Summer HD Festival in Lincoln Center Plaza - Part Two

Encores from the Metropolitan Opera

By: Susan Hall - Sep 08, 2009

Peter Grimes by Benjamin Britten, Public Showing, Thursday, September 3, 2009 in Lincoln Center Plaza, New York.

Madama Butterfly by Giacomo Puccini, Public Showing, Monday, September 7, 2009 in Lincoln Center Plaza, New York.

Benjamin Britten is arguably the greatest of 20th century opera composers and Peter Grimes his masterpiece. The new production of Peter Grimes at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York is masterful, and one selected for HD transmission. Last Thursday, it was reprised in Lincoln Center Plaza as part of the Met's inaugural summer HD series. With a full moon reflected in the windows of the opera house, dramatically obscured from time to time by stormy black clouds, all of the opera's intensity was magnified.

Serge Koussevitsky had commissioned Peter Grimes (for $1000) to be performed at Tanglewood in 1944, but the entire Tanglewood season was cancelled that year due to war. The opera had been composed by Britten and his longtime partner tenor Peter Pears in Escondido, California, after they'd come on a poem, "The Borough" by George Crabbe while scavenging in a second hand book shop. The poem is set in a town very much like the one in which Britten grew up, a harsh fishing village on the east coast of Britain. If the opera seems cruel and hard, the Crabbe poem is even more so.

Pears was the original Grimes, and brought his beautiful lyric tenor to a character whose artistic temperament is battered by a town full of ignorant dolts. When Jon Vickers took the role on in the early 1960s, he saw something else in the music and libretto. He brought a ferocious temper and cruelty to the role (which Britten is said to have hated, perhaps because it came too close to a piece of his own nature).

Anthony Dean Griffey, taking on Grimes, chose not to listen to any prior recordings, films or DVDs of his predecessors. He wanted the role to be his. Unwittingly he combined both past interpretations to wonderful effect. Griffey is a bear of a man, but his lyricism in arias like "Now the Great Bear" is sweet and mysterious, in contrast to the ferocity of his voice when he is enraged, or its intensity and passion in the mad scenes. Volatile, confused, modern, we understand this Grimes, as uncomfortable as Griffey's performance makes us.

Patricia Racette's warm presence as Ellen Orford, the school teacher who is Grimes' hope for salvation, helps us understand why she is attracted to him -- ever hopeful, as teachers are, for progress and change. Other sopranos have presented dry, wisened school marms and left us wondering why Ellen cared for Grimes at all. Racette offers help to the tormented man, but in the end is cast off by his wildness. Her rendering of the 'Embroidery" aria is wrenchingly beautiful.

Two other big characters fill the stage. One is the chorus, conventional townspeople growling and hissing Grimes' name like Salem residents crying, "Witch." The other, the sea itself. With four sea interludes, this character echoes Grimes' own -- a force of nature, at times pacific and calm, at others, raging and uncontrollable.

The set for this production caused much comment, some critics assessing its looming presence stage front as too dark, too big, too discomfiting. Quite the contrary, it is perfect for this opera. Other productions have included seaside scenes in which real boats were hauled up with superhuman effort by the singers.

The claustrophobic effect of the building's wall mirrors the mood of the borough. When the wall opens from time to time to reveal a tavern scene or the sea itself, we let out a breath. Still this giant wall can't hold back the force of nature -- whether it's Grimes or the sea. In the great 16th century Dutch maritime paintings, the setting always points in the direction of the story, and here, the massive building in its bleak darkness foretells a tragic ending.

How unlikely it seems today that Madama Butterfly would have been greeted by cat calls at its premier while Peter Grimes, the less accessible opera, was greeted with silence and then 14 ecstatic curtain calls. Puccini had been running behind on the composition and it would take three months of performances in many Italian opera houses to mold the opera into the version we love so today.

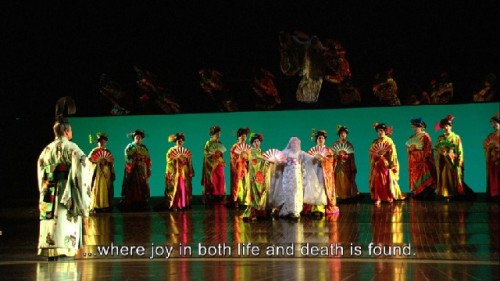

Anthony Minghella first mounted this "Butterfly" in London and it dazzles the eye. Patricia Racette's performance tugs at the heart from her first tiny steps across stage to meet her husband-to-be. Her emotional range extends the range of her voice and it is no surprise to see an audience in tears when she is inevitably betrayed.

Having watched and listened to Racette only days before in "Grimes" I was struck by the warmth of her voice and performance. Her beautifully shaped arias (and duets and trios) all resonate, but the very real humanity she conveys on screen is unusual. Marcello Giordani as Pinkerton and the rest of the spot on cast make this production of "Butterfly," whose visual effects are stunning, a treat.

In the back of the "Butterfly" stage is a rectangle, colored in an intense red and then brilliant blue. It contains an horizon over which all the characters enter. The small house Pinkerton has rented for Butterfly (for 999 years, contract cancellable at anytime, just like the marriage) makes us feel how delicate and protected her world is.

Some have complained about the puppet who plays Butterfly's and Pinkerton's son. Even though I knew he would appear, I was surprised by his compelling face, at once winsome and yearning. Manipulated by puppeteers whose own expressive faces could be read through veils, I was moved. Of course it helped that Racette doesn't miss a beat in her motherly embraces.

This beautifully fresh production goes a long way to bringing the opera to our own time, although our imperialist impulses, a subtext in this story, have been mercifully held in check.

Who is behind the filming of these productions? Clearly someone who understands music as well as drama. Gary Halvorson, director of the HD for both "Grimes" and "Butterfly" was trained as a classical pianist. I was not surprised to discover this, because his cameras are used as lines to accompany the music.

In an interview with the Met's Elena Park, Halvorson talks about making productions clear enough for his mother in Minnesota to understand. Halvorson comes to us via TVsitcoms and an Emmy for the direction of the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade. He apparently scripts the cameras movements, but will improvise if a performer, whose actions you can never predict, does something interesting. "I play by the seat of the pants," he says. This risk-taking brings excitement to the HD whenever you watch it.

These encore transmission seemed very present -- a new and extremely satisfying experience of the opera. Bravo Met!