Ross On Wagnerism

The Intoxification of Baudelaire

By: Susan Hall - Sep 03, 2020

Alex Ross, whose Wagnerism is to be published on September 15th, first heard Wagner on a LP record borrowed from his local library. Listening to Lohengrin, he was neither transformed nor transfixed. The Meister is not a free pass to paradise. Yet many listeners are instantly seduced by a steady procession of creeping chromaticisms. The composer Emanuel Chabrier took a few days off from his legal practice in Paris to hear a special “A” Wagner had written for the cello. He never returned to the law. Inspired by the “A,” he composed for the rest of his life.

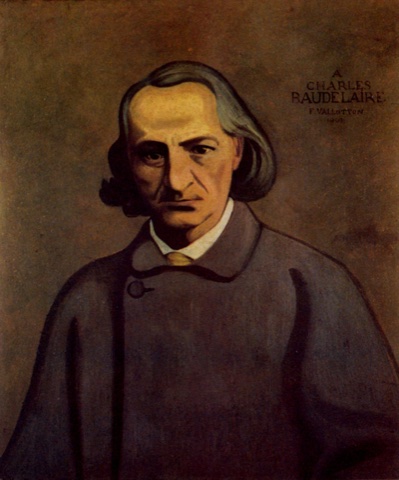

Charles Baudelaire, the French poet, heard Lohengrin and was changed forever. Baudelaire, a star of Ross’s sweeping picture of Wagner’s impact across the globe, “found himself” in Wagner’s music.

We meet the poet as he is first recognized in France. Baudelaire appears to have been born on the composer’s wave length. At home, he tells his mother that Fleurs de Mal has been created in savage anger and patience. Translate feeling and form.

Cross fertilization of art forms is tantalizing Baudelaire’s fellow creators. Ross quotes some lines from Fleurs de Mal written before Baudelaire discovered the Meister. “Vying to spend their last heat/Our two hearts will be two vast torches,/ Reflecting their double light/In the twin mirrors of ours souls.” They are redolent of Tristan, still waiting in the wings. Musical notes and words are being subjected to new ideas swirling across Europe.

In the early stages of the French national obsession with Wagner, Friedrich Nietzsche wrote: "Very modern, right? Parisian? Very decadent?” He also notes that Baudelaire is the first intelligent follower of Wagner.

Baudelaire had become fascinated by decadence when he read some poems of Edgar Allan Poe. In decadence, “unity breaks down, each page is an independent, and so on from sentence to word.” Ross compares this to Tristan, full of disconnected, groping phrases. In fact, Tristan would set the course for an avant-garde art of dream logic, mental intoxication, formless form and limitless desire.

Baudelaire had already writer about dandyism, an excess in dress and presentation. On hearing Wagner, he extended this notion to a broader one of "excess." Moderation has never been a quality of great art, even if it is minimalist.

Baudelaire wrote Wagner was a cry of gratitude: “…this cry…from a Frenchman, …born, moreover, in a country where people hardly understand painting and poetry any better than they do music. First of all, I want to tell you that I owe you the greatest musical pleasure I have ever experienced…you conquered me at once…At the outset it seemed to me that I knew this new music, and later, on thinking it over, I understood whence came this mirage; it seemed to me that this music was mine, and I recognized it in the way that any man recognizes the things he is destined to love. To anybody but an intelligent man, this statement would be immensely ridiculous, especially when it comes from one who, like me, does not know music.” Wagner sought out Baudelaire and wrote of him: “I would never have believed that a French writer could so easily understand so many things.”

All Frenchman were not as enthused. Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam, a poet and playwright, was said to have “a punch bowl flaming in his brain.” He writes, "I love Wagner, but the music I prefer is that of a cat hung by his tail outside a window and trying to stick to a pane of glass with its claws.”

Yet Baudelaire thought often about Wagner’s effect. “The thing that struck me the most was the character of grandeur…the solemnity of the grand passions of man. One feels immediately carried away and dominated. Quite often I experienced a sensation of a rather bizarre nature, which was the pride and the joy of understanding, of letting myself be penetrated and invaded — a really sensual delight that resembles that of rising in the air or tossing upon the sea. And the music at the same time would now and then resound with the pride of life. Generally these profound harmonies seemed to me like those stimulants that quicken the pulse of the imagination… There is everywhere something rapt and enthralling, something aspiring to mount higher, something excessive and superlative. the supreme utterance of a soul at its highest paroxysm.” From the day when I heard your music, I have said to myself endlessly, and especially at bad times, ‘If I only could hear a little Wagner tonight.’”

Baudelaire echoes Tolstoy as he speaks of emotional infectiousness as the most significant criterion for great art, the imaginative act of projecting oneself into a work of art, inhabiting it, possessing it while being possessed by it in much the same way that Baudelaire did Wagner’s music.

Like Anthony Burgess of A Clockwork Orange, Baudelaire finds a psychedelic moment… an instant of recognition of verbally inexpressible spiritual realities. In language like astronauts describing the cosmic view of the over effect, Baudelaire articulates the transcendent effect Wagner’s music had on him, his willing receptivity, which great art unleashes in its audience, swings open the doors of perception.

Ross notes: The bonding phrases between the units of the operas are clear, even when the connective tissue is not clear. This helps Wasgner capture the texture of unconscious, dreaming states. This Ross identifies as a literary idea known as parataxia. Wagner’s music has it. Baudelaire likened the music’s effect to that of opium.

Interesting that people who overindulge in alcohol and drugs quickly connect to the Meister’s music. What else can dissolving into this music be except 'me.' Baudelaire reminds us that most artistic appreciation happens in the shadows, in the sinews, in the silence of private experiences, the ineffable but transformative experience that the artist had afforded him.

Listen to Lohengrin—"alone, where no eavesdropper will hear the salutations of the heart,” as the Knight of the Holy Grail sings. Ross sings too in his monumental work, with all the pleasures of a Wagner opera and then some.

Published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux

Available at Bookshop.org

Part II of IV