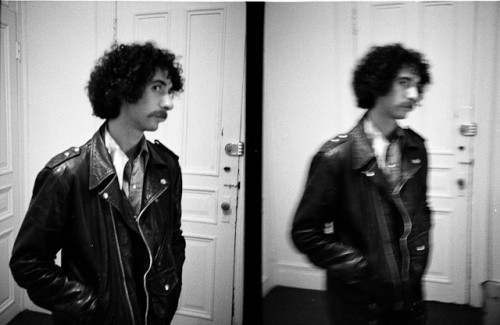

Berkshire Photographer Benno Friedman

Early Years: Woodstock, Rolling Stone, Playboy

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 25, 2014

At Brandeis University the Berkshire based photographer, Benno Friedman, was a couple of classes behind me. We knew each other better in the late 1960s. Through his hospitality, which extended to a family of friends, I became a frequent visitor to the Berkshires. He became a matrix for a community seeking alternative lifestyles and careers in the arts.

We met recently for lunch and an extensive interview.

This first part covers taking up fine arts and commercial photography. Other than basic darkroom tips from friends he is self taught. During the Golden Age of the 1960s this led to shooting for Rolling Stone, Playboy Magazine and other clients.

Charles Giuliano How did you get into photography?

Benno Friedman A girlfriend at the time invited me to join her in Europe. It was a great idea but in the short term I didn’t want to give up a commitment to the beginnings of a life in the arts.

At the time I was doing arc welding and large scale paintings.

I was in a bit of a quandary until someone suggested going to the Duty Free shop in the airport and buying a camera. In those days I flew as inexpensively as possible and ended up in the Amsterdam airport on the way to London. It must have been an airfare sale at the time. Back then Amsterdam was one of the largest shopping airports. They were the first to realize that people spend more time than they want to in airports and therefore provided them with shopping opportunities.

Since I was moving on to another country it was also duty free.

CG Is there a date?

BF The summer of 1966 just after I graduated (from Brandeis).

CG Did you buy a Nikon?

BF I probably bought a Nikkormat. I didn’t know much about what I was buying but it turned out to be a real workhorse. It was built like a tank. All metal and really heavy metal. Without bells and whistles it was a simple and functional 35 MM single lens reflex camera.

I started taking pictures. For a variety of reasons recently I contacted a well known environmental attorney. You may know him. We were in the same class at Brandeis. His name is Michael Rattner. He was an English major. We were talking about mutual friends and he mentioned that I was already taking pictures at Brandeis. So I had taken picture before, including pictures for my high school yearbook, but I never had any instruction. I shot all these pictures in Morocco which is where we ended up after London. We spent three weeks in Morocco. I shot all these pictures but didn’t know how to develop them.

Did you know Brynn Zucker who was a friend of Alice’s (Brock)? She was an early lover of Ray's (Brock). She also knew Richard Davis and his girl friend. After Morocco I spent the summer in the Lower East Side. Richard Davis was a photographer with a loft next to Fillmore East. He had a darkroom and taught me how to make a print.

CG How many rolls did you shoot in Morocco?

BF Maybe 15 to 20.

CG Black and white?

BF I only shot black and white for years. All of my early work, commercial and not, was black and white. It stayed black and white for my non commercial work much longer than my commercial work. There was a push from people giving me assignments to shoot in color. At that time I was shooting two and a quarter color because I was working in the record business shooting LP covers. So the format fit the dimensions of a record cover. I shot with a Hasselblad. For almost the rest of my career that’s all I used.

CG Would I know some of the albums?

BF Do we have to do that?

CG I’m curious.

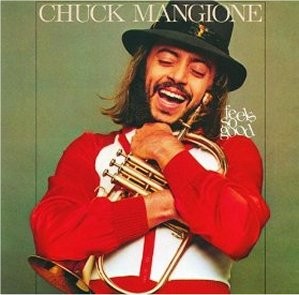

BF I never photographed the A list. Other than Billy Joel. In Jazz I did Dexter Gordon, David Sanborn, folk/ rocker Phoebe Snow, some people barely classify Chuck Mangione as jazz. I did seven covers for him.

CG Describe the process from acquiring a camera while on vacation to becoming a commercial photographer.

BF It was a golden age for lots of things. If you had a particular interest you could find an entree point. That’s the opposite of the situation today. Think of everyone you knew who graduated from college and had an interest and suddenly had a job doing it. That was true if you wanted to work in the art world, publishing. Think of your own story.

