Elgar at Bard, Weekend II

Of science and religion, Music Halls and World War I, Elgar's Symphonic work, and Gerontius

By: Michael Miller - Sep 06, 2007

18th Annual Bard Music Festival: Elgar and his World

Weekend Two August 17–19, 2007

From Romanticism to Modernism: World War I and the End of the Long 19th Century

[for Part I, click here.]

Friday, August 17

Symposium

Charles Darwin and Cardinal Newman:

Religion, Science, and Technology in the Elgarian Era

Multipurpose Room, Bertelsmann Campus Center

10:00 am – 12 noon

1:30 pm – 3:30 pm

Deirdre d'Albertis, moderator; and others

Elgar by Ken Russell

Weis Cinema, Bertelsmann Campus Center

4 pm

Program Six

Elgar and the Salon

Sosnoff Theater

7:30 pm Preconcert Talk: Sophie Fuller

8:00 pm Performance: Sasha Cooke, mezzo-soprano; William Ferguson, tenor; Jupiter String Quartet; Jeremy Denk, piano; Piers Lane, piano

Edward Elgar (1857–1934)

Concert Allegro, Op. 46

Dream Children, Op. 43 (arr. for piano)

Echo's Dance, from The Sanguine Fan, Op. 81 (arr. for piano)

May Song

Skizze

Gabriel Fauré (1845–1924), La bonne chanson, Op. 61

Frank Bridge (1879–1941), Piano Quintet in D Minor

Songs by Maude Valerie White (1855–1937); Ethel Smyth (1858–1944); Hubert Parry (1848–1918); and Roger Quilter (1877–1953)

Saturday, August 18

Program Seven

"God Bless the Music Halls": Victorian and Edwardian Popular Song in America and Britain

Olin Hall

10 am Performance with commentary by Derek Scott, with William Ferguson, tenor; Thomas Meglioranza, baritone; Gloria Parker, mezzo-soprano; Tonna Miller, soprano; and Spencer Myer, piano

Program Eight

The Great War and Modern Music

Olin Hall

1 pm Preconcert Talk: Byron Adams, replacing Alain Frogley

1:30 pm Performance: Bard Festival String Quartet; Claremont Trio; Laura Flax, clarinet; Weston Hurt, baritone; Ieva Jokubviciute, piano; Jennifer Koh, violin; Scott Williamson, tenor

Edward Elgar (1857–1934)

Violin Sonata in E Minor, Op. 82

Carillon, Op. 75

Claude Debussy (1862–1918), Berceuse heroique, for piano; Noel des enfants qui n'ont plus de maison, for voice and piano

John Ireland (1879–1962), Piano Trio No. 2

Arthur Bliss (1891–1975), Clarinet Quintet

Songs by George Butterworth (1885–1916) and Ivor Gurney (1890–1937)

Program Nine

Elgar: The Imperial Self-Portrait

Sosnoff Theater

7 pm Preconcert Talk: Christopher H. Gibbs

8 pm Performance: American Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Leon Botstein, music director

Edward Elgar (1857–1934)

Crown of India Suite, Op. 66

Falstaff, a symphonic study, Op. 68

Sospiri, Op. 70

Symphony No. 2 in E-flat Major, Op. 63

Sunday, August 19

Panel Three

Constructions of Masculinity from Dorian Gray to Father Brown

Olin Hall

10 am–noon

Byron Adams, moderator; Leon Botstein; Richard Dellamora; Sophie Fuller

Free and open to the public

Program Ten

Elgar and Modernism

Olin Hall

1 pm Preconcert Talk: Diana McVeagh

1:30 pm Performance: Carolyn Betty, soprano; Bard Festival String Quartet; Piers Lane, piano; Sophie Shao, cello; Bard Festival Chorale, James Bagwell, choral director; Jeremy Denk, piano

Edward Elgar (1857–1934)

String Quartet in E Minor, Op. 83

Frederick Delius (1862–1934), Sonata for cello and piano

Gustav Holst (1874–1934), Choral Hymns from the Rig Veda, Third Group

Cyril Scott (1879–1970), Two Pieces, Op. 47, for piano

Herbert Howells (1892–1983), Piano Quartet in A Minor, Op. 21

William Walton (1902–1983), Three Façade Songs

Program Eleven

The Culture of Religion: The Dream of Gerontius

Sosnoff Theater

4:30 pm Preconcert Talk: Charles McGuire

5:30 pm Performance: Carolyn Betty, soprano; Vinson Cole, tenor; John Hancock, baritone; Jane Irwin, mezzo-soprano; Bard Festival Chorale, James Bagwell, choral director; American Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Leon Botstein, music director

