Nikolai Astrup: Visions of Norway

At the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute through Sept. 19

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 28, 2021

The work of the artist Nikolai Astrup (1880-1928) was as narrow and deep as the fjords of his native Norway. While beloved in his native land he is unknown to all but a few art historians and specialists of 20th century Scandinavian art.

"Nikolai Astrup: Visions of Norway," is on view at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute through Sept. 19. This is the first exhibition of his work in North America.

"Astrup was multi-talented. He was a painter, a printmaker, a farmer, a horticulturalist and a conservationist. He also lived through independence from Sweden and the establishment of a new nation, Norway, which took place in 1905. He, therefore, shared with [Henrik] Ibsen and [Edvard] Greig the desire to forge a new national cultural language — music, literature, visual arts and architecture. This new language did not include Norwegian peasants in their costumes gazing at mountains and fjords but, rather, determined a new visual language that capture the essence of Norwegianess ...," stated MaryAnne Stevens, guest curator, former director of academic affairs at the Royal Academy in London. There was an online media tour of the exhibition.

It is likely that Astrup would resent being cast as a flag waver which is suggested in the title of a richly colorful exhibition of landscapes. It was a time when Norway was newly separated from Sweden. There was a cultural effort to forge a national identity. In Germany it took the form of the Volkish movement of which Emil Nolde is a primary example.

The Nazis embraced the Volkish movement for the same reason that it deified Richard Wagner. While Hitler vilified the Expressionists, who were purged from museums, an exception was made for Nolde who was left alone as a party member.

From what I gleaned researching this article, for the most part, Astrup was a loner and made sharp critical comments about the confectionary color of the French Impressionists and had little good to say about Norway’s most renowned artist, Edvard Munch (1863-1944). Ironically, Munch admired Astrup and owned his work.

The sense is that Astrup was a contrarian rebelling from fundamentalist upbringing as one of eleven children of a Lutheran minister. (Some accounts state a family of 14.) With his wife Engel Sunde they raised a family of eight in rural Norway. Essentially, on the other side of Lake Jølstravatn across from the village of Ålhus, his birthplace.

A sickly child, he took to making art as a refuge. His father mandated that he follow the family business. Fortunately, his mother scraped together enough money to send him to art school in what later was known as Oslo. There he thrived and earned a grant to study in Paris. There was also time in Berlin. He came to admire the early “volkish” peasant depictions of Vasilly Kandinsky then in Munich as well as Lovis Corinth with whom he studied briefly.

In his 20s he returned to Norway but kept up with trends through art journals.

It’s a struggle to connect Astrup to modernism. While a well trained and accomplished painter, overall, the work is conservative compared to that of Munch or the more radical expressionism of Nolde.

For the most part he colored within the lines. But as visitors to the exhibition have found, marvelously so. This is in every sense a sumptuous and galvanic viewing experience for both the general public and aficionados.

Some artists I spoke with have made multiple, even weekly visits to the exhibition. During lunch with Stephen Hannock I brought up his generous use of pthalo green. It is almost a verboten color to be approached with caution. For Hannock, a landscape painter, his saturated greens are remarkable.

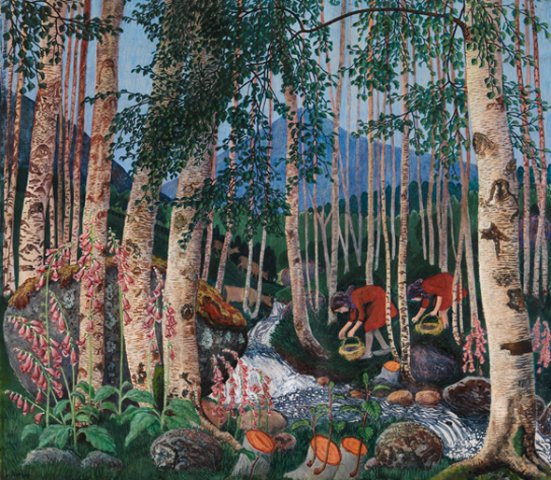

For my part I comment on how the paint is applied so lushly that the texture of birch trees stands out in tactile relief.

