China's Yunnan Province: Part Two

Dali and Lijiang

By: Zeren Earls - Sep 11, 2016

After leaving Kunming, our group of nine headed northwest toward Dali, an ethnically rich autonomous prefecture of China, 250 miles away. Driving by green hills and tobacco fields dotted with women farmers, we stopped at a vineyard where organically grown grapes were being harvested. Then we continued on the Southern Silk Road, which is also called Burma Road, as the Burmese border is about 200 miles away.

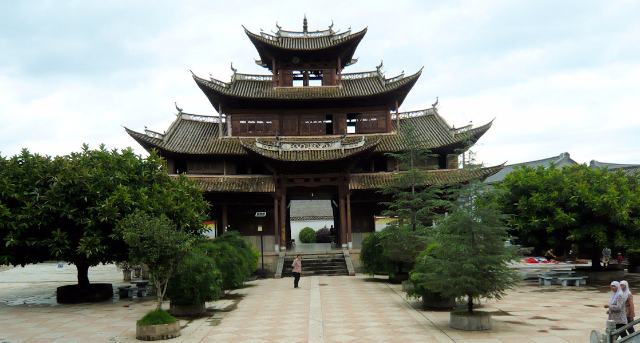

A stop in the small village of Yunnanni introduced us to the Bai community. We entered the village through a two-story high towering gate of wooden pillars, supporting multiple upturned eaves. The main street revealed the traditional cobblestone road construction, with a narrow strip in the center to accommodate horses’ hoofs and pedestrians on either side. Houses still had door decorations left over from the Chinese New Year celebration; these are believed to bring good luck to the home until new ones go up the following year.

One of our fellow travelers had brought a bag of reading glasses to distribute to the needy. She gave them to two women who were sitting on their doorstep, causing them to jump up with gratitude. As soon as the women put on the glasses, they broke into smiles – proof that their fuzzy world was now in sharp focus. This village has a warm spot for US visitors, as American forces helped the Chinese fight the Japanese from 1939 to 1945 by establishing a camouflaged US air base here. The Flying Tiger Museum is dedicated to their memorabilia.

The dominant ethnic minority in Dali is the Bai people, who are directly involved in governance. Daisy, our local Bai guide, was a delight to meet. She wore her embroidered white ethnic garb (bai means “white?) under a blue smock and a tasseled round hat made of four bands, each a symbol of nature – moon, flower, wind, and snow. A long tassel was indicative of her unmarried status, as opposed to a short one for married women. She led us to the Landscape Hotel in Dali, where we spent the next three nights. The hotel, near Dali’s walled Old Town, belonged to royalty 500 years ago. Similar to the houses in Old Town, it was centered around a courtyard, surrounded by flowers. We ended the long day with an evening stroll and dinner.

The next day’s excursion was to the morning market in the village of Xizhou. The market buzzed with activity as shoppers filled big baskets strapped to their backs with fresh produce – a daily ritual for Bai people. We then visited a traditional village house with a courtyard, marble decorations, and upturned eaves. Stopping on the street to taste pancakes cooked over a brazier was a further treat.

A horse cart with a colorful canopy provided us a quick tour of the town before we visited a Bai family for a home-hosted lunch. We enjoyed a variety of dishes served over rice in small bowls, such as fish with chili peppers, sprouted tofu, fresh peas in the pod with pork, shredded cabbage, fried pork rind, and zucchini. This feast was followed by a Three-Course Tea ceremony, which is offered to honored guests. By a charcoal fire our hosts, a middle-aged husband-and-wife team, gathered the items needed, such as clay and metal tea pots, a variety of tea leaves, and honey. As the husband fanned the fire, his wife stirred the leaves in the clay pot, to which hot water was added from a thermos. The process is repeated three times with different combinations of ingredients, each with its own symbolic meaning.

In the afternoon a boat ride on Lake Erhai took us to Jinsuo island (meaning “Golden Shuttle”), named after its shape, where all families make a living by fishing. Cormorant fishing is no longer allowed, as it required the cruel practice of tying a string around the neck of the bird to keep it from eating a big fish it had caught. On the island we visited a small 14th-century tiered-pagoda with multiple eaves, along with the Protector’s Temple, which is unique to each Bai village. The Buddhist temple, for all Chinese people, was guarded by dragons, as it is believed that they will bring on rain upon receiving prayers.

