Joe Manning on The Lewis Hine Project

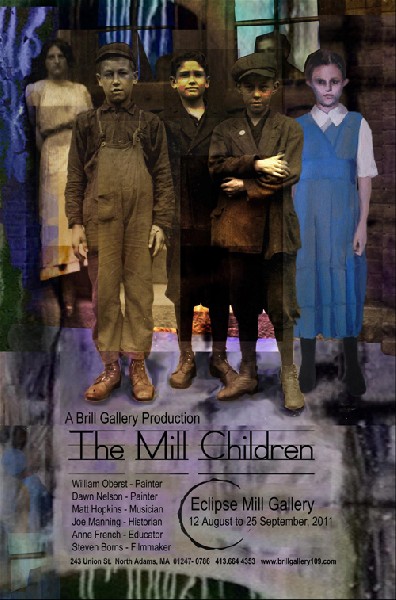

The Mill Children at the Eclipse Mill Gallery

By: Joe Manning and Charles Giuliano - Sep 12, 2011

Charles Giuliano This summer Ralph Brill organized a project and exhibition The Mill Children for the gallery of the Eclipse Mill. It was inspired by the fact that Lewis Hine photographed children who worked in the Eclipse as well as other mills in the region.

What has been your part of the project? How did you become involved with this research?

Joe Manning In the North Adams area, Hine took photos at one mill each in North Adams, Adams, and Pownal, VT, but none at any other mill in the area.

I provided the results of my research about the lives of some of the boys that Hine photographed at the Eclipse Mill. I also functioned as a consultant about Lewis Hine's work, the working conditions at the Eclipse Mill, the primarily French Canadian culture of the neighborhood around the mill, and the lives of typical working-class families in the area at that time. Currently, I am making presentations about the exhibit, and about Hine, to teachers and students, most recently addressing a group as if I were Lewis Hine at the end of the day that he took the Eclipse photos.

My research, called officially the Lewis Hine Project, stemmed from being asked by author Elizabeth Winthrop, a friend, to track down the life of Addie Card, a mill worker who was photographed by Hine in Pownal, Vermont. She had written a novel for children about Addie, but since the book was historical fiction, she had called the girl Grace, and the book, "Counting on Grace." When the book was completed (2005), Elizabeth was curious about what the real Addie Card was like, and what happened to her. I found out, which resulted in Elizabeth and I doing an interview with some of Addie's descendants, none of whom knew about the Hine photo. I enjoyed the experience so much, that I decided to try other child laborers the Hine had photographed. In the past six years, I have tracked down the lives of over 250 child laborers, from over 20 states.

CG There is the notion of The Concerned Photographer. In the early 20th century that begins with Jacob Riis (1849-1914) and Lewis Hine (1874-1940). They were activists as well as artists using the camera to document and arouse viewers to issues of social injustice in America.

How were their images seen by the public? Where they photographing for publications? Were they leftist/ liberal media that preached to the choir? Did their images reach a main stream of the American public? Today we look at the images of child labor and it seems a given that it would result in legislation. But how did that process work during their time and generation?

Of course it is fascinating that Riis and Hine were precursors to the many American photographers from Margaret Bourke White, Dorothea Lange, to Walker Evans who recorded the suffering of the Great Depression. Many photographers worked for The Department of Agriculture and its Farm Security Administration (FSA). Their negatives are archived by the Library of Congress. Was that the case with the Hine images that were used for the Eclipse exhibition?

JM I have not yet looked much at the work of Riis, but I do know that his book, “How the Other Half Lives,” caused a sensation, and was attributed as one of the reasons why New York City passed stricter laws regulating public health and safety standards for tenement housing.

Hine’s photographs were widely circulated in magazines, newspapers and journals by the National Child Labor Committee, his employer. The Progressives would have been very much aware of them, the educated general public somewhat less aware, and the rest of the general public mostly unaware. But mill owners and politicians would have taken notice right away. Although there were many organizations and activists working to get child labor laws passed at the time, Hine’s photographs are generally recognized as the most important reason why states began to strengthen child labor laws, and why Congress passed the Owen-Keating Child Labor Act in 1916. Unfortunately, the law was ruled unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court in 1918, because it appeared to overstep the authority of Congress in regulating interstate commerce.