On the distaff side, I want more in the work of the best artists. The paintings, while lush and intense, also feel, as we stated in the beginning, narrow, and provincial. There is a domesticity that is hard to get by. Particularly for one having been nurtured on modernism and the extremes of the shock of the new.

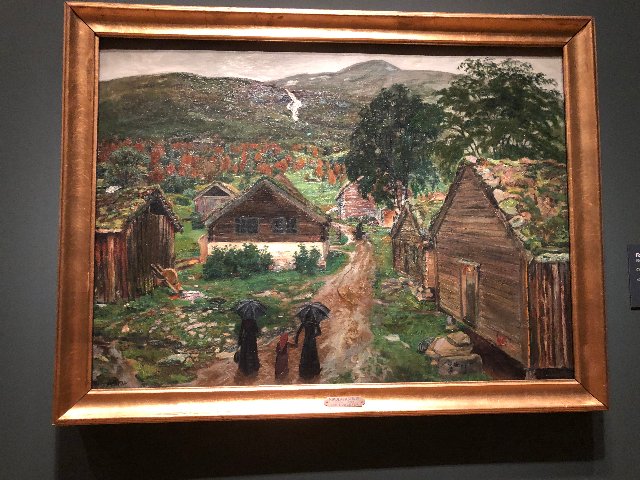

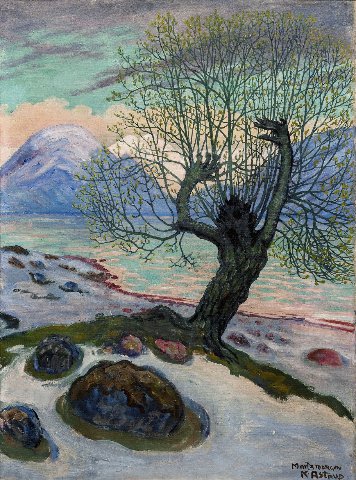

Essentially, Astrup was a landscape painter but one who avoided the spectacular. One might imagine what American artists like Church and Bierstadt would make of the fjords, mountains and winter scenes.

Only occasionally do we find figures in the work and less as narrative and more as staffage. There are portraits of him but not by him. We really don’t get to know his family other than as figuration in depictions of gardens and forests.

He painted things he knew that meant a lot to him. There is a plainness as the emotional intent gets lost in translation.

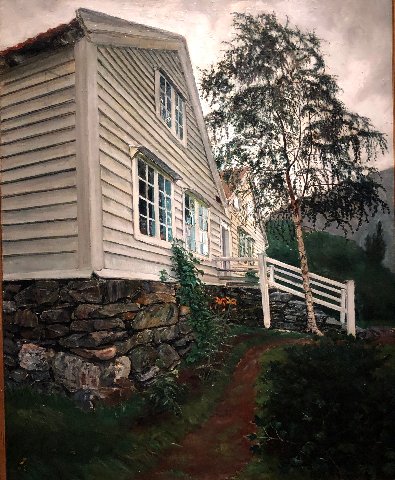

Entering the first gallery, for example, we encounter several paintings of the numbingly ordinary parsonage. One depiction is a side view from below grade looking up in perspective. Absorbing wall text and research we come to see the parsonage as a looming, haunting, iconic memory. It can not have inspired happy anecdotes and has a resultant, grim, Nordic austerity. The artists of Norway are generically masters of gloom. It reflects theories of the gothic, dyonisian Northern European sensibility compared to the apollonian South. That has to do with light or its absence.

But in a contrarian bent the paintings of Astrup focus on the brief but verdant summers. He makes scenes of Jølster between the Sognefjord and the Nordfjord inviting but I doubt that this exhibition will boost tourism.