Edward Elgar (1857–1934)

Selections from The Kingdom, Op. 51

The Dream of Gerontius, Op. 38

The more I reflect on music the more I am struck by the manifold ways in which a musical works are linked with groups or communities. Once the listener puts together a few instruments, rhythms, and melodic threads, an idea of some human context begins to appear. While the musicologically inclined might be tempted to consider this from a historical point of view, it is not at all necessary. If the original context is unfamiliar to us, we automatically create one for ourselves, most likely some idealized reflection of our immediate surroundings, and we become absorbed in the music, "tuning out" as much of our immediate physical surroundings as possible. On the other hand, it might be pure fantasy, a daydream derived from some scrap of knowledge of the composer, or one's own unfulfilled desires. It might well be musically beneficial, functionaing as a bridge in one's listening, a bridge to full absorption in the music.

If we choose to look at it biographically, we can understand it in terms of a composer's struggle to find an audience (Elgar) or flair for creating one (Liszt). This is an especially interesting question in Elgar's case. During the festival we heard more than once how he labored in relative obscurity in his provincial home country up to the age of forty, looking for the success that would open doors for him in London. He broke through with his Imperial March, composed for Queen Victoria's Jubilee in 1897 and dedicated to her. The context and social purpose of this short piece are obvious enough, and it marked the beginning of Elgar's career as a composer of public music, a function which remained important to him throughout his life, one which remains both popular and suspect to this day. His solid domestic reputation began and rested on his Variations on an Original Theme ("Enigma") of 1899 for large orchestra. During the Bard Festival, as during his lifetime, he was split into two characters, the Elgar who composed for strings and the Elgar who composed for brass, as one critic observed. While it is the "string" Elgar, the intimate, melancholy Elgar, who keeps his appeal alive today, particularly in the tense admixtures with the "brass" Elgar which make his symphonies so stirring, the Imperial March helped establish him with the public. In consequence he became one of the few composers who actually made a living through his compositions, and in consequence of that he became, as several have noted, possibly the last great composer to have enjoyed a broad popular appeal. Whether we are listening to one of his two symphonies, Falstaff, or the Cockaigne Overture, we should feel thankful that the man had to earn a living. When we consider hia more dated works, like The Crown of India, it is more difficult to remember that he had few qualms about earning his bread in such a patriotic way.

Through these public works Elgar acted as a pioneer in redefining the concept of an audience. Through his enthusiastic acceptance of the gramophone and later of radio, he was able to reach out into the homes of listeners around the world, a reality we take for granted today. In the 1920's his music was played daily on the BBC. Gramophone records became a necessity of life as much in Canada and Australia as for the British ruling classes in the Raj. Elgar took pride in his records for their own sake and worked committedly with technicians to advance the medium, with impressive results. Yet, while he was conducting Pomp and Circumstance marches in the studio, he was writing such personal works as the Cello Concerto, the String Quartet, and the Sonata for Violin and Piano.

The second weekend, which was entitled From Romanticism to Modernism: World War I and the End of the Long 19th Century began with a symposium on Elgar's broader interests: Charles Darwin and Cardinal Newman: Religion, Science, and Technology in the Elgarian Era. He was in fact a keen amateur chemist and later studied biology. He was also baptized and raised a Roman Catholic, which bore a certain stigma in Victorian England. He was a Catholic, not because of family tradition or because of his parents' conviction, but because his father took a job as organist in the Catholic church in Worcester. This conversion of convenience not only immersed his early years in the music of the Roman liturgy, but contributed to his own feeling of being an outsider throughout his life. It is especially significant that his mature religious works, and even The Dream of Gerontius, in which he set his own adaptation of Cardinal Newman's poem, were intended to appeal to a broad British public, Anglican, Roman, and other recusants alike. The symposium was intended to place Elgar in the context of the two great debates of Victorian England during his formative years, the controversy surrounding Charles Darwin's The Origin of Species and the Oxford Movement, which strove to restore the foundations of the Anglican Church in Catholic liturgy and doctrine, and which led to the conversion of one of its most prominent members, Henry Newman himself.