Our last tour of the day was back in the Old Town, where we visited the Catholic church, built by the French in 1932. In addition to the Bai, other minority groups were out and about, distinguished by their head cover – Yi people from the mountain region with their black hats, Hui Muslims with head scarves, and Tibetans with simple caps. As we walked by the high school, a big sign congratulated students on their 100% university acceptance rate. School lasts from 7:30 am until 5:30 pm with a one-hour lunch break. School study is required from 6:30 to 8:30 in the evening as well. Compulsory education is nine years following kindergarten. Learning English begins in third grade.

Dali is known for handicrafts such as batik, silver work, and marble. We visited a batik shop, where indigo plants were being grown in a small back yard. Here I purchased a shirt and a bag. On the way back we stood in front of a candy shop and watched an employee pull taffy. Then dipping it in sesame seeds, or in crushed peanuts and rosewater, before cutting it into pieces – a sweet ending to a full day.

On our last day in Dali we drove to Weishan Valley, where Yi, Bai, and Hui Muslim minority cultures co-exist. We began in East Lotus village, home to the Hui, at a mosque built in Chinese folk style and topped by a Muslim crescent and star. In the courtyard groups of women of various ages were preparing food for 400 people for iftar, the evening meal to break the daily fast, as it was the month of Ramadan. The mosque is open for prayer only to men; women pray at home. Allowed to look in the door, I could see a page from the Koran inscribed on the wall in Arabic, with Chinese inscriptions nearby.

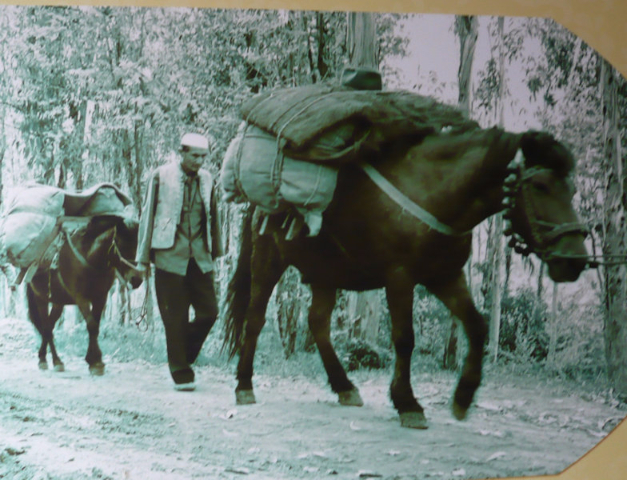

The next stop was a Hui caravanserai along the ancient tea and horse road. We visited the Horse Caravan Museum, which highlights the ancient tea trade in the region with old photographs, saddles, and utensils used at the time. A tour of the old town in Weishan, the first capital of Yunnan 1200 years ago, revealed charming old houses with upturned eaves facing surrounding mountains, as well as quaint shops with specialties such as fried jellied tofu chips.

We then drove to Weibao Mountain, which harbors two Tao temples. Climbing 200 steps, we arrived at Wenchang Palace, also known as Longtan Temple, which features a dragon at the entrance and was a place for worshipping dragons in days gone by. A statue of Emperor Wenchang (1314 AD) is worshipped as god of culture and literature in the main hall. The other temple offers protection for the Yi people. Taoism is a religious and philosophical tradition in China that emphasizes a way of life balancing the complementary powers of yin and yang. On the way back we drove by the new quarters of the city of Dali with its soaring high-rises.

Our last China adventure was in the northwestern city of Lijiang, nestled in the high mountain plains at 7500 ft. on the Silk Road to Tibet. We arrived in the village of Baisha, just outside of Lijiang, where the Naxi culture has thrived for 1400 years at the foot of Yulongxue (Jade Dragon Snow) Mountain, which is 18,000 ft. high. The Naxi people, who migrated here from northeastern Tibet, consider the mountain peak sacred and do not allow hiking. The 13 peaks of the impressive mountain, mantled with permanent snow, were shrouded under clouds at the time of our arrival.

Three rivers that originate in Tibet run parallel in Yunnan Province, forming the legendary paradise on earth, Shangri-La, in the northwest. Austrian-American botanist and explorer Joseph Rock (1884-1962) lived in the village of Yuhu near Lijiang from 1922 until 1949 and wrote several articles with pictures about this area for National Geographic magazine. His residence, a traditional building with upturned eaves around a courtyard, is now a museum, as Rock became famous and a leading authority on the Naxi culture and local flora. The museum has cultural relics and photographs in addition to Rock’s furniture.

A noteworthy natural phenomenon in Baisha is a 500-year-old, 8-meter-tall ornamental fernleaf hedge willow in the courtyard of Liuli Palace. Seeking light, the trunk of China’s oldest willow tree has split in two, fanning out majestically on either side to the north and the south, spanning the width of the old palace courtyard an amazing sight.

