Merging Influences at Monsterrat College of Art

A Challenging and Timely Look at East/West Tensions

By: Shawn Hill - Sep 01, 2007

August 27—October 27, 2007

Montserrat College of Art Gallery

23 Essex St.

Beverly, MA

http://www.montserrat.edu/galleries

Curator Shana Dumont has identified a compelling national impulse and interest in this lush and timely show of new paintings and other media. Though all Americans, the artists in this show (which has an opening reception on September 13) have cultural origins in Egypt, Iran, India, China and South Korea. Their challenge, in this age of increasing globalization (which Dumont defines succinctly in the show catalog as "the increasing connection, integration, and interdependence of people over national and geographic boundaries"), is to speak to their current lives as Western citizens without forgetting the powerful cultural traditions of the East.

Dumont has chosen mostly paintings and works on paper, and an immediate parallel in artistic style is evident. The large-scale pieces in this show have a resonance with the very American idiom of Abstract Expressionism (a style Montserrat College has a long history of supporting as well). Whereas the artists of that original era such as Jackson Pollock and Franz Kline looked to the East (and such concepts as Zen, calligraphy and the floating world) to re-invigorate the European tradition of modernist abstraction (and to break from traditional notions of Renaissance perspective), these artists come out those Eastern traditions (such as the unfolding vistas of Chinese watercolors, or the floral decorations of illuminated manuscripts and woven rugs) naturally. Several find new affinities with gestural painting.

C. Meng's large scale monochrome works seem almost devoid of incident, as portraits, calligraphy and floral patterns are scattered across vast expanses of cream and dun-colored canvas. But careful attention reveals the sources of some of these figural fragments in Neo-Classical, Baroque and Romantic Western painting. Portraits of Asian women are rendered in the style of 18th century Dutch masters, and other interesting juxtapositions are like little Easter eggs opening up surprising moments of connection, like flowers on branches that span Meng's vast surfaces. He forms connections between cultures that were once physically worlds apart.

Ahmed Abdalla's paintings and pen and ink drawings have a busy, frenetic and seething energy. The marks are rough, fast, profuse. But in the drawings especially, they coalesce into calm and timeless larger forms. "Witness: A Story Without an Orator #5" has various spheres in gray and white hovering over a deep black shimmering pool. Fronds like Spanish moss or maybe distant rain clouds seem to flow down towards this pool from the hovering globes, and we can't tell whether we're looking through a microscope or a telescope into deep space.

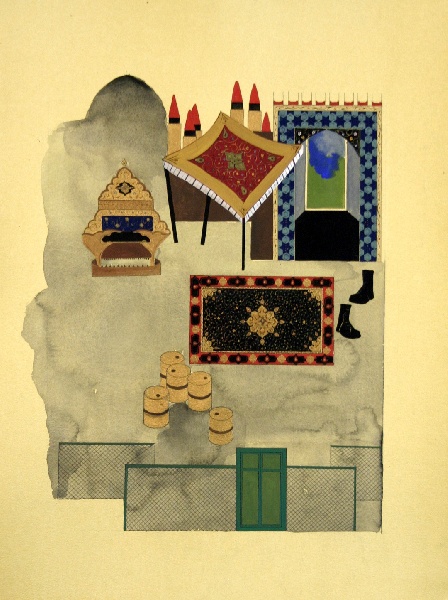

Shiva Ahmadi's delicate gouache paintings refer to ancient patterns in Persian books and carpets; architectural forms like windows, kiblah walls and pointed arches organize the space. But she updates tradition with timely inclusions: ammunition shells, barrels of oil, military boots and other martial references compete with golden thrones and walls adorned with flowers. There's a subtle wit at play here.

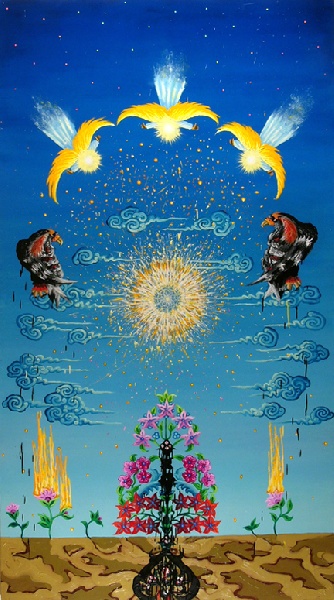

Kamrooz Aram's symmetrical "Celebration/Desert Station (III)" is one of the least loose and gestural works in the show. Aram's incorporation of Western style comes not in the bright colors or the hard-edged shapes to his symbolic motifs (angels, falcons, burning bushes) but in the distinct arrangement of each element in a new synthesis that recalls the lurid quality of Pop art and computer games. There's a sense here of symbols stripped from their original context, but re-organized into a new user-friendly menu of options. The question is raised: does such cultural blending lead to confusion, or new iterations that transform the past without obscuring the old meanings?