While the annual collection of essays published by Bard on the occasion of the Festival, this year edited by Byron Adams, is intended as the organ of new research, the symposia customarily bring together scholars in several different disciplines to broaden the context in which the year's composer is to be considered. I'm sure new work is welcome, but, it seems, more often than not the speakers summarize their own past work or their general knowledge with a view to illuminating the topic at hand. One can only wish that the non-musicologists had been encouraged more energetically to spend some time familiarizing themselves with Elgar, for two of them pleaded ignorance of the composer, and this limited the usefulness of their contributions rather severely. This was more noticeable than it might have been because the one Elgar specialist on the panel, Nalini Ghuman, was prevented from attending by unfortunate circumstances I have discussed elsewhere. The symposium was moderated by Deirdre d'Albertis of Bard, a specialist in Victorian literature. George P. Landow, Professor of English and Art History at Brown, gave an incisive account of the Oxford Movement and the position of Roman Catholics in Victorian Britain. Jennifer Tucker, a Professor of Gender Studies at Wesleyan by way of the history of science, summarized Victorian scientific culture and the keen interest taken by the general public in current discoveries. John Picker, a Harvard cultural historian, spoke on the development of sound recording in the 1880's, in particular Edison's wax cylinders, which could be recorded and played by the user of his phonograph. Barringer focused on Edison's London agent, Colonel Gouraud, a flamboyant character, who held sumptuous dinner parties in his home, at which he would ply distinguished guests with drink and encourage them to record messages for Mr. Edison back in Menlo Park. With much speculation about the nature of these recordings, Picker still missed the basic point, that these were essentially epistolary in nature, aural letters, introduced by Gouraud and "signed" by the guest, who was invited to enunciate his illustrious name at the end. Presumably these greats would inspire the public to buy Edison's phonograph in order to send similar missives. This lecture was also something of a missed opportunity, since the genre of sound recording which was relevant to Elgar, the gramophone, really came into its own in the twentieth century. As I mentioned above, Elgar was an enthusiastic pioneer in the medium. This is a fascinating and important topic which was crying out for discussion, since the primary book on the subject is now thirty years old. Lara Kriegel, who has published on the Great Exhibition of 1851, also spoke. Timothy Barringer, a Yale art historian who specializes in Victorian art (among other subjects), made by far the most substantial contribution in his discussion of Elgar's interest in art and of artists based in the Midlands, particularly Worcester. Elgar studied Ruskin's aesthetics and they were important for his work, as the quotation from Sesame and Lilies attached to the score of Gerontius shows. Barringer elucidated this connection by discussing Ruskin's followers, especially Brett, Dyce, and Millais, stressing the role of the direct optical experience of nature in art. Elgar, who was an avid walker and cyclist, claimed that he carried out most of his composing on country excursions, writing his ideas down afterwards at the piano. Especially interesting was the Worcester artist Benjamin Williams Leader, since Elgar kept a print of his landscape of the February Fill-Dyke at Birmingham in the dressing rooms of his various residences in the south. Specific connections like this are most valuable in these symposia, and it is a pity that Dr. Landow and Dr. Barringer were the only speakers to offer them.

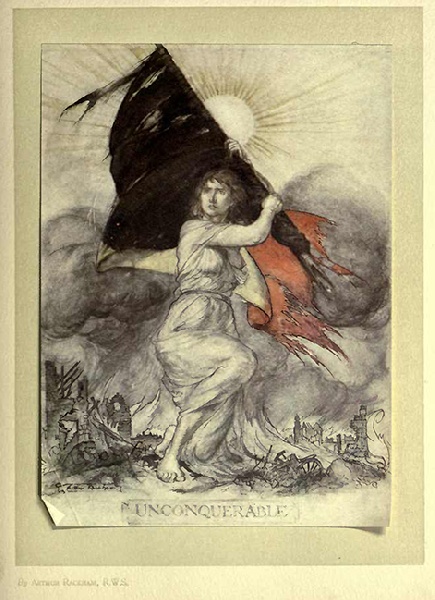

Following the symposium there was a screening of Ken Russell's absorbing BBC documentary of 1962. Produced by Humphrey Burton, who has done so much for music around the world, the hour-long film is a significant document in the Elgar revival of the 1960's. It stresses the more intimate side of Elgar's nature and the conflict between his overt patriotism and the agony of the Great War. The famous trio from the Pomp and Circumstance March no. 1, which he composed during the Boer War, became an especially revered part of wartime propaganda—about which Elgar has mixed feelings. Russell acompanied the stately march with an increasingly bloody montage of WW I footage.

