Clark Launches New Galleries with Make It New

Selection of Mid Century Abstraction from the National Gallery

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 11, 2014

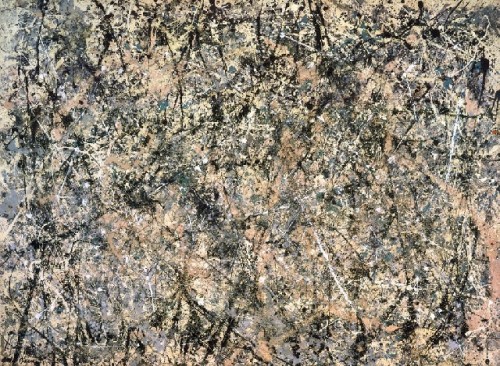

Launching the new generously scaled special exhibition galleries designed by Tadao Ando is a selection of 35 abstract paintings by 35 artists from the National Gallery of Art curated by Harry Cooper. It remains on view at the Clark Art Institute through October 13. The Clark is the only venue for the exhibition.

The Clark's curator David Breslin worked closely with Cooper on the project. He contributed catalogue entries on the works along with Matt Jolly.

There was a one day seminar Make It New? Cinversations on Mid Century Abstraction organized by Darby English, Starr Director of Research and Academic Program.

We spoke at length with Breslin about this unique step into the 20th century by the traditional Clark. This is the first of two parts of that dialogue.

Charles Giuliano The Clark’s special exhibition Make It New: Abstract Painting from the National Gallery of Art 1950-1975 evokes different experiences. There is the direct, sensual viewing of the large scale works installed in a pristine, almost antiseptic manner in the new galleries designed by Tadao Ando. How is that directly involving visitors? Then there is the more complex approach to the catalogue essay by the curator Harry Cooper which is dense with art history, theory, and a summary of critical thinking about the Post War era of art and its progeny. Uniquely, Cooper frames the discussion on an armature of several categories developed by Harold Bloom. It was applied to generations of poets and the nature in which the forms and concepts are transmitted through poets that follow. How, for example, did artists who develop from the twin peaks of Pollock and de Kooning take from them as well as derive their own unique works?

The selection of works seems so meticulous that it suggests that it is organized to make a specific didactic point.

David Breslin It’s interesting to me that you see it that way. Whatever our intention was be damned but the hope was by creating a format where you had two galleries that are based around historical periods, movements or schools.

You can see in some ways how art history has inscribed to have particular groups of artists stand together. Even thought the abstract expressionists knew each other, drank together and had a lot of the same concerns their works in some ways couldn’t look more different.

The Color Field artists while they trafficked between D.C. and Bennington a lot of their work has many, similar, visual characteristics. Even though they couldn’t be more different in how they arrived at them.

Then when you get to the three galleries which are based around formal concerns maybe didactic is a good word for it. For the viewer to teach herself what sometimes art history leaves out. Which is, you can make these visual connections that haven’t already been determined by somebody else.

Putting Alma Thomas next to Marcel Broodthaers isn’t something you would see at most places. I don’t think that Harry (Cooper) would install them that way at the National Gallery. Because it doesn’t fall into a particular historical story. Perhaps they wouldn’t have known each other. The works deal with very different things. Putting them next to each other allows us to ask, well, what do they have in common? If we want to talk about differences articulate what those differences are. Besides just one’s from Belgium, one’s from Washington, D.C. One was a black artist working within the Washington Color Field tradition. One was a European artist thinking about nationality and different institutions after World War II. Ok, that’s fine. But the fact that they both chose to cover a surface with things that aggregate into intense visual pattern. Why would these people do that?

My one hope for the show is that it’s not antiseptic. By putting some of these funkier works on display that it messes up the narrative that abstraction is cold. That it’s hermetic. That it’s for a certain kind of people already in the know.

CG The 500 pound gorilla not in the room is de Kooning.

DB Yup.

CG (Laughing) Can you elaborate on yup?

DB To be honest the National Gallery doesn’t have a great abstract de Kooning. We really deal with what we had. There are a handful of works we borrowed but they’re just from (living) artists. Like the Jasper Johns painting. The Target painting. The Stella Delta painting which has been on long term loan to the Gallery. So, no de Kooning, yeah. It’s a big deal. The longest footnote in the catalogue by Harry is a laundry list of people that he would have wanted to have included or couldn’t include just because of working within what the National Gallery has.

That being said the Gallery is getting a number of great abstract de Koonings. He didn’t want to include a Woman painting (by de Kooning) because this was a concerted effort to use things that didn’t have a direct reference to the figure or very direct reference to the landscape. That’s why we chose the Frankenthaler Wales painting and not Mountains and Sea.

