were developed at DIA Beacon and Donald Judd’s Chinati Foundation on a former Air Force base at Marfa, Texas.

The current paradigm of MoCA includes some of that approach. The most recent wing includes 25-year-long installations by blue chip artists. There are also buildings for sustained installations by Sol LeWitt and Anselm Kiefer.

There are also changing exhibitions including year long installations in Building Five, the length of two football fields, in a vaulted space. It is the rotating program that lures back visitors year-after-year. Some of these displays have been spectacular while many underwhelmed. That is the general challenge of contemporary art.

In addition to the status of the semi-permanent collection there is always something fresh and compelling to deal with.

Strategically, the museum has broadened its reach with a varied menu of the performing arts. Wilco’s Solid Sound and the annual Fresh Grass festivals have swamped North Adams with visitors selling out local hotels and camp grounds.

Overall, MoCA has put a lot into the local economy but as critics note, more by default than design. Attracted to the area by MoCA and the arts many artists have bought lofts and refurbished affordable housing. Other than just being there MoCA has done little to support the growing community of artists. Thompson and MoCA curators rarely if ever attend artists openings or have direct knowledge of what is being created within a 50 mile radius. Occasionally a “local” artist is curated into a MoCA show but there is no strategy to support the creative community.

The vast majority of countless projects with the museum’s superb curatorial and installation staff have been executed flawlessly.

A project in 2006 with Christoph Büchel “Training Ground for Democrcy,” curated by Nato Thompson, was terribly wrong and went into litigation

Early on the artist stated “When you work with a curator in Germany, the artist will yell at the curator and stomp off, and the curator will do the same…This is the way things are done in a different culture."

Running over budget with no end in sight, the artist made unreasonable demands which the museum made every effort to comply with. That included creating an enormous entrance to the gallery from a courtyard to enable fork lifting in massive found materials. The project never opened but included: A 35-foot oil tanker, a two-story house, a carousel of bombs, and an old movie theater, rebuilt down to its water-stained ceiling tiles.

As a work in progress, Thompson led VIP groups through the space. An account of that experience was posted in Berkshire Fine Arts. It became a document in the artist’s suit against the museum for violating the artist’s rights to only allowing the finished work to be viewed.

Much of the art media sided with the artist. The director and curator were faulted for not having a firm contract and budget. It is arguable that subsequent projects had appropriate paper work.

For the status of the museum, and morale of the staff, this was a MoCA lowpoint. The court ruled that the museum could open the exhibition even if incomplete in the view of the artist. No doubt the publicity would have generated considerable attendance. The museum opted to deinstall and, in every sense, an ambitious and interesting project went into the bin. It was soon replaced by a superb Jenny Holzer installation that brought MoCA back from the brink.

Triumphs were to follow. Including building out and installing to near capacity.

The past year, however, has marked both institutional and personal setbacks.

In February COVID-19 shuttered the arts in America including MoCA. That has meant lost revenue and staff reductions. The museum has reopened with appropriate safety precautions. We visited recently to view and review (for Boston’s Arts Fuse) the new exhibitions. During high season the museum is functioning at a fraction of capacity.

As WAMC reported “On July 20th, 2018, a car Thompson was driving in North Adams collided with local motorcyclist Steven Fortier, 49, who was killed. Now, almost a year later, Thompson is set to be arraigned on a misdemeanor charge of motor vehicle homicide by negligent operation – as well as a marked lanes violation – in Northern Berkshire District Court on June 19th. The misdemeanor carries a maximum penalty of two and half years behind bars.

“North Adams Police Chief Jason Wood told WAMC that after a May 9th hearing, the court found that there was ‘probable cause to issue a complaint.’ He confirmed that the investigation found that alcohol was ‘not a factor’ for Thompson in the crash.”

It is a matter for the courts to decide. But in addition to the pandemic this has been something else to deal with. The work in North Adams has been all but completed and remarkably so. There is time between now and next summer to plan the next move.

From undergraduate days at Williams College to now, his roots are deeply planted in Northern Berkshire County. In his early 60s, he would be a prime candidate to head either a major museum or one in development. He has the option to stay here and work as a consultant/ developer in the arts and entertainment.

Focus now turns to MoCA post COVID. That will take time, and arguably no cultural institution will be the same for a very long time. Part of that change may well and properly entail stronger bonds with the ever expanding creative community that surrounds the museum.