I returned to Elgar Saturday morning for God Bless the Music Halls, a terrifically entertaining survey of music hall repertory organized by composer-scholar Derek Scott, with an enthusiastic and idiomatic all-American cast: William Ferguson, tenor; Thomas Meglioranza, baritone; Gloria Parker, mezzo-soprano; Tonna Miller, soprano. All are distinguished operatic singers still at an early phase of their careers. One may wonder whether anyone heard the precision of their intonation and care in phrasing in the Victorian music hall, but they all had great fun performing the songs, and so did the audience. The program covered a wide range of the various aspects of this popular entertainment, so energetically deplored by reformers: the peculiar symbiosis of the morally improving (i.e. "family values") and the licentious, the character type of the "swell," jingoism and the Cockney. For more about the music hall, see the relevant page of George Landow's extremely useful site, Victorian Web, which will soon include performances of music hall songs..

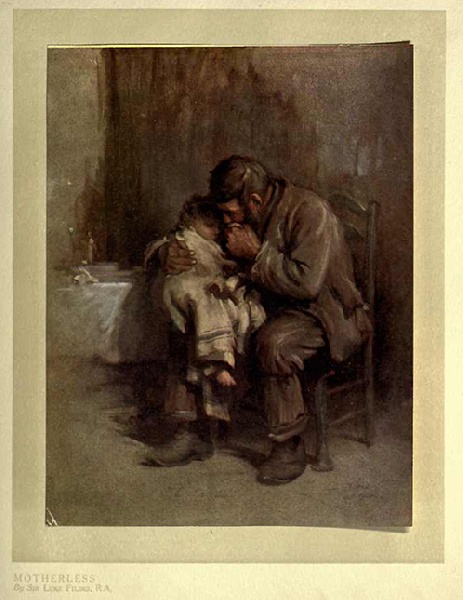

A remarkable program of chamber music, The Great War and Modern Music, followed, preceded by an introduction by Byron Adams, filling in for Alain Frogley, who was indisposed. Dr. Adams spoke with a precision and authority which belied his role as a last-minute substitute. He also used his bully pulpit to fine effect, as he conjured up the horrors of the Great War and its disastrous effect on society and culture, not without a sharp glance at the present situation. The program consisted mostly of chamber works and songs, personal in feeling, which reflected the impact of the War, but it included three works by Debussy and Elgar, which were specifically composed as public statements. Debussy's Berceuse héroique for piano solo and Elgar's Carillon, a recitation of a patriotic poem by Belgian poet Émile Cammaerts, were published in King Albert's Book, an anthology of poetry and music dedicated to the King of Belgium, after his country was brutally overrun by the Germans in 1914. Debussy wrote the song Noël des enfants qui n'ont plus de maison the following year. The quality and sincerity of Debussy's little-known music is astonishing, especially his avoidance of any kind of sentimentality or cheap pathos in the song about children whose homes, churches, and parents have been destroyed by the invaders. In these Ieva Iokubaviciute's sensitive playing in the Debussy was just right, as was Dmitry Rachmanov's virile treatment of the Elgar. Novelist and dramatist Carey Harrison, a local resident, read Cammaert's poem was with gusto and nuance.

Immediate reminders of the destruction of war appeared in music by George Butterworth, who was killed in battle at the age of 31 and in Sir Arthur Bliss' Clarinet Quintet (1931-32), a tribute to his brother Kennard, a gifted clarinetist who was also killed in the war. If one is surprised by the late date of this piece, it is well to remember that it took years for people to assimilate the experience of the war. The first large-scale literary expressions of this experience which were widely found to be convincing did not appear until the late 1920's, for example in R. C. Sherriff's Journey's End (1928) and Erich Maria Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front (1929). Artists and writers continued to come to turns with it right up to the point when concerns about a new war superseded it. It is particularly interesting, I think, to compare this later crop with works produced as the war unfolded, most famously the poetry of Brooke and Sassoon, as well as the music included in this program, Ivor Gurney's intensely felt elegies (1913, 1917), John Ireland's powerful Piano Trio No. 2 (1917), and Elgar's Violin Sonata in E Minor of 1918.