CG That skews the argument into a specific direction. It denies the fact that figuration and abstraction existed simultaneously in the works of many artists of the era in question.

In the catalogue I noted Cooper’s argument that Mountains and Sea was too literally a landscape. It seems unfair however to include Pollock’s masterpiece Lavender Mist and not Frankenthaler’s (which is on extended loan to the National Gallery). It is the painting by Frankenthaler that opened the door for the Washington Color Field school.

Leaving her masterpiece out, as well as not including de Kooning, leads to why I say that the exhibition is antiseptic. (Presenting a controlled and monolithic take on mid century American abstraction.) The selection is skewed to make a particular point and critical argument.

Of course this semantic issue is lost on the general visitor to the Clark who is encountering a major exhibition of 20th century abstraction in a museum noted for its depth in French impressionism.

DB That’s a very fair point. I think in some ways we could even conceive of Harry’s essay for the catalogue as something that reflects on the show but isn’t really the argument that the exhibition is making. If that makes sense. He really wanted to give an account of what Post Pollock painting could be.

That one Pollock painting is there and it is obviously such a canonical piece and really directs how we look at the exhibition. I don’t think anything in the show itself and one’s encounter with the exhibition leads us to think of Pollock only as the way in and out. The essay does that but I wonder if the exhibition does.

There are 35 works in the exhibition by 35 different artists. Harry’s essay gives a way of looking at what a post Pollock exhibition is. The exhibition itself is kind of like each artist gets a vote. For what direction he or she took things in.

The essay has a very definitive point to view. You’re absolutely correct about that. Whether the exhibition does is another question.

CG You contrast the homogeneity of the Color Field painters with the diversity of the Abstract Expressionists. Yves-Alain Bois in his remarks avoided any of the social history of the era. I asked him about the messy stuff surrounding Sandler’s Triumph of American Art, Guilbaut’s How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art and MoMA’s New Images of Man. The era was far more complex and messy than we see here. Bois and other mainstream historians want to eliminate the edges and look only at the center.

The Abstract Expressionists were combative.

DB Truly.

CG How can you apply a single term, Abstract Expressionism, to artists as diverse as Pollock, de Kooning, Motherwell, Reinhardt, Newman, Rothko, Stamos, Gorky, Baziotes? Particularly Gorky and Baziotes are connected to surrealism as is Matta. The term lumps them all together. Then, of course, we fudge by calling them New York School.

DB Yeah, right, exactly.

CG But when we say Color Field or Formalism we know exactly what we mean. Is it Color Field Painting or the School of Clement Greenberg? Consider how he took Louis and Noland to Frankenthaler’s studio to show them Mountains and Sea (in her absence). Here, look at this.

DB Exactly.

CG They got their orders to go back to their studios.

DB This goes directly to the decision to organize those three other galleries. In ways that avoid school or movement. You could have thought about a gallery of quote/ unquote Hard Edge Painting. Or Process Painting or Arte Informale from Europe. But the very issues that you bring up that there’s critical short hand to put people together because we want to group people, there’s an organizing thing to want to push people together that aren’t necessarily perfect neighbors. By putting together, at least for this exhibition, three rooms that avoid movements or if the movements are there also trying to compound what’s there in a pretty short period, 25 years, it isn’t that long. So in some ways to also resist the idea that movement determines all, you give the idea that it gives a lot of respect and attention back to individual artists. And how he or she works within the particular period with particular people. So we’re on the same page with that. The exhibition does that thing. It allows people to get a sense of what was happening within the period in terms of what was happening and how critics and art historians look at it. Having those two rooms of Abstract Expressionism and Color Field Painting almost in quotes and then see these other things in a way that does not automatically and reflexively goes back to a title that somebody else gave them.

CG What are your thoughts on the seminar which accompanied this show?

DB I think it was very successful. It was an activity with people who are engaged in making abstraction thinking back about the period and the work they are making. In some way to get out of received information.

Yves-Alain I respect a lot but to have a series of lectures in the same way would defeat what we wanted to do. Which is to say what are you looking at. Glenn Ligon had this moment with de Kooning I think is important to enter into a new historical record about lineage, about misreading (Bloom’s term) what people got out of people who came before them and what they didn’t. In that regard it was a great success. I like the format that permits accidents to happen. Like when Marden was talking. What was his term?

CG Cheap Shots.

DB It’s great to have a format where an idea like Cheap Shots comes out. That makes it a successful thing. If we can be there and think along with the people on the stage that’s great.

CG Did you read my piece on Marden that came out of the Symposium?

DB I did. I think Marden is an important artist and I think you get to how, I don’t know how important it is, but the range of influences going through that work.

