Porgy Gets His Bess at ART

Gershwin's Opera Is Moving Musical Theater

By: David Bonetti - Sep 03, 2011

Geez, what was all the fuss about?

If you paid any attention to certain self-appointed custodians of theatrical correctness, led most articulately by Stephen Sondheim, the reigning Grand Pooh-Bah of the Broadway musical, who wrote a blistering letter to the New York Times, you’d have feared that Attila the Hun, in the guise of ART director Diane Paulus, aided and abetted by a pair of feminist and racial avengers, namely playwright Suzan-Lori Parks and composer Diedre L. Murray, were conspiring to trash George Gershwin’s operatic masterpiece “Porgy and Bess.”

Well, it didn’t happen. The show they put on is vibrant, moving, exhilarating in parts, musical and largely respectful of the source material. In an interview in the Boston Phoenix, Murray characterized the work as a “valentine to the black community” of which she felt herself to be the “custodian.” Too bad the prophets of doom didn’t focus on those words rather than other ill-advised statements Paulus, Parks and soprano Audra McDonald made to the New York Times and the Boston Globe.

So hats off to Paulus and her team and especially the dynamic cast, lead by a sensational McDonald, for making opera safe for Broadway.

But I am writing here as a custodian as well - as a watchman for opera, specifically “Porgy and Bess” as opera. I saw “Porgy” staged only once before, in 1995 at the San Francisco Opera in the much-toured 1976 Houston Grand Opera production. (I’d also seen the much-maligned Otto Preminger movie when it came out and I loved it – but I was only 12, so what did I know.) I went with a highly opinionated friend, and we both expected to experience more of a revue like Gershwin’s other excursions into musical theater than a real opera. After about 20 minutes, however, we looked at each other in astonishment – this was a real opera, through-composed (meaning the dialogue between arias and ensembles was sung) and performed by operatically trained singers whose rich voices were unamplified. (The Bess was Boston Conservatory grad Roberta Laws, whom I had heard a decade before bring the house down in the title character in “Iris,” a neglected work by Italian verismo composer Pietro Mascagni, at Jordan Hall.)

Despite some longueurs and confusing crowd scenes, the Houston production in San Francisco’s imposing opera house was a thrilling evening. “Porgy and Bess,” it turned out, was more in the tradition of Mascagni’s masterpiece, “Cavalleria Rusticana” (“Rustic Chivalry”), a sordid tale of love and murder in a provincial Sicilian town, than with Gershwin’s own “show,” “Lady, Be Good.” It is, in my opinion and that of those better capable of making such a judgment, the greatest American opera, barely matched in the 76 years since its Boston debut, “Nixon in China” by Worcester County-born Bay Area composer John Adams, the only legitimate competition. But it is true that Gershwin had his feet in both Tin Pan Alley and the concert hall and opera house, which has complicated matters about his intentions and achievements.

So I too, like Sondheim, was nervous about what Paulus et al. were about to unleash - especially after the previews in the Times and the Globe - which would undoubtedly turn out to be the “Porgy” this generation experiences just like the Houston production was for more than 20 years.

In case you have any doubts, this will be a big hit. For good reasons.

There is no question that changes have been made to the original text. But what’s new about that? Gershwin and his collaborators - his brother, lyricist Ira Gershwin; DuBose Heyward, upon whose book the opera was based; and his wife Dorothy, who helped create the play that had had a Broadway success - made feverish changes after its opening night at the Colonial Theater on Boylston Street, cutting some 45 minutes from the original before it moved on to Broadway, where it failed to thrive. Broadway, then as now, preferred the meretricious to work of real quality. In the years since, it has been presented both as a musical and as an opera.

Such changes are not unusual. It is nearly impossible to encounter anything on the stage, opera, musical or straight-theater, that appears in its original form. Even the Boston Early Music Festival, which takes pride in presenting almost archeologically correct productions of forgotten baroque masterpieces, cut copious amounts from its recent presentation, Steffani’s “Niobe, Regina di Tebe.” (And as far as I’m concerned, they could have made more.) In the 18th and 19th century, composers willingly recomposed works as they moved from theater to theater with their different resident casts and requirements, Mozart, Rossini and Verdi among them.

