Seneca Artist Peter Jemison

Raising $9 million for Ganondagan

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 24, 2006

Recently we traveled to Victor, near Rochester in upstate New York to attend a weekend long festival of dance, music and culture at Ganondagan a 569 acre Historic Site and ancient home of the Seneca Nation. For the past year I had been in phone and e mail contact with its director, Peter Jemison, a member of the Heron Clan of the Seneca. Several months ago he came to dinner when passing through Boston on business. We were actually getting reacquainted as we had met through a mutual friend, Raeford Liles, during the 1960s in New York City But as we soon found out during the festival, he had warned us that there would be little time for socializing. He was constantly on stage introducing the various acts, keeping the audience amused when acts were as much as a half hour late. It was amazing to see how effortlessly he conveyed to the audience the history of Ganondagan which was formerly a village with 150 long houses each holding extended families of 40 to 50 individuals. It was attacked by the French in 1687. During the French and Indian War the Seneca supported the British and were raided by the French army. In 1779 under orders from George Washington, during the Sullivan Clinton Campaign, some 40 mostly Seneca settlements were attacked including present day Geneva, Canandaigua and several in the Genesee River valley. Ganondagan was probably then unoccupied.The hostilities occurred during harvest time and the survivors tried to salvage burned corn which led to the recipe for roasted corn soup that was being served during the festival along with tasty bear and deer sausages.

As to the metaphorical aspect of wearing many hats he is constantly juggling a life that finds him scrambling for time in the studio where he makes landscape paintings, drawings and decorates paper bags. In 2002 he worked with his sons to create a video "Wiping Away the Tears" which has been widely circulated in museum exhibitions. He also runs the Ganondagan site as a full time job, mentors younger artists, lectures widely and was elected to the board of the Association of American Museums in 2004 to a three year term. In 2003 he was presented with an Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts by the State University of New York in Buffalo. Walking through the Broadway-Lafayette Subway Station in Manhattan I recently encountered a large Tile piece he executed in 1998 with the artist Mel Chin.

His primary focus is on developing and maintaining the 569 acre Ganondagan site. A part of the land was purchased by the state of New York in 1964 and declared a national landmark. At the time it was a plot of some 200 plus acres of farm land and there was talk of turning it into some kind of development. In July, 1687 the village was attacked by the French. It was then the largest of three nearby Seneca towns with a population of some 4,500. The raid killed 80 people. A single replica of the original, 150 long houses has been built. It is 65' long, 20' wide and 22' tall. Currently it is the primary attraction, along with nature trails. Peter was appointed site manager in 1985 and Ganondagan opened to the public in 1987.

"At the time there was an efflorescence of native culture," Peter recalled. Oxendine was a leader and activist and the space was devoted to showing the best available native work. "There was a major theatre group the Native American Theatre Ensemble and they were getting reviews in the New York Times. There were a lot of natives living in New York at the time but also divisive local politics. Since I just came for weekends I didn't want to pick sides. I would hear different versions of the arguments but would say just leave me out of it. What I wanted was to be able to say hello to everyone. When I came to New York Lloyd's couch was my landing spot. Eventually he gave me the chance to curate a show of Iroquois artists and helped to get a grant to fund it. I went to all of our communities and asked 'Who are the best artists?' The show then traveled to those communities, mostly shown in libraries, and the purpose was to inspire young people. When I borrowed the work I arranged for rental fees to the artists or bought the work. From 1974-75 I found a way to travel the work which was shown at six venues as well as Lloyd's gallery." By 1978 he moved to New York and ran the gallery program of the American Indian Community House. "I was an ironworker in the summer when I was attending Buffalo State Collage and I went back up on the iron in 1977-78 and survived the blizzard of '77 while working outdoors. I was one of the fiercest to ever hit Buffalo and western New York." He recalls being in great shape but also having issues with anger management and drinking. He stopped drinking on New Year's Eve of 1982 He became more actively involved in native traditions and philosophy. "I've been going to the Longhouse since 1972," he recalled. "It is a philosophy that comes down from a Seneca prophet, Handsome Lake. It is a way to survive and to continue an Indian way of life. The prophesy was revealed in 1799 and I follow the Code of Handsome Lake. The biggest message is 'no alcohol.' I was raised Christian but never felt satisfied."

With so much going on during the annual festival we arranged to stay over another day and meet on a Monday. Understandably, Peter was tired when he took us to his studios, one in an out building on a farm now owned by the historic site, and the second occupying a suite of rooms in an office complex in a commercial building in downtown Rochester. There he provided us with an intensive slide presentation of his work going back to when we knew each other in New York in the 1960s. That was followed by a leisurely lunch at a Thai restaurant. . We were starving artists in those days and Raeford had the great ability and generosity to whip up gourmet meals with an electric frying pan in his cold water flat/ studio.

Speaking with other native artists, Jemison is regarded as an elder, leader, friend and mentor. He wears a lot of different hats, some of which are beautifully feathered. Actually he likes hats both literally and figuratively. On Sunday he announced to the audience that a vendor had made an offer he could not refuse as he sported a new white feathered bonnet. A single, vertical, eagle feather indicates membership in the Seneca Nation while three vertical feathers signifies a Mohawk. But on Monday morning he was wearing shades and a baseball hat.

The best thing to say about Peter, however, is that all of those hats have not given him a swelled head. Don't get me wrong, he can be sharp and righteous, particularly when guarding the rites and rituals of his people, he can give and take shots, but is also a warm and benevolent educator. There is the daunting challenge of inviting and sharing his history and culture while simultaneously protecting and preserving it. During the festival, for example, he was precise in relating to the audience that native people were performing social dances and not the ritual dances associated with seasonal ceremonies that are shared only with registered members of his nation. These ritual events, which occur during the seasons of the year, may take as much as a week or two. Beyond that he offered little information.