I was interested and wanted to ask you, you almost seem to put Ligon and Byron and Sillman and Eggerer together almost as a set of artists who are completely different from Marden. I wonder in your thinking whether that’s a generational thing?

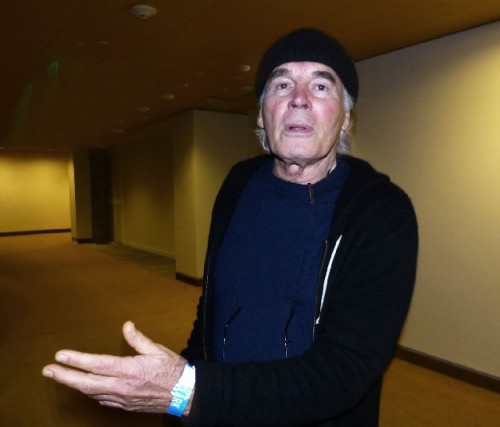

CG It’s fair and interesting that you ask me that. You’re entitled to put me on the spot about it. I accept that. I’m 73 and Brice Marden is 75. He’s kind of a hipster.

DB (laughing) Yup. In the original sense.

CG Truly. And I come from that. Particularly when I was able to grab him in the hall there was a sense of immediacy. There was no need for an introduction we got right into it. Kind of a high noon exchange of gun slingers trading shots. For me it was exhilarating. I felt compatible and would love the chance to talk with him in depth. You have to catch people while you can. I felt a total comfort zone of how I saw him as an artist. His genuineness. The persona. It was a complete experience.

Generationally? Yes. I can totally identify with that. For me there is a problem. If you go back to the Abstract Expressionists there’s a whole cultural phenomenon. It’s about everything of that era, the art, the music (jazz), the literature (Beats), and movies, theatre. The term has been used to describe The Great Generation. If you go back and look at the totality of the era and experience of World War II and its aftermath, at every level, social, political, economic, cultural, there’s a real sense of combat and battle, of struggle. In art Sandler talks about it Guilbaut talks about the art world's center moving from Paris to New York. There’s such a huge, historical, seismic shift from one side of the Atlantic to the other and the embattled way that these guys came out of that. There’s an oracular quality to that generation.

DB I agree.

CG There’s an authenticity and intensity. If you walk into an exhibition of MoMA galleries of that generation there’s a visceral response. It hits you in the stomach.

Then I listen to Amy Sillman. Give me a break. Describing drinking with ‘the girl’ in the bar (during the symposium) and describing rubbing on her friend (using Eggerer to demonstrate) describing a de Kooning brushstroke and then describing the machismo of Pollock “flecking” paint in a hostile, aggressive, macho manner. I found that absurd and comical. I don’t believe it. I’m offended by it. I find it annoyingly superficial. I find it arrogant. Unfortunately that’s a lot of my take on current work. Perhaps when they get to be 75 they might think differently.

Last night I was watching a PBS American Masters segment on the photographer Dorothea Lange. At that point she was elderly and in poor health. It focused on efforts with John Szarkowski to curate her retrospective at MoMA. (She died before it opened.) I was astonished by the struggle and intensity of her work. Its risk taking and commitment. Her experiences during the Depression and what she was looking at. The integrity of her work.

I don’t find that intensity filtering down to the current generation (of art stars). Sitting in the audience I felt careerism and art speak. More smartness than feeling. Compared to this wizened old gun slinger. Wacky, eccentric, crazy and doesn’t give a fuck what anyone thinks. My kind of guy. Speaking with resonating authenticity. Where I felt that the other artists in the symposium were telling me that they’re smart.

DB I agree about Marden. He knew a lot. He should have been in that show. If the NGA had his works. That’s another issue where the ( Robert and Jane) Meyerhoff Collection has great Mardens going to the National Gallery. If the show had been two years from now his work would have been included in the exhibition.

But to your point there was such a rupture caused by this Greatest Generation. To come after them, a lot of what you are articulating happened in the cracks that came after a huge earthquake.

A lot of what I took from the other conversations (of the symposium) isn’t so much trying to kill the father again but understanding where the father was coming from.

CG Going back to Cooper’s essay, in his context of Bloom’s criteria, where would what they are doing fit into that index? Are they misreading their artistic ancestors?

DB If they are misreading it’s a purposeful misreading. Obviously, there were conversations about canon going on. Who gets included. Yes there’s a lot of great stuff that happened with that Greatest Generation. But there are only so many people who got to speak as part of that. Talking about women, people of color, artists who could be openly gay and have that be part of how they work. Whether it goes into the work or not is another question. To have just as much personality present as the gun slinger. I think that’s an important thing. Whether it reflects how one makes art or not is another question.