Tinkering with a text to make it work on the stage of the moment is so commonplace as to be beyond comment.

Unless, of course, the tinkerer screws up.

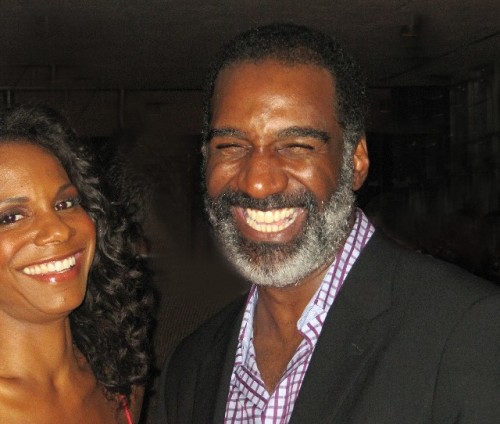

In a larger sense, the ART tinkerers did not screw up, although there were some things about the adaptation that I did not like: The amplification, for instance. The moment the orchestra started to play the familiar overture, I was aware of it. It sounded like a recording. Why have a live orchestra – 17 pit players – if it sounds canned? The soundscape for the singers was more subtle: One could believe that what one heard came directly from the singers’ lips even if it was filtered through a system that made everyone, both operatically trained singers like McDonald and her Porgy, Broadway stalwart Norm Lewis, sound compatible. The sound design, by Acme Sound Partners, had one instance of genius. In the evocative scene when the Strawberry Woman, Honey Man and Crab Man pass through Catfish Row hawking their wares, the sound is totally divorced from the singers, a free-floating aural experience that underscores the dreamlike quality of the scene.

But opera is based on the idea that voices untouched by technology fill a theater with real, natural, live sound. Few cast members were operatically trained: McDonald; Phillip Boykin, who played her personal devil Crown; and a few characters in the large ensemble cast. They were at a disadvantage: they had to scale down their voices so as to not blow other cast members off the stage. Still, it largely worked. There was no question that McDonald is a diva at the peak of her career. (And isn’t it a tragedy that she has chosen to sing on Broadway rather than at the Met, Covent Garden and La Scala?)

Even though Paulus hopes to make her “Porgy” as Broadway-safe as her production of “Hair” in order to make money for the American Repertory Theater and ensure her tenure there, there are elements of the operatic nature of the work that she could not negate. Yes, much of the sung recitative is now spoken, and cuts beyond Gershwin’s own were significant – I have little objection to most of them – but the nature of the beast remains inviolable. The duet “Bess, You Is My Woman Now,” remains a great OPERATIC duet on the model of Puccini’s “Che Gelida Manina” from “La Boheme,” an operatic touchstone with which Gershwin was undoubtedly familiar. Even a Broadway popularizer can’t vitiate it, and, despite their different vocal training, McDonald and Lewis nailed it, making it a riveting theatrical experience, the highlight of the entire evening. And folks – that’s OPERA, whether you like it or not. And how could you not? The fear of opera Paulus and her team evince is unfounded. When they cite its lack of intimate moments, one wonders if they've ever heard the Countess in "The Marriage of Figaro," Desdemona in "Otello" or the Marschallin in "Der Rosenkavalier," among many others, express their fears, desires and disappointments.

There are problems that have nothing to do with whether the production is an opera or a musical. The set, for instance. Instead of evoking the “folkloric” Catfish Row of the original, designer Riccardo Hernandez took the abstract route. Nothing wrong with that, but what was he thinking? The curving wooden wall that encloses the action, making it claustrophobic, suggests a cave or mountain refuge more appropriate for Carmen and her gypsies than the fisher community of Charleston, South Carolina. When the unit set lifts a corner to reveal a raging hurricane, it's almost ridiculous. There will be work done on the production before it hits the Great White Way. One hopes a new set design will be a high priority. Costumes by Esosa, lighting design by Christopher Akerlind and especially the choreography by Ronald K. Brown, which evoked African dance without stereotype, saved the scenographic day.