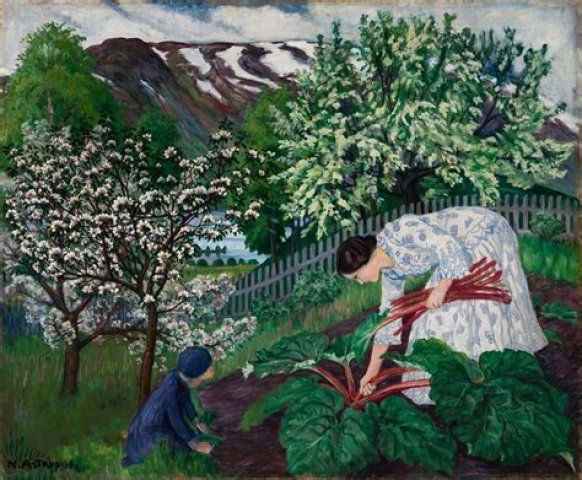

There were sales during his lifetime but a constant struggle to sustain a growing family. Part of that strategy was the creation of terraced gardens. A typical painting is Rhubarb at Sandalstrand. His wife is seen in profile bent over harvesting in early spring. Nearby fruit trees are in bloom.

We learned that he made wine from rhubarb as well as home brewing beer. One senses that they lived well from the gardens and livestock.

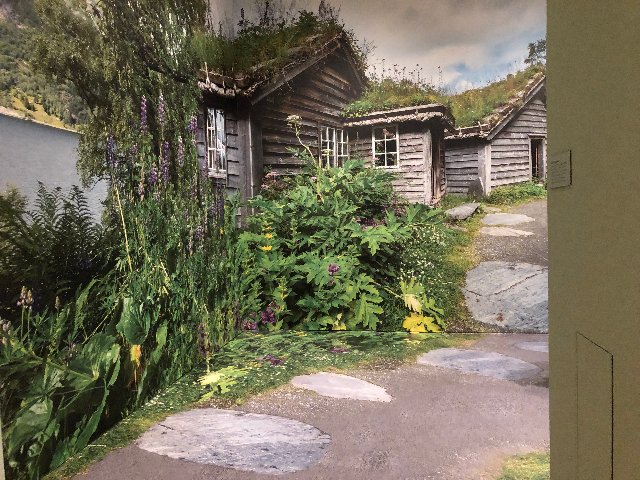

There are a number of views of his home Sandalstrand. It is a warren of small houses that he relocated. The views are quaint and enticing with sod growing on roofs as part of natural insulation.

With a brief growing season there is a focus on vegetation that thrives in that circumstance. There are major works devoted to plucking foxlove in the forest.

As we twist and turn through the galleries of the Clark installation there are panoramic photo murals of what we encounter in the 85 works on view. I much enjoyed these transitions that blew up what one views intimately in the paintings and prints.

That asymmetrical ambulation led to a small gallery of prints and carved woodblocks. One critic described this instillation of multiple states of prints as too academic and a speedbump (my term) navigating the flow of painting.

I beg to differ. Astrup was arguably most notable and innovative as a printmaker. He was inspired by Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints. This entails in Astrup’s practice some eight or so blocks each for a different color or aspect of the design.

Uniquely, he used oil paint rather than printer’s ink. That meant long drying times between applying layers of color. We see the states of this labor intensive process as well as examples where he hand painted on the resultant image.

The next gallery explored the relationship between the prints and paintings. It rightly situates the artist’s intent for multi media. Primarily for painters the use of printmaking provides cheaper multiples of their work. Given the artist’s limited market, this was likely not the motivation. Arguably, it took more time and labor than to produce paintings.

Several wood blocks in vitrines proved to be among the most stunning and fascinating works in the exhibition.

Our tour ended with a knockout gallery of large depictions of solstice bonfires. They were regarded as pagan rituals by his father. With defiance he embraced depicting these festive village celebrations of music, dance and libations. It reminded me of one of my favorite Ingmar Bergman films “Smiles of a Summer Night” (1955). A detail of a man perched on the top of soon to be lit blaze could be a still from the movie.

At the age of 47 the artist died of pneumonia. In a late work there is a hint of what might have been. It’s an unfinished interior scene depicting a festive groaning board celebrating Christmas. There is the ghostly nude presence of a child. The dense array of still life objects remind me of Matisse who the artist knew of and admired.

In departing from the familiar pattern of mounting blockbusters the Clark took a chance in featuring an obscure artist. By word of mouth the show has done well. It will be gone soon. Yes there are questions and issues but this work will linger with me forever.