CG With no prior training or experience I established a career in criticism and journalism.

BF Today if you’re an internet wiz and come up with a new program and software you can still enter into what is still an open ended environment. The internet.

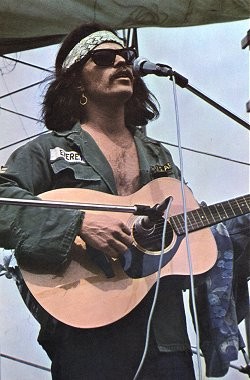

CG You shot Woodstock. As I understand it you handed the film over to a publication and never got it back.

BF I have some of it. Which maybe at the time I held back. I was photographing for Playboy and Seventeen. (laughing) Playboy wanted the musicians and Seventeen wanted the kids. Essentially I had to cover two completely different venues and assignments. That caused me to work extremely hard and fall asleep missing probably the best acts which came on after 2 AM.

On the last day I woke up and heard Jimi’s set in the background. I raced over and photographed the fields emptying of people. We had been living in the mud for three days. It was a wonderfully bleak haunting scene with Jimi Hendrix playing the “Star Spangled Banner.” With people straggling out. It’s amazing that they didn’t stay to hear this electrifying performance. By then everyone had had enough.

CG Do you have any of that film?

BF Only one or two shots of Jimi way in the background.

CG What happened? Did you give all the film to Playboy and they didn’t give it back?

BF Yeah Playboy and Seventeen. Not just them but Michael Wadleigh (also known as Michael Wadley, born September 24, 1939, Akron) who was one of the producers of the movie and booklet. There are a lot of my shots in the booklet. Things were a lot looser. I was a lot looser then and basically just trusted everybody to do the right thing and in many cases they didn’t.

CG You also shot interviews for Playboy. Wasn’t it their policy that you handed the film over to them?

BF Absolutely.

CG So you had no rights to the material. Is that correct?

BF Absolutely correct. I photographed some interesting people: Sting, Pete Townsend, a bunch of pretty interesting folks. It would have been nice to have the negatives. But Playboy had a policy of handing over and owning all of the film that you took for them.

CG Did they pay well?

BF No. They didn’t pay badly. At that time it was about $300 for an hour or two of work. That’s thirty or forty years ago so three hundred bucks then was decent.

CG You also shot for Rolling Stone.

BF In the early days.

CG There was the Isley Brothers incident when you shot them for Rolling Stone.

BF You already know it.

CG But not on record.

BF You’re dredging up one only two or three assignments that didn’t work out.

Rolling Stone called and asked me to go to Atlanta. It was the Fourth of July weekend and the Isley Brothers had a major performance. Traveling that weekend was always less than desirable. On any holiday weekend travel is a pain in the neck. In my business you just buckle up when the phone rings. Eat when you have the time and just go forward.

My assistant and I got ourselves together and went to Atlanta. For convenience we were staying at the same hotel. We made it in time to catch the last of the sound check. I covered it in real snapshot fashion with a Nikkormat and no lights. I just wanted to take some pictures and it was not the kind of work I normally do which is all set up and carefully lit. Very orchestrated.

I got off maybe five or ten shots but nothing really interesting. I asked the Isleys if I could come to their room and take a few more pictures. They weren’t happy about it but said sure. I went up and got about four shots up when, I don’t remember which one, said to me “Well, where’s the article?” I said “I don’t have the article.” They said “Well. We don’t do anything without approval.”

I said “I’m sorry but I can’t give you something that I don’t have and don’t have the authority to give you. I promise you that you will have it.” We called Rolling Stone and they said under no circumstances do they let musicians see or edit articles prior to publication. The Isleys absolutely refused to let me take any photographs. So I got on a plane and went home.

If it wasn’t for those few shots I took in their room lounging around in their underwear or whatever it was there wouldn’t be a shoot at all. They did have something to run.

CG They ran your photo!

BF Yeah. It was almost a slap back at the Isleys to say that you didn’t let us take a photo that you might have liked better and here is what our photographer was able to capture. It’s an off moment, unguarded, picture and this is how you’re going to be represented.

The same kind of thing in reverse happened with Leon Redbone.