All of Hine’s child labor photographs, and captions, including the ones at the Eclipse Mill, are in the Library of Congress and are posted on its website. In addition, an extensive collection of the photos, negatives and captions are owned by the George Eastman House in Rochester, NY, and the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. The collection at the Library of Congress has no copyright limitations.

CG Do you know when and why Hine decided to photograph in the Eclipse Mill? How long did he spend photographing? Were there issues of his gaining access from management?

JM The National Child Labor Committee directed Hine’s itinerary. Just before he was in North Adams, in late August 1911, he had spent a week photographing young sardine cannery workers in Eastport, Maine. After his visit to the Eclipse Mill, which probably was only one day, he went to Adams and photographed at the Berkshire Mills. Then he spent the next five months taking pictures at mills in Massachusetts, mostly east of Worcester. At the time, Massachusetts had the most progressive child labor law in the country, and Hine would have been checking to see if the law was being enforced.

Although he often gained access to the mills, he apparently did not in North Adams. Most likely, the owners got a tip about it and confronted him.

CG Can you discuss the children who worked in the Eclipse Mill? What were their ages and ethnic backgrounds? The area is known for its Polish, French Canadian and Irish communities. Were these the workers at that time? What did the Eclipse Mill produce? What were the working conditions as well as length of the work day? We would assume that the conditions were dangerous and unsanitary. Can you give us some detail?

JM In the nine photos that he took at the Eclipse Mill, Hine identified six of the children: Albert Duquette, Joseph Crepeau, Joseph Allard, Josephat Adams, Arthur Chalifoux and Richard Fitzgerald. The first five were French Canadian, which was the dominant nationality of the residents of the neighborhood around the mill at that time. There were very few Polish immigrants in North Adams. Most lived in Adams and Cheshire. The six identified boys were between 13 and 15, except for Josephat Adams, who was 10. Most would have started working when they were 10 or 11, and would have quit school to work full time by the sixth grade.

The Eclipse Mill was essentially a cotton mill. It processed cotton that was shipped from the South on trains. The mill was populated by noisy spinning machines, and workers were likely to incur gradual hearing loss as a result. The air was filled with cotton lint, which caused many to have respiratory problems. Since children are naturally careless and easily distracted, the fast-moving machines posed a great danger for them, often leading to injuries, some of them serious. But since record keeping was poor in those days, and there were few occupational safety standards, we have no clear evidence of how many accidents there were. Children who worked full time probably worked as many as 12 hours a day, six days a week.

All the six boys I researched lived to adulthood, and none appeared to have died directly from a work-related illness. Crepeau, Adams and Chalifoux survived into their eighties and nineties. Duquette became a prize fighter, and died suddenly at the age of 39.

CG By what process were you able to research the children whom Hine photographed both at the Eclipse and other sites? I understand that you have been involved for six years in this project. What has been the primary motive for taking this on? What has been the result of the research? Where does it currently stand and are there plans for its continuation?

JM The research process is similar to genealogy research. I use a combination of Internet resources such as the US Census, paper archives in city and town halls, and newspaper archives. The difference in my research is that I am tracking forward for descendants, not backward for ancestors. For those children that Hine has named in his captions, I use a variety of government records to establish their correct names and years of birth, and then try to find out when and where they died, which then allows me to locate their obituaries and a list of their survivors. Then I search for the survivors and interview those I find. If the child is a girl, it is a more difficult task, since most die with a married name that I don’t know at the outset. In those cases where I am unable to find out the married name, I search instead for descendants of a male sibling.

In a few cases, I have identified children that Hine did not name by persuading the newspaper in the town they were photographed to publish the photo, in the hope that a reader will recognize the child. I have been successful with that strategy nearly 10 times.

My approach to history has always been biased toward the unrecognized classes, instead of the privileged classes that dominate history books. I am motivated by the need to dignify the lives of so-called ordinary Americans, and this is a good way to do that. So far, I have tracked down the stories of over 250 child laborers.

But I discovered early in my project that the most significant result of my work is revealing the Hine photos to descendants who had no idea they existed. That has happened in nearly every case. For many, it is the first time they have seen a picture of their parent or grandparent as a child. The joy of doing this is what drives me to continue the project, and I plan to do it for many more years.

CG There are educational programs being developed out of the Eclipse Mill exhibition. During a presentation to school administrators you assumed the role and persona of Hine. What are the plans from here? Talking with Ralph Brill, who organized the project, he related that the exhibition will travel to Bates College in Maine and other venues. It appears that a number of communities with mills and a history of child labor are interested in having the exhibition.