The violin sonata belongs to the group of chamber mastepieces composed in the seclusion of Brinkwells, a cottage Elgar's wife, Alice, had found in Sussex, when the stress of wartime London became irksome for him. Here Elgar was close to nature—but also close to the war: when it was quiet they could hear the big guns from over the channel. Elgar chose to dedicate the piece to a German friend, showing another dimension of his distress with the war. His formation was immersed in German music; he had traveled in Germany, attended many concerts, and had enjoyed warm success there; and to find himself on the other side of this hideous conflict from his German friends was deeply painful for him. Like the other late chamber works and the Cello Concerto, the violin sonata encompasses a vast emotional range. It is heroic music, but also intimate and dreamy, full of the feeling for nature that was so much a part of Elgar, "wood magic," as Alice called it. The young violinist Jennifer Koh tackled the work on a grand scale, propelling it forward with muscular energy and projecting a big sound. While this was certainly legitimate, I could not help feeling that her expertly turned observances of Elgar's more reflective moods did not go much beyond the intellectual. Koh's athletic sweep tended to overwhelm Iokubaviciute's subtle playing, which seemed more sensitive to Elgar's emotional transformations. The knowledgeable Olin Hall audience responded with enthusiasm, and I have to agree that Ms. Koh is an impressive musician, but the hermetic core of Elgar's music was undeniably shadowed over in her performance.

Ireland's Trio no. 2 was played by The Claremont Trio, a group of extraordinarily gifted very young musicians, Emily Bruskin, violin; Julia Bruskin, cello; Donna Kwong, piano, U.S. First recipients of the Kalichstein-Laredo-Robinson International Trio Award. They played the slow introduction, beginning hauntingly in the cello, joined successively by piano and violin, most beautifully, with fine tone, control, and feeling for its elegiac mood, and carried on very convincingly through this dark, complex piece by a war-ravaged composer.

American baritone Weston Hurt gave a lovingly prepared, deeply moving account of George Butterworth's Six Songs from a Shropshire Lad, a setting of selections from A. E. Housman's celebrated collection of poems, in its way as much of an English institution as Land of Hope and Glory. Hurt's baritone voice, with its leathery depths and tawny highlights, is a superbly balanced instrument, and he presented the cycle with dignity, taking full responsibility for its seriousness, with disciplined phrasing and sensitivity to its changes of mood. Of all the performances I heard at the Elgar Festival, I found this the most affecting.

Arthur Bliss' Clarinet Quintet is both touching in its elegiac moods and intellectually fascinating for its brilliant compositional invention. It is striking how Bliss introduces instrumental solos only to enrich them with other voices within a few bars, creating a work extremely rich in texture. It is also not without its Elgarian moments, always updated to the more pungent taste of the early thirties. The Bard Festival String Quartet and Laura Flax, clarinet, were absolutely superb in this music.

Apart from its context within the Elgar Festival, a program of British chamber music of this sort is a fine thing in itself. What does it take to attract a decent-sized audience to such an event in New York or Boston?

Saturday evening, Leon Botstein, the American Symphony Orchestra, and an enthusiastic audience gathered in the Sosnoff Auditorium for a program, entitled Elgar: the Imperial Self-Portrait, which included three of Elgar's finest works for orchestra and one questionable one, his Crown of India Suite, Elgar's concert adaptation of his incidental music for the "Imperial Masque" lavishly staged at the Coliseum in 1912 to celebrate the Delhi Durbar of 1911, in which George V and Queen Mary became the first reigning British monarchs to visit India. Quite probably the grandest public ceremony of the twentieth century, its purpose was to celebrate their coronation as Emperor and Empress of India, and it was attended by virtually ever prince, noble, and person of note in India. London responded with numerous elaborate celebrations. While Elgar and his collaborator, Henry Hamilton, conjured up the Jacobean masque, presentations in the new cinematic medium were also offered, including a two and a half hour film in Kinemacolor, With our King and Queen through India. Nalini Ghuman's excellent article in Bard's collection of essays goes through the background of The Crown of India in fascinating detail. As much as many of us deplore such triumphant imperialism today, it is easy enough to join in the fun at our historical distance. The Pomp and Circumstance marches, whatever embarrassment they may have caused in London at various junctures, even to Elgar himself, are by not museum pieces yet by any means. Nonetheless, I found this music slightly repellent in itself, perhaps because of Elgar's rather finicky, even queasy, handling of exotic motifs. In the March of the Mogul Emperors, they do not march, but proceed to a polonaise rhythm. It is as if Elgar could only bring himself to touch the music of India with white cotton gloves on. Yet, the music from The Crown of India, especially the march, was, like the masque at the Coliseum, immensely popular, as early performances and recordings indicate. Specifically the march was a hit at the "great patriotic concert" held at the Royal Albert Hall in 1915, along with, of course, Land of Hope and Glory, where it was performed by 400 musicians selected from army recruiting bands. Elgar detested such popular entertainments as vulgar, and even his thoughts about patriotic sentiment began to waver.