Actually Jemison is a famous name among the Seneca people. He is directly descended from the white woman, Mary Jemison, whose family was slaughtered. She subsequently grew up, married a warrior, Hiakato and produced children, who married among the Seneca people, leaving behind a lively account of her life among her adoptive people. Peter is an eighth generation descendant of Mary Jemison. It was only as an adult and young artist, having roughed it in the New York art world for some time, that Peter fully embraced his ancestral heritage. This also entailed the difficult challenge of learning his native language as an adult so he could fully participate in ceremonies. He is also deeply committed to sharing this heritage with his and other children of the tribe.

Currently he is in the process of raising $9 million for a 30,000 square foot visitor's center. The complex will have four galleries and house a collection of historical materials some of which resulted from excavation on the site. Later this year there are plans to announce the acquisition of a major collection of historic materials including only one of five surviving war clubs dating to the 1600s. When construction is completed by 2009 Ganondagan will be a regional resource for education programs and a destination for individuals wanting to participate in and learn about native culture. With some $5 million in hand as pledges, the project is now entering the design phase. A major press conference is being planned for the winter.

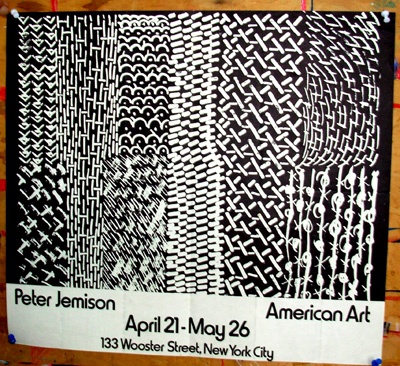

Just how does the funding break down? Some $2 million will come from the Seneca Nation which operates a casino near Niagara Fall Clearly there is a lot of work to be done in the months and years ahead. Just how did he become involved with and qualified to take on such complex arts administration? It all started when Lloyd Oxendine opened a gallery in Soho "American Art" which existed from 1971-1976. Peter was a young artist and teacher at Niskayuna, in Schenectady, New York. He would come into the city and help out in the gallery. There was a sleeping loft in the space so he could stay over and even open the gallery in the morning. He became involved in all aspects of hanging shows and managing the space. . Another $1.7 is coming from NY State. There is a private donation of some $5 million and the remainder from various sources. The site is open six months a year and eventually will operate at least eleven months. Currently Ganondagan draws 37,000 visitors at an average fee of just $5. Including Peter there is a staff of eight, full time and two half time employees. During the festival, however, there were 150 volunteers each day. The annual budget is now $580,000. Of course with increased facilities and programming there will be a need for an endowment.

In addition to curating numerous shows for the Community House he was also in contact with the artist group "Grey Canyon." The group which was largely focused in Albuquerque included Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Emmi Whitehorse, Larry Emerson, Paul Willetto and Conrad House.

"At about the same time Jaune had a one person show in New York at the Jill Kornblee Gallery," he said. "That's how I met her. She was looking for venues to travel shows. There was also George Longfish who ran a gallery program at University of California in Davis. Edgar Heap of Birds was at the Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia. The circuit of venues and shows lasted from 1978- 1985. In my program in New York I showed everyone I could find. But I didn't have any money to travel the shows. Just when I started at the Community House a woman wanted to bring a Grey Canyon show to New York. The night of the opening the show hadn't arrived. The work was stuck on a loading dock in Chicago. Some uptown woman in a fur coat arrived. Luckily we were able to put together a slide show of the work. The shipment arrived on the Monday after the opening."

After that initial fiasco things settled down and Jemison's shows over the next few years were well received including occasional reviews in the major publications including the New York Times. The gallery enjoyed a prime location in Soho opposite the OK Harris Gallery but despite that initial spark in the 1970s, an era of progress and activism, native art got subsumed by the other ever evolving interests of the art world.

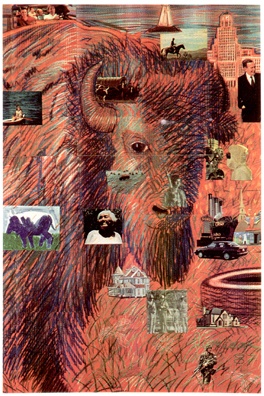

This may even describe the ebb and flow of Jemison's own work. As an emerging artist in the 1970s he showed with Oxendine's gallery and before that with the uptown Tibor de Nagy Gallery. During the slide show he presented to us the work evolved from flat, patterned abstraction to an increasing element of naturalism. Some of the most interesting and successful work involved using conventional brown paper shopping bags as a support. This allowed for working three dimensionally on several surfaces and planes simultaneously. One of the early examples was curated into the legendary, avant-garde "Times Square Show" which grouped emerging artists in an abandoned massage parlor. He continued to explore this theme which involved into making prints with hand made, and embossed paper created to retain the feel of the original bags.

Today, Peter is an active and successful artist. He explained with some humor that part of why he rents such a large studio space is to show expenses and not give all of his earnings as an artist to the IRS. As we walked through the rooms there seemed to be a number of separate studios and projects underway. A number of the works entail fairly conventional landscape views surrounding Ganondagan. There are elements of patterning that he describes as related to traditional bead work. He insists that it is the involvement with nature that is the primarily native aspect of his work.

While widely viewed and respected as an elder, Jemison was born in 1945, there is no indication that he is slowing down. There's much work to do and miles before we sleep. And man, you should see him dance.