The Dishwasher Dialogues, Fascist Francisco Franco

Chasing Immortality

By: Gregory Light and Rafael Mahdavi - Sep 10, 2025

Cleaning for San Fernando

Rafael Mahdavi: At Chez Haynes, it was warm in the winter, and we were fed; these were two buffers against hardship. And if I indulged in feeling sorry for myself, Alicia, the Spanish cleaning lady at the restaurant, always lifted my spirits. She and I crossed paths every evening; she was finishing her cleaning as I arrived. As I set up the bar and washed glasses, we chatted in Spanish. She was from Sevilla and was married, and her husband worked the night shift for the French railroads, the SNCF, Société National de Chemins de Fer. They had come to France as a newly married couple, to get away from Franco, and now they were in their forties. Some evenings, just like that, Alicia or I would say ‘that Bastard Franco finally died’. He had died in November 1975. (Francisco Franco).

Greg Light: That Bastard’s Guardia Civil beat me up on one of the less savory streets of Barcelona in late 1971. That scared the living daylights out of me.

Rafael: Alicia called him el cabrón de Paco Franco, the Billy goat Paco Franco.

Greg: Much too kind an epithet. I assume it conveyed a more scathing humiliation of the old dictator in the Spain of the time. It does not capture my memory of Alicia. Quiet and understated. If you had not mentioned her, I am not sure she would have come easily, or at all, to my mind.

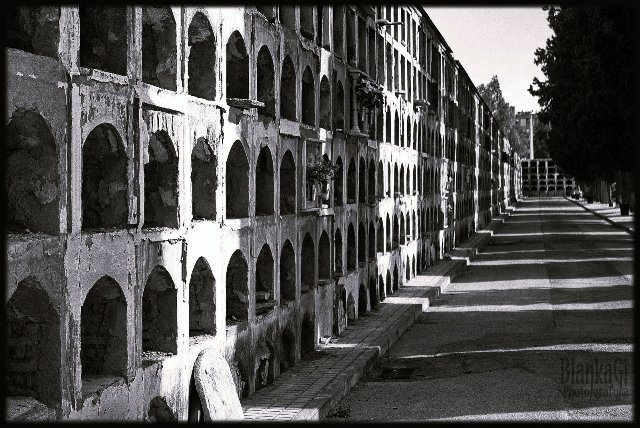

Rafael: During the day, before she came into the restaurant, Alicia cleaned fancy apartments in the sixteenth arrondissement in Paris. She looked worn out, her face was prematurely lined from years of exhausting work, but when she spoke Spanish, her face lit up. She was always in a good mood. One evening she told me she and her husband were planning a visit to Sevilla to see her relatives, but the real purpose of the trip, she confided, was to buy a plot for herself and her husband in the San Fernando Cemetery. How about an apartment first, I asked her. First, we serve God, she said. She loved bullfights, and she had only been to the Fair of Sevilla once in her teens. Rarely did she mention her daughter, who was her cross to bear. Why? ‘She sleeps around, Alicia’ said, ‘and seems to have a lot of money all the time’.

Greg: I want to say Alicia was an inspiration, but I do not think I would have said that then. Nor now. I remember she worked incredibly hard and did not complain. At least not to us. I could not speak to her in Spanish, and I think her French was about the same as mine so our conversations were full of head nods and smiles, the kind that said we would both appreciate getting to know each other a little more if the curse of Babel permitted. But it didn’t. I do remember her referring to her teenage daughter on more than one occasion. Even in our threadlike exchanges, I could see it was a troubling preoccupation, and that her smiles and nods could only suggest there was a deeper story there.

Rafael: I mention Alicia because she was a reminder not to complain or feel sorry for myself. And if she was ever depressed Alicia never once let it show. To this day I think of her often and I hope she and her husband did buy an apartment in Sevilla and retired there. But by now they’re probably with San Fernando.

Greg: Realizing the eternal peace of her first investment? My overwhelming sense of Alicia as I think back now is how cheerful she was. Never a mean word or nasty gesture. Always smiles. And you are right, she was a reminder of how fortunate we were back then. Despite our lack of money, we chose it. But we had support systems, not the least of which were our education and privilege. We could pursue idiocy and call it experimentation. While we aspired to whatever nonsensical ideas of artistic immortality prevailed back then, Alicia aspired to a cemetery plot. I could have learned a lot more about things that matter if I had been wise enough to stop a while and listen more carefully. But wisdom was not abundant back then.

Rafael: At Christmas, Leroy gave her two thousand francs as a bonus. That was a lot of money in those days, about 400 dollars.

Greg: That was pure Leroy.

Rafael: The lack of money sometimes triggered depressions and feelings of failure in me. But it was seldom debilitating. At the restaurant, we rarely talked about our feelings. The work at Chez Haynes kept me busy, there was little time to mope and whine. I talked about my painting. You spoke of your poetry and your plays. We didn’t realize it then, but Chez Haynes was an antechamber of sorts or a safe zone where we worked on the first moves to pursue our dreams. A few years later, I understood this when there were no more safe zones, and depression became a recurring beast in my psyche.

Greg: And San Fernando beckoned.