An ancient capital of the Naxi kingdom for 1400 years, Baisha is famed for its temple frescoes dating from the 15th and 16th centuries. The figures of the frescoes reflect the different traditions of Buddhism, Lamaism, Taoism, and the Naxi Dongba religion; their subject matter, painted in intense colors, is drawn from deities and daily life. The Dongba religion, named after its spiritual leaders, is based on nature worship, with concepts similar to those of pre-Buddhist Tibet. Dongba manuscripts were written in a pictographic script invented and read by Dongba priests.

Nearby is the Baisha Naxi Embroidery Institute. Founded in 818 AD during the Tang Dynasty, it was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution in 1972 but rebuilt and reopened in 2011 to sustain the living Naxi tradition of hand-embroidered silk. The institute operates under eight masters and 16 teachers; mastery requires ten years. Observing women at individual work stations embroidering meticulously with needles and silk thread inspired me to buy a small piece for framing.

Accompanied by our local guide, Kelsey, we then arrived at the Hexi Hotel to spend the first of our two nights in Lijiang. Lijiang is a town of 1.1 million people, 320,000 of which are Naxi, known for physical labor done by women. This became evident in the morning as we saw women at construction sites on our way to the market, where butcher stalls were also run mostly by women. In addition, they sold the usual variety of produce and eggs and did on-the-spot alterations on sewing machines.

The Naxi part of Lijiang is the well-preserved Old Town of Dayan. It retains its original layout and architectural style despite a major earthquake in 1996, following which it became a UNESCO Cultural Heritage Site. Houses along narrow cobblestone streets, crisscrossed by twisting lanes and canals, are built in tongue-and-groove style with no nails. Most of the buildings are now inexpensive guesthouses and shops. There is an entrance fee of 80 yuan (about $12) to maintain the area, which has no protective walls.

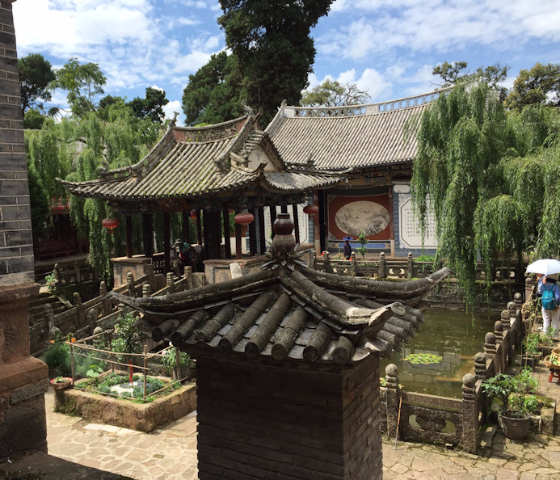

Just north of the Old Town is Heilong Tan (Black Dragon Pool) Park, a wonderland of temples, bridges, and water that reflects its lush surroundings. Jade Dragon Snow Mountain is discernible from here between an arched marble bridge and a three-story Chinese pavilion. Within the park is also the Dongba Research Institute and a museum, where pictorial manuscripts, clothing worn by shamans, and artifacts found in excavations around the area are on display.

A Naxi hot pot for lunch introduced us to yet another tradition. We cooked our own food from a selection of various fish, sausages, tofu, Chinese cabbage, taro noodles, and potatoes in a pot of hot broth over a burner in the middle of the table. Served over a bowl of rice, this meal was accompanied by side dishes of pickled cabbage, eggplant, and squash — a tasty meal indeed.

A local shaman in his 60s named He Ziqian visited us at the hotel to provide further insight into Naxi customs and beliefs. Wearing a traditional costume and hat with five peaks representing gods, the center one being the founder of the religion, he shared with us the creation story of the Naxi People. A man climbing out of water marries a woman, who appears with a lightning bolt in the sky. From this union three boys are born, each becoming an ancestor of Naxi, Tibetan, and Bai people. Thus the Naxi worship of nature was born. Shamanism is passed on from father to son, Mr. He being the 14th generation title holder. To become a shaman takes many years of training, including the learning of 28 types of dance. This informative meeting ended with Mr. He’s performance of the frog dance with his cheeks puffed up as he moved.

The following day we flew back from Lijiang to Kunming to continue our itinerary to Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia via Beijing. I had found the week spent in Yunnan Province a most engaging trip. The only downside was the fact that Google is banned in China and I was unable to use my Gmail address – just like the days before the world was so vastly connected electronically.