Schumann's Rare Opera

Forgotten masterpiece brought to life

By: Michael Miller - Aug 24, 2006

Robert Schumann, "Genoveva," Bard College Summerscape, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York; The American Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Leon Botstein, music director; directed by Kasper Bech Holten; Christian Lemmertz, designer; Ylva Kihlberg, soprano; Philippe Castagner, tenor, Johannes Mannov, baritone, et. al.Each July and August since 2003 Bard College—under the direction of its president, conductor and musicologist Leon Botstein—presents Summerscape, a rich offering of all the performing arts: classical music, jazz, opera, operetta, cabaret, dance, and theater, barely more than an hour west of Great Barrington. For the classical music lover, the climax is the Bard Music Festival, founded in 1990, a series of concerts and conferences devoted to the work and the cultural context of a single composer over the course of two August weekends and a third in the autumn. A special effort is made to tie the other presentations in with these programs, above all the opera.

This year the composer is Franz Liszt, who is as much an icon of the nineteenth century as his son-in-law Richard Wagner. Not only a composer, but also a virtuoso pianist, a conductor, teacher, and critic, Liszt was deeply engaged in all forms of European culture: literature, theater, politics, national movements and folk traditions, the visual arts, and religion—an ideal subject for a far-ranging project of this sort. Before reporting on "Liszt and his World" itself, however, I'll discuss the opera, Robert Schumann's rarely performed "Genoveva," here given its first staged production in North America, under the direction of Kasper Bech Holten, who, at thirty-three, has already attracted much attention for his production of Wagner's Ring Cycle at the Royal Danish Opera in Copenhagen, of which he is the director. "Genoveva" was chosen because Liszt, as court conductor in Weimar, performed it in 1855, a year before Schumann's death, and stated that he believed it to be the best recent opera by any composer other than Wagner, a sincere conviction maintained in spite of Liszt's rather troubled relations with Schumann and his wife Clara, who resented his free-wheeling behavior and his opinion that Schumann's music was for the most part conservative and perhaps somewhat provincial and bourgeois ("Leipzigerisch"). Liszt most valued Schumann's theatrical work, the "Faust Scenes" even more than "Genoveva"—the very aspect of his work which was least familiar to subsequent generations.

Composed in the revolutionary year 1848, "Genoveva" got off to a bad start at its première in Leipzig two years later, partly because a series of postponements pushed it well beyond the usual season, partly because of a defective performance under Schumann's own direction, and partly because the composer had taken great pains to achieve something new and entirely characteristic of his personality and his theory of what German opera should be—something beyond the immediate comprehension of his audience and the critics. After that, "Genoveva" slipped out of the repertory and became an obscure legend in the history of music: Schumann's only opera, a failure (according to the received opinion) because of the composer's poor sense of drama and its crude libretto, bereft of psychological development or even believable characters, not to mention its lack of melodies. However, "Genoveva" has been slowly growing a following among musicians and musicologists over the past generation, and certain prominent figures like the conductor Nikolaus Harnoncourt and the Schumann biographer, John Daverio, have shown a real passion for it. Its moment appears to have come just in time for the hundred fiftieth anniversary of Robert Schumann's miserable death in a mental asylum. For Harnoncourt, the lack of psychological motivation is what gives it a contemporary, almost absurdist appeal.

This was not what Schumann was striving to achieve at all, nor is it what Holten, working with set designer Christian Lemmerz, is trying to discover in the work. Holten, who has said that "opera is about trying to make people cry. The opera house should be the emotional fitness-center of society—a place where you go to exercise your love-muscles, your hate-muscles and all the others as well..." is looking precisely for this psychological dramatic marrow.

Schumann knew that he needed to write a successful to establish himself in the top ranks. Encouraged by the ambitious Clara, he had planned to write an opera for years (Still in his teens, he dreamed of writing on opera on Hamlet.), and his work as a music critic had given him ample opportunity to formulate just how he should go about it. Beginning with the principle that opera should edify before it entertained (He detested Meyerbeer and his Parisian grand opera, which was all the rage in Europe.), Schumann became committed to the idea of a literary opera, a drama based on the best literary sources, for example Shakespeare, Calderón, or perhaps Boccaccio, and aiming to do justice to the original texts. In the process, crowd-pleasing spectacle and tuneful set-pieces should be curtailed, if not eliminated, in favor of dramatic music, which flowed on without interruption, following the action on the stage and the psychological processes of the actors—a method familiar enough today from works like Strauss' "Elektra," and Berg's "Wozzeck." After considering some fifty different subjects, Schumann settled on the legend of St. Geneviève, fascinated by Friedrich Hebbel's unperformed 1843 play, a subject which had already been rejected by other composers, largely because of the heroine's passivity. After dismissing his librettist and seeking the help of Hebbel himself, Schumann, adapted the play largely by himself, bringing in some elements from an earlier treatment by Ludwig Tieck, the Shakespeare translator.