In Sosnoff's vivid acoustic Botstein and the ASO played the suite with all the color and spirit one could desire, although more familiarity or rehearsal might have elicited more of the subtleties of Elgar's orchestration. In general the ASO seemed to have settled in and were playing with more precision and agility than the previous weekend. They were certainly able to give their best to Elgar's lovely Sospiri for strings, harp, and organ.

In his "symphonic study" Falstaff (1913) Elgar brought together everything that was most characteristic of his personality as a composer, rich thematic material, vigorous narrative, vivis character studies, strong counterpoint, and colorful orchestration. Sir John Falstaff appealed to him at a deeply personal level. Whatever flawed aspects of his character might appear, Sir John remained "a knight, a gentleman, and a soldier." Hewing to Henry IV parts I and II and Henry V, created a Falstaff as unforgettable as Verdi's quite different Falstaff drawn from the Merry Wives of Windsor. This long, complex single movement was Elgar's supreme act of the imagination, but, in order to bring it to life, the conductor and the orchestra must command the full range of the composer's tonal palette as well as a subtle rubato to support the rapid alterations of mood and expression. As usual, Botstein produced an energetic reading of great dynamic range and clarity. It was valuable to hear every line stand out so clearly. However, color, emotion, and a sense of Elgar's narrative flow and characterization were entirely lacking. Amazingly, the deeply moving final passage depicting Falstaff's rejection by his beloved Hal and death fell flat.

The Second Symphony fared somewhat better. In this symphonic work the clarity and coherence of Botstein's approach was of more value, but still not nearly enough. Without a sincere imaginative sympathy for Elgar's emotional world, energetic gestures count for nothing. The Second is a symphony which is both a grand public statement and a reflective, internal one. Botstein and the ASO seemed incapable of the tonal atmosphere necessary to bring this across. Perhaps the Second is not so different from Falstaff, after all. The Bard musicians achieved their greatest success in the slow movement. The simpler, more delicate textures seemed to make everyone relax and lose themselves in the music for a good part of the movement, but eventually even this wore out. The scherzo was colorless. The finale spun its wheels and flirted with bombast. On my way to the parking lot I overheard a woman, who had not heard the symphony before, complain of its monotony and incoherence. As more than one of the speakers pointed out, Elgar is not "performance-proof." Even his "absolute" music reflects a Wordsworthian logic of emotional contrast and development and depends on sympathetic expression for coherence as it unfolds. In fact there are critics who find Elgar lacking in construction and consistency, while convinced Elgarians admire his consummate skill. In analysis or performance, I believe, it is a matter of whether one can go beyond the literal notes and see how they fit together in the imagination, or not.

Botstein's approach seemed entirely too "mitteleuropäisch" for Elgar, although we cannot forget that Elgar and his British predecessors and contemporaries were steeped in German music, above all Mendelssohn, Brahms, and Wagner. Dvorák was also a highly respected visitor. Elgar's music enjoyed some of its first successes in Germany. The shortcomings of this evening at Bard point out what is perhaps the crucial question about Elgar's music today. Most agree that Elgar is one of the very great composers, with Purcell, England's greatest. Yet his music is not as well known as it deserves to be outside Britain, and I have to admit that most of the satisfactory performances of his orchestral music have been by British orchestras under British conductors with exceptions like Hatink, Previn, and, a wonderful performance I heard on tape from the mid 1960's of Elgar's Second Symphony by the Boston Symphony—under Barbirolli! It has been observed that whatever Elgar's fortunes among the public and among critics, British musicians have consistently loved playing his music from decade to decade. They have developed a tonal and expressive vocabulary which can communicate its organic poetic structure. Colin Davis, who once disliked Elgar's music, is now performing it avidly and has become one of its most respected interpreters. In his performances he cultivates a brighter, more astringent sound and more urgent tempi, and these project a more international character. Sir Colin appears to be consciously promoting a less "English" style of Elgar performance, and this may open the door wider international performance. The limitations of the Bard performances underscore the present situation.