The project has resonated with individuals and its connection to their family histories. It reaches beyond the perception of the usual gallery or museum exhibition. It combines both the aesthetic of visual art and historic photography as well as a component that connects with audiences in a very real way.

Many of the mill buildings have been renovated to serve very different functions than were originally intended. At times that results in a kind of disconnection between the current owners/ occupiers and members of the community who have a different relationship with those historic structures.

Mass MoCA, for example, is now an enormous museum for contemporary art in what was formerly Sprague Electric Company. In a changed economy many of these factories have been abandoned and are in varying states of disrepair. Reconfiguring Sprague as an art museum, or the Eclipse as an artist loft building, has saved threatened structures. Not only have the buildings been preserved but they also have contributed to the economy of financially downtrodden communities.

Local citizens going back for generations, however, tend to take a different and at times resentful view of these changes. Some hold out hope that the kind of fabrication produced in the mills will return. The mills linger as signifiers of jobs and a now lost way of life. Those with roots in the community, including artists who grew up here, talk about the vitality of mill towns like, Pittsfield, North Adams and Adams back in the day. They recall when Sprague had three shifts and the streets were busy with shops, movie theatres, bars, restaurants and a bustle of activity.

If you read the comments in local papers like the North Adams Transcript there are flash points of resentment. The change to a creative economy has come with transition and some resentment. That was evident in the divisive run for mayor that saw the ousting of John Barrett after decades in office and Dick Alcombright who was successful in rallying a coalition of long term residents and newcomers.

It is particularly relevant that Brill and the Eclipse Gallery are the impetus behind a telling of a history of the mill and the struggle to end child labor in America. Until this project it was something that most of us were only vaguely aware of. As an owner and resident of an Eclipse loft unit it makes me respond to and think differently about the space.

What is the value of telling this story? In what way is this more than an exhibition, or in your case, a research and book project? Are there as yet untapped ways to bring more local people and artists into a meaningful dialogue around these talking points and works of art?

JM Your comments and questions regarding the community’s adjustment to moving from a manufacturing economy to a city known for art and tourism deserve a long and thoughtful answer. I have discussions with people about the subject all the time, and I have my own strong opinions about it. But I will try to be brief.

In order for the city to benefit fully from the influx of artists and other creative people, those newcomers must be mainstreamed into the community. That means that they must send their children to the local schools, use the public library, vote in local elections, run for political office, and attend Steeplecats games, high school football games, church suppers and fundraising events. In short, they need to melt into the community.

The city has always changed in every generation, much more radically than we perceive at the time, and it won’t survive without changing again, and without new residents who have new ideas. Fortunately, for the most part, the people moving here now are making a quality-of-life decision, not just an economic one. So they are more likely to want to preserve the things they like about the area. I’ve heard many comments from these new people about the beauty of the area, the many opportunities for outdoor recreation, and how friendly the locals are. This is a good sign.

Regarding your question: What is the value of telling this story? In what way is this more than an exhibition, or in your case, a research and book project? Are there as yet untapped ways to bring more local people and artists into a meaningful dialogue around these talking points and works of art?

The value of this story in North Adams is the exposure of our vernacular history to new people, instead of its formal and academic history. And the value to the people who have been here for generations is the recognition of the contributions that their ancestors have made to the city, and the broader meanings of that contribution. Finally, it’s a way to connect the past with the present inside the buildings that reflect the city’s working class culture.

THE MILL CHILDREN Exhibition has been a year long collaboration between myself, Realist Painter William Oberst, Abstract Painter Dawn Nelson, Historian Joe Manning, Composer/Musician Matt Hopkins, Filmmaker Steven Borns and Educator Anne French. Anne has produced a Teacher’s Guide. See Website for Info. The Exhibition at the Eclipse Mill Gallery has been extended to 8 October 2011. This Winter this Exhibition will be at the Williams College Campus. We are in discussions with the Gallery at the Lowell Mills and the Mills Museum in Lewiston, Maine for Spring and Summer 2012 Exhibitions. Other Mill Museums in Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Connecticut are being planned. A BRILL GALLERY PRODUCTION – Ralph Brill

The link to Joe Manning's Lewis Hine Project web pages is:

www.morningsonmaplestreet.com/lewishine.html