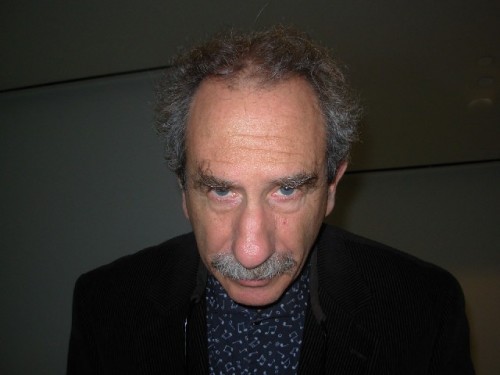

CG Who you resemble.

BF (laughing) I’m a chameleon and resemble lots of people. Annie Oakley.

CG Woody Allen.

BF Ringo Starr. There’s pieces of me that resemble lots of people.

Leon Redbone was performing nearby at the old Music Inn (Berkshires). The shoot was for an album cover as well. Maybe for the back of an album. I met with him before the concert and he said that he didn’t do photo shoots. He wouldn’t sit for one. It wasn’t interesting.

I explained to him that there was going to be a record and a cover and that he should give me an opportunity to work with him under controlled conditions that he would appreciate. Otherwise they would use something that someone shot from the audience. It would be a much less interesting picture. It could be unpleasant or showing him in a light that he didn’t care about. With that kind of logic he deferred and we had a wonderful photo shoot. Everyone was happy with the outcome.

CG You commented that Rolling Stone didn’t let the people they wrote about see the story prior to publication. Later the opposite was true. They couldn’t get access to A list artists without allowing them to see and edit the coverage. That started with Dylan and artists on that level. Rolling Stone and the media in general went from journalism to pr for celebrities.

I have turned down interviews because of those conditions. On rare occasions I have collaborated with subjects on articles. That only evolves from close and sustained relationships. Some peers are known for doing puff pieces previewing performances followed by negative and even hostile reviews. It’s a cat and mouse game with blame on both sides. That’s the norm now.

This summer one of the theatre companies organized press conferences. There was a half hour dialogue between the producer and as many as six actors or directors. They took questions for ten minutes and then we got two minutes of face time with from one to three individuals. Just what can you cover in two minutes other than hello and goodbye?

It was set up to get pr for the shows and not to allow for responsible and insightful journalism. I told the producer that it was a waste of time particularly as they denied photo access. Why bother. It was useless. Previously I had a number of interviews with that company for a half hour and more. It’s all about control.

That started for me some years ago when I interviewed the Cars who were in the studio doing Shake it Up in 1981. I had known the drummer Dave Robinson from The Modern Lovers when Arthur Gallagher and I booked them for college week in Bermuda.

The editor of the publication showed me the copy as censored by Ric Ocasek. I kept it and have thought one day of posting it as is. Or blowing it up for an exhibition. There have been similar incidents over the years where a source had gotten to an editor.

Not to say that we shouldn’t be edited. It’s always best to have another pair of eyes. Which I try to be for our contributors.

BF That was always a struggle between agents, publicists and publications. The leverage of doing a story on that celebrity and the drawing power for readers that impacted advertisers was always sufficient. The stars realized that they had the ace up their sleeves. I found and I am sure that you had similar experiences that if you can get to the performers they are reasonable people. It’s always the hierarchy of paid lackeys around them that denies access. Their business is to protect, shield and defend the artist. Often they make decisions that the artist wouldn’t want made. This doesn’t pertain to looking at copy (or approving images) which the artists would want to control.

Surely decisions of whether or not to grant an interview or photo shoot, or how long to give, where to do it and what the structure is, all that stuff became subject to negotiation. The handlers always have to prove to their clients how effective they are by how big a shield they provide. The client felt exposed without that shield.

CG In my early years covering rock was a blast. There was ready access to the Green Room and back stage. Most groups were friendly and accessible. Most of what I know about jazz came from talking with musicians in bars, restaurants, between sets or in hotel rooms. Captain Beefheart ordered a huge lobster and Herbie Hancock consumed three dozen raw oysters. Miles Davis combed his hair and looked at me in the mirror over his shoulder. I got plastered on schnapps in Copenhagen with Dexter Gordon. Elton John answered a knock on his door dripping wet wrapped in a towel. Over dinner Roland Kirk ranted about the motherfucking white jazz critics. Gerry Mulligan threw a tantrum in an elevator. Joe Cocker barged in on Tim Crouse and me smoking a reefer at the Tea Party.

Looking back on la vida loca we have few regrets.

From Wet to Dry with Benno reposted from Maverick Arts 2005.