One also hopes that the opera’s original conclusion remains intact. Among the most misguided changes Paulus and Parks intended to make was to create a “happy” ending in which Bess, who had, according to the text, run off to New York with the dope dealer Sporting Life, instead stayed in Catfish Row with Porgy. Reason prevailed and, according to believable reports (the New York Times), the original ending was restored the night of the press preview. A proud Porgy, standing tall, in control of his life and destiny, leaves Catfish Row to follow the woman he loves to New York. Not only does that make dramatic sense, it reflects the reality of the time. In the 1920s, when the opera is set, African-Americans by the thousands abandoned the land of apartheid and moved North to Chicago, Philadelphia and New York to be free. (One of the great leitmotifs of the opera is the reprise of two themes – “going to the promise land” and “there’s a boat leaving soon for New York,” which over time become conflated into one yearning to escape the oppressive South.) If that isn’t a happy enough ending for the brain-dead Broadway audience that flocks to “Wicked” and “Billy Elliott,” so be it.

Okay, we go to both opera and musical theater to hear the singing and the dramatic expression, which are at best one and the same. Although it worked as an ensemble, the cast was of mixed quality. For McDonald, Bess is the role of a lifetime. She portrayed the cast-off woman as the drug-addled, dependent character she is, hunched over, twitching, casting her eyes suspiciously at anything that comes her way. With a perhaps too-prominent scar across her cheek, she made Bess’s vulnerability all too clear. She sang with soaring highs and desperate lows, even as she roped in her natural vocal force for the sake of the cast. She inhabits a much realer world than the glamorous Dorothy Dandridge did in the 1959 film. You couldn’t help but fall in love with her Bess. Norm Lewis, a handsome and well-built man, made the crippled Porgy a believable character despite his own physical attributes. His leg is withered, but his spirit and his body are not. It is totally believable when he kills Crown. And his singing was more than serviceable. If “Porgy and Bess” were a musical, which it is not, he would be the ideal Porgy. Philip Boykin, the other operatically trained principal, was menacing as Crown in a way that his baritone only underscored. Comic David Alan Grier made Sporting Life a believable trickster, the man from outside who wreaks havoc in a stable community. His singing and dancing were merely adequate, but his “It Ain’t Necessarily So” brought down the house. Also terrific was NaTasha Yvete Williams as Mariah, the motherly woman who holds the community together.

However, Nikki Renee Daniels, whose Clara sings the iconic “Summertime” at the very start of the work, and Bryohna Marie Parham, who as Serena sings “My Man’s Gone Now,” didn't have the chops for their big numbers. Daniels’s soprano was weak and strained to meet the high demands of the role. Parham failed to put across one of the most moving moments of the opera, her vocalise at the end of the aria weak and truncated. If you need to find better renditions of “Summertime,” you don’t have to go far – McDonald’s reprise of the melody later on in the opera makes you hear it as if for the first time. Not to mention famous versions by Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Leontyne Price, Kiri te Kanawa and Janis Joplin, among others readily available on disc or online. And if you want to hear a harrowing version of “My Man’s Gone Now,” go to YouTube for McDonald’s concert version with Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony at Carnegie Hall. OMG!!!!

So what more is there to say? Diane Paulus’s “Porgy and Bess” is a brilliant reinterpretation of a classic American opera for contemporary audiences who fear the word “opera.” It has made acceptable tweaks with the original. And if it makes a few more before it opens in New York it will be a more durable artifact for our benighted times. When you see it, remember that those in power want to return us, black, white, Hispanic and Asian, to the oppressive economic and social situation that prevailed in South Carolina in the 1920s. For apartheid-era African Americans of Charleston, New York City was the promised land. Where can we go today?