What is the story? Genoveva has just married the Count Palatine Siegfried, who is promptly summoned by Charles Martel to fight the infidel in France. He leaves her and his castle in the care of Golo, an artistic and reflective man (sung by a lyric tenor, not the usual villainous baritone), who resents being deprived of the opportunity to show his valor, as well as the responsibility of protecting a woman whom he desires. Encouraged by his old nurse, the witch Margaretha, he attempts to seduce Genoveva in her bedroom. Shocked, she calls him a "dishonorable bastard," which pricks his deepest insecurity. His love turns instantly to hate. With Margaretha's help he convinces people in the castle that she is having an affair with Siegfried's trusted servant, Drago, who is promptly lynched. Genoveva herself is to be taken to a deserted place and beheaded. Meanwhile they learn that Siegfried, wounded in a victorious battle, is on his way home. Margaretha rushes to intercept and poison him. Failing that, she attempts to delude him with her magic mirror, but he arrives home in time to get the truth out of Margaretha and pardon Genoveva, who has thus far been preserved by her faith in the Blessed Virgin Mary and the Holy Cross, while Golo commits suicide.

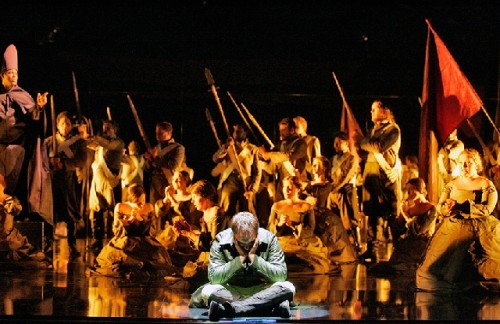

In the Bard production Holten makes no attempt to invoke realism of any kind, least of all in the liberal splashes of stage blood which provoked laughter perhaps a little too often—inopportunely, I think, in Golo's suicide. Rather, he exploits the opera's surreal fairy tale air and Genoveva's child-like qualities to penetrate to its psychologically compelling core. Mirrors are present throughout the opera, not only to give the sets and the chorus the impression of being larger than they really are and to provide Margaretha with her necessary prop at the appropriate juncture, but to make the action unfold in a symbolic hall of mirrors. As her last attempt to deceive Siegfried fails, the mirror is shattered in an effect recalling the fun house scene of Welles' "The Lady from Shanghai." A verbal motiv, the word "krank" (sick), crucial for the characters as well as the composer's own battle with mental illness, resounds emphatically on repeated occasions. In Schumann's score, many of the most dramatic moments unfold in the intimacy of a pianissimo, especially the key moment in Holten's interpretation, the chilling bars when Genoveva insults Golo, and his love is transformed into hate. Golo is older than Genoveva, but unstable, emotionally and morally sick from love, and Holten and the excellent singing actors bring this moment home with full effect, convincing as a disastrous moment between young, vulnerable people. At other times Holten resorts to exaggeration and even burlesque to bring the opera to life for us. Schumann's text and music are not without hints that Golo's passion for Genoveva may not be entirely unrequited. Holten brings this into the foreground, undercutting Schumann's triumphant final chorus with her regretful fascination with Golo's corpse. Siegfried is a seasoned fighting man but not much else and was in fact described by a contemporary critic as a "Dummkopf." He earns our sympathy in his sickbed scene, in which Margaretha continues her fruitless attempts to undermine his hardy constitution with poison. Holten approaches this with broad comedy, and however much his sight gags went a bit far at times, they succeeded nonetheless. The loyal but ugly Drago is made to look clownish even for the Polonius figure he is, later transformed by Mr. Lemmerz into an horrific ghost, rather an avenging angel. Holten's sudden and surreal shifts from sentiment to gallows humor and his refusal to sidestep any of the more egregious artificialities of the plot provide us with an entertainment which is both enlightening and chic, as we listen to Schumann's beautiful score unfold its drama.

The youthful international cast, superb singers and gifted actors, negotiated Schumann's complex, asymmetrical vocal lines, showing a gift for bringing Schumann's Lied style together with opera, and performing as a responsive ensemble, something we see all too rarely on American operatic stages. Johannes Mannov as Siegfried, Philippe Castagner as Golo, Joshua Winograde as Drago, Michaela Martens as Margaretha, and Ylva Kihlberg as Genoveva all gave their parts the vocal elegance and intelligent characterization they required. Leon Botstein and the American Symphony Orchestra allowed the score all its Romantic breadth and weight, while making the most of the bizarre tone colors and harmonic progressions associated not only with the villains, but also with the more extreme emotions of the protagonists. Mr. Botstein managed to balance a rich string sound, clarity in Schumann's complex textures, accurate rhythms, and a sweeping forward line. I was already under the spell of Schumann's extraordinary opera when I came to see this production, and I was thrilled to have the rare opportunity to see it on stage. Still, I can't quite imagine it as a staple at the Met. We can only be grateful that Mr. Botstein and his summer festival can provide a venue for a connoisseur's opera like "Genoveva," where Mr. Holten's theatrical brilliance can persuade us that yesterday's lunatic can become the psychological genius of the present day.