Ibsen's John Gabriel Borkman

Stratford Festival of Canada

By: Herbert M. Simpson - Sep 03, 2016

John Gabriel Borkman

By Henrik Ibsen

Translated by Paul Walsh

Stratford Festival of Canada

August 2 to September 23, 2016

Tom PattersonTheatre

111 Lakeside Drive, Stratford, Ontario

Directed by Carey Perloff

Cast: Sarah Afful, Natalie Francis, Deidre Gillard-Rowlings, Seana McKenna, Lucy Peacock, Scott Wentworth, Antoine Yared, Joseph Ziegler Set Designer and Costume Designer: Christina Poddubiak; Lighting Designer: Bonnie Beecher; Sound Designer: Josh Schmidt;

This was the world premiere of Paul Walsh’s translation from Ibsen’s Norwegian, which the Stratford Festival commissioned. I haven’t read or seen the play since Harry Truman was President, so I can say only that this version seems clear and effective with no jarring anachronisms that might obviously conflict with Ibsen’s original. In fact, the play deals with a former bank manager who illegally invested his customers’ deposits in a grandiose scheme.

Borkman couldn’t make up the shortcomings in his expenditures for a massive industrial development before the deficit led to bankrupting the entire town, losing its industry, and ruining many of its inhabitants. So this doesn’t seem to be exactly an outdated topic.

But the action seems even more dramatically subordinated to the argumentative dialogue than usual in Ibsen’s plays, and the plot development in the final act suggests another title: “Eight Characters In Search of a Conclusion”. We learn from Borkman’s wife, Gunhild, that eight years after being released from prison, he inhabits the floor upstairs, pacing the length of the floor constantly in the daytime, but virtually never intrudes on her residence on the first floor.

|

When her twin sister Ella, visits, after years of absence, we learn that the sisters do not speak to one another, that Ella owns the mansion but lives in town, and that after Borkman’s trial and incarceration, his and Gunhild’s son, Erhart, was raised by his aunt Ella and lived with her until he began studies in the city. Ella wants to change Erhart’s name to her married name and make him her son and heir.

We later hear that Ella has learned that she has a fatal illness. Next we see Borkman with his only visitor, Vilhelm Foldal, a clerk, also ruined financially by Borkman’s emberzzling but encouraged by Borkman to pursue his dream of composing an opera. He has a very young daughter who is an actually talented musician. Of course, Gunhild opposes giving her estranged son to Ella, but Borkman agrees to the idea. Then we learn that young John Borkman and Ella were lovers, but Borkman gave her up and married her twin sister to please the man who wanted Ella and got Borkman the bank manager position.

Finally we do meet the son, Erhat, who isn’t interested in being the pawn of his father, mother, or aunt, because he is already the pawn of a very self-reliant, sexy woman deserted by her husband.

In the last act, we quickly deal with these conflicts, The son and his very independent female seducer buy an enclosed big sled and leave the country, taking Foldal’s young daughter with them, I’m not sure why. Borkman has some sort of epiphany and wanders out into the snow, dying on a mountaintop. Ella goes with him, but wanders back to the mansion despite a broken leg. And Gunhild for some reason feels it right to say that the twin sisters can now reunite.

Christina Poddubiak’s designs, very much assisted and modified by Bonnie Beecher’s complex lighting, manage sufficient impressions on the Patterson Theatre’s long, straight thrust stage to seem suggestive enough for the first and second floor of the mansion, the snowy exterior, and the mountain top, without ever being literally realistic.

The changes in plot and revelations are almost entirely in speech, not action. And the final half-hour or more is all restatement to the point where I kept thinking repeatedly, “Write ‘Curtain. The End’. Write Curtain, The End.”

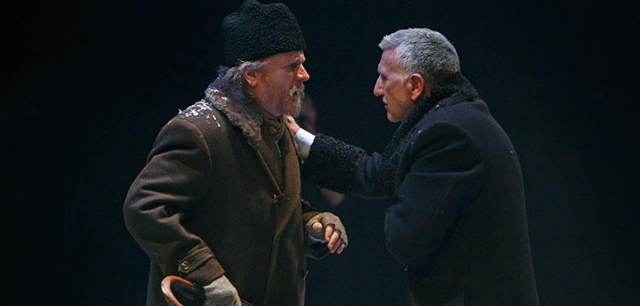

But this production is worth seeing less, I believe, for a seldom-seen, lesser Ibsen play, than for a sensitively directed, brilliant cast. Ibsen certainly invests the ruined, deluded Borkman with fanatic passion, but it is almost miraculous how lucidly Scott Wentworth embodies Borkman’s deteriorating physical condition and overpoweringly impressive deluded conviction. We laugh at his callous reactions to others but are almost convinced that the downfall of his giant ambition was tragic.

The plot development may be drawn out and repetitious, but its dramatic effect onstage is mesmerizing. Certainly the same should be said of Lucy Peacock’s Mrs.Gunhild Borkman, whose bitter passion practically jumps out from her rigid body clutching the arms of the chair she seldom rises from in the opening scene.

Seana McKenna’s Ella is a more varied, dynamic role, passionate in loving memories as well as antagonistic ones, but she too demands our constant attention, and ages and weakens at the end by will, not any change in outward appearance. Joseph Ziegler’s Vilhelm Foldal is so open and honest in his heartfelt responses that I believed and liked the man, despite the fact that he seems to be written as a fool. And in the small role of the sexy, freewheeling Mrs. Fanny Wilson, Sarah Afful makes a strong impression as a willful, no-nonsense powerhouse. I did want the play to end, but I appreciated the chance to applaud the performance.