It’s a matter of training. These people are coming a generation after critical theory so they’ve been bathed in that and it’s a part of how they think.

Bois brought this up but the fact that Amy Sillman is in a bar talking about Pollock and de Kooning in 2014, I saw that not as denigrating the importance of these people, but the fact that they live on. How do they live on? They’re still a part of the dialogue. Part of an artist living now, her scene and what she does. I think if it were to be reverential that would be totally boring.

(As Sillman commented, paraphrasing, we all saw the movie, right? With what’s his name? –audience answers- Ed Harris.)

CG In summation remarks Bois debated Sillman’s comments about Pollock’s aggressive, macho flinging of paint. He commented that Lavender Mist is lyrical and poetic, an intricate spider’s web.

It underscores the problems when you apply biography to the work of the artist. Based on the persona of Pollock, as portrayed by Harris, Sillman sees him as aggressive and macho. If you look at the work itself it has a different impact. Critics discuss his brilliant drawing directly onto the surface of the painting. A ‘misreading’ is to be influenced by the persona of Pollock and then see that in the painterly gesture. The choreography of how the paint is applied and then just assume that there is a machismo about it.

DB Right. I think we can see the lyrical with the aggression (Blue Poles). These things coexist for me in the paintings. It’s important for someone to bring up the aggression and it’s important for Bois to bring up the lyricism. Just as it’s important that there was a lot of doubt in abstract painting. A lot of decisiveness about what a picture is.

To have these conversations lets us not close off a definitive way of reading these things that enriches how we view them now.

For us to rethink these things now isn’t just to repeat the stories. But like any good story teller is always trying to transform what’s happening at that particular moment in time or history in the retelling of that story.

CG I hope not to paint myself into a corner. In transcribing this perhaps I will end up eating my own words.

DB (Laughing) I will too so give me a chance to do that.

CG My attack style of journalism means that I often insert my foot in my mouth in the process of provoking the kinds of responses that entail an interesting story.

DB (Laughing) It makes it lively though Charles.

CG Doesn’t it. (both laughing) It’s a lot of fun actually. I don’t want to come off as an Archie Bunker talking about the good old days.

DB You’re not. No. I’m not taking it that way.

CG I’ve reached a point of age where I am reversing the Abbie Hofmann dictum and now say “Don’t trust anyone Under thirty.” (both laughing)

And I really don’t. When I was a professor I often berated students for their social and political apathy. They seemed only interested in the inflated grades they expected and didn’t deserve. I was into my rant when there was a voice from the back of the room. “Oh Mr. Giuliano, you’re so Joan Baez.”

But it seems to be a fact of life that as we age and regard the work of emerging generations there are challenges of whether or not we want to engage. There becomes an ever wider divide and there is very little contemporary art, like this year’s Whitney Biennial, that is of interest to me. It doesn’t seem worth the effort when there are other demands upon my resources.

You’re absolutely right if I am apathetic and disconnected with a narrative from Glenn Ligon, an openly gay African American, or Amy Sillman relating thoughts on hanging out at bars with girls, well, they have the right to do that. I should be more respectful and receptive than I am.

DB Even though it’s not the Cedar Tavern I like the idea that people are still talking about painting over drinks. In a way the historical characters and situation couldn’t be more different but somehow the idea that paintings is still something worth fighting over and talking about. That, for me, was a good take away. And the fact that the audience was filled with young students who were thinking about what it is to make a painting.

A lot of the questions were very formal ones. The question “What about vantage point?” You’re 22-years-old and a painter and you’re thinking about vantage point! That’s terrific. That’s what you wanted to ask Byron Kim! You didn’t want to ask about the 1993 Whitney Biennial? It was the first time he showed Synecdoche which is an interesting story. But he wanted to know, right now, from an artist he seemed to respect, things about a very formal issue.

CG Picking up on that in Cooper’s essay the discussion of horizontality vs. verticality was interesting. How Pollock painted on the floor but then, as Rosalind Krauss pointed out, the viewpoint from creation to exhibition changes when the painting is hung on the wall. So we see it differently from how the painting was created. It becomes revelatory regarding how the viewer enters the pictorial space.

DB Yes.

CG That relates to Marden’s idea of cheap shots. How does the painter connect to the edges? How does Marden end a line? There are quick, easy and obvious ways to do that. (cheap shots) Byron Kim illustrated that issue when talking about difficultites in attempts to resolve the fields of his Night Sky series. To resolve the fields he surrounded them with thin framing edges which connect to the confining rectangle.

We come to a Clark seminar with an open mind and then encounter fresh ideas. It allows us to look at the familiar differently.