Is internationalism the key to full acceptance as a cultural hero? This is most likely a fallacy. Germans already regarded their music as an international standard by the early nineteenth century, taking the crown from the Italians. But by mid-century, the "New German School" included a French and a Hungarian composer. England, which at that time suffered from a musical inferiority complex, turned to Germany in an adulatory spirit. As the first weekend's concert of orchestral variations by Parry, Stanford, and Elgar showed, Elgar was able to free English music from German doctrine and to create a freer, more poetic and psychological musical language, which was inherently expressive of the national character. It is interesting that this occurred at a time when the British Empire was at its apogee, connecting Britain with colonies and dependencies all over the world. While an Elgar received Indian culture in his own "very English" way, pupils of Max Müller could immerse themselves in ancient Sanskrit writings as never before, and the sahib could enjoy his curry or his overcooked fish and peas à l'Anglaise at his pleasure. Whatever came to London, there was little motivation to export Elgar's music beyond the gramophone records so much prized in places like Melbourne and Bombay. Elgar's four American tours seem to have made little lasting impression.

Perhaps if Botstein and the ASO were to return to this repertory again and again over the years, they would assimilate its language, but that is not the way they work. But in fact I have few qualms about my harsh judgement of Saturday's concert after coming back on Sunday to hear The Dream of Gerontius, preceded by a few snippets from The Kingdom. This was a glorious event, free from any of the problems I experienced on the previous evening. Perhaps its very basic and universal spiritual content, the progress of the soul towards salvation, or the participation of vocal soloists and chorus, which created a tangible, almost stage-worthy drama, made the difference. Mr. Botstein's performance was totally absorbing and convincing from beginning to end—and deeply moving. The preparation was impeccable, perhaps most impressively in James Bagwell's outstanding work with the Bard Festival Chorale. The soloists were very fine indeed with Jane Irwin a monumental Angel, John Hancock a vivid and forceful Angel of the Agony, and Vinson Cole a thoroughly convincing Gerontius. Cole's light, humane tenor voice is somewhat reminiscent of Peter Pears. He sang his part like a master, reflecting extremely thorough study of both music and text, and his beautiful phrasing did justice to both. Botstein seemed captivated by his singing and attentively kept the orchestra in balance with him throughout. Jane Irwin's large, crystalline mezzo-soprano only made her seem all the more of another world. Clear-textured as usual in spite of the huge forces, this was a performance of sweep, power, and operatic drama. The audience, transfixed, was one of the quietest I've heard in these parts, until their opportunity to show their appreciation arrived at the end.

Whatever shortcomings the Elgar Festival had were at the very least instructive, and the conclusion of this summer segment was triumphant. We have now the weekend in late October to look forward to, with a panel discussion on anglophilia and imperialism, more Ireland, Bridge, and Vaughn Williams, more Pomp and Circumstance, Elgar's lyrical ballet, The Sanguine Fan, and his First Symphony, as well as Sir Colin Davis' performance of The Dream of Gerontius with the BSO in January...and beyond that, the 19th Annual Bard Music Festival, which will be devoted to another composer who suffered from conflicts between his public and private roles, Sergei Prokofiev.

---

ERRATUM For more on Elgar, including bibliography, see Victorian Web.

In the second to last paragraph of my report on the first weekend of the Bard Festival, I mentioned a valuable insight into the Enigma Variations, according to which "each variation, most bearing the initials of friends, express the composer's personality through the consciousness of his friends, a quintessentially modern artistic gesture," and I attributed it to Diana McVeagh, who cited the opinion in her talk, making it clear that it was the view of Byron Adams. Through hasty compression I neglected to report this, and I apologize both to Byron Adams and Diana McVeagh.

For more on Elgar, including bibliography, see Victorian Web.

For more on Elgar, including bibliography, see Victorian Web.

For more on Elgar, including bibliography, see Victorian Web.

---

Web: http://michaelmiller.goodletters.net

e-mail: heliagoras@gmail.com