Susan Erony: Scribe as Artist

Transcribing Text Into Images

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 13, 2016

During our recent week at the Gloucester Writers Center we were immersed in the conundrum of poet Charles Olson (27 December 1910 - 10 January 1970).

To prepare for the artist’s residency, in April, I started reading his “The Maximus Poems.” It is difficult and slow work. Now in early September I have reached page 491 of 635. While in Gloucester, to get the full impact of Olson, I read intently.

With a lifetime syndrome of ADD I am an eclectic but distracted reader.

It has been interesting to discuss how others deal with Olson. Even individuals with direct and significant involvement convey that they consult and sample Maximus rather than actually read it straight through. Like The Bible.

It is impressive how Televangelists punctuate every thought with a quote from scripture. Even Presidents have been know to do this since, other than Kennedy, all have been Protestants.

It would be more impressive if priests and politicians colored their remarks with quotes from Maximus. It is the least we can expect from Gloucester’s poets and pundits.

Or artists.

I was astonished to learn that our friend Susan Erony made a complete copy of Maximus. She has displayed it as a work of art.

Text has long been an important element of her work. There have been projects entailing Kafka, other writers, as well as a task of reading and disassembling Bibles as collage materials.

Currently she is completing work for an exhibition "Susan Erony: Towers and Other Thoughts" for Gloucester's Trident Gallery, October 29 to November 27, 2016.

Her daunting project to transcribe the massive Maximus prompted an overview of the role and legacy of the scribe in our culture both ancient and contemporary. In the process of recording every word of text is a scribe a technician or a scholar and seer? Does that intimate connection equate to a deeper understanding than reading the same text?

Prehistoric describes people and cultures that are illiterate. That can be both ancient, mankind as hunters and gatherers, or entail remote tribes in the Amazon or Indonesia with little or no contact with the outside world.

With the development of language, symbols and signs into sophisticated texts and systems of writing it entailed both the pragmatic as well as visionary.

The Old Kingdom Egyptian polychromed, limestone sculpture, “Seated Scribe” depicts a man of noble bearing, wisdom and status. He represents one of the relatively few literate individuals in that hierarchical culture.

The tasks that he performed, creating documents and transcribing religious, social and political texts, were essential to the function of a dynamic and sophisticated society.

From ancient times, until Martin Luther’s vulgate Bible printed by Guttenberg, the written word was the realm of a small segment of society. In general, it was the domain of priests and clerics charged with knowing and disseminating sacred texts.

The first universities clustered around monestaries with their critical mass of handwritten books and manuscripts.

Even the Holy Roman Emperor, Charlemagne, never managed to read and write. Einhard ( c. 775 – March 14, 840 AD) in his Life of Charlemagne tells us that he kept a slate next his bedside and practiced but never mastered letters. Yet he spoke several languages and scholars were prominent in his court.

As a Catholic educated by nuns we read Catechism but not the Bible. That was given to us at mass and interpreted in sermons. Because of illiteracy and fear of misappropriation, from the middle ages through the Baroque, scripture was depicted on the walls of churches and in their sculptural elements.

The Inquisition punished artists who deviated in their interpretations of sacred texts.

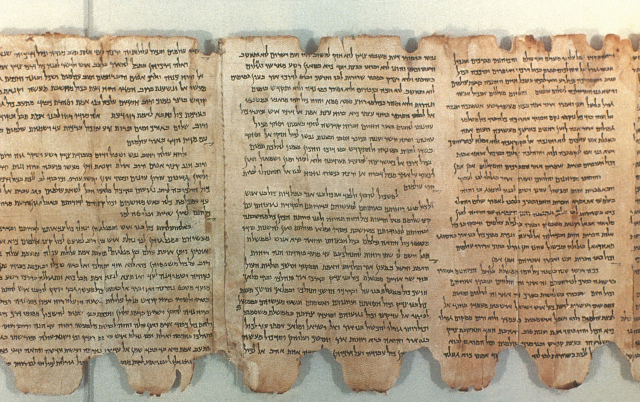

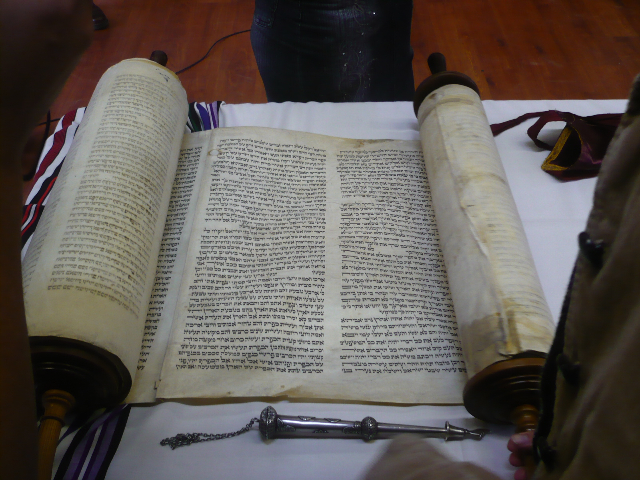

From ancient times, to modern day calligraphers creating Torah scrolls for temples, the scribe has been uniquely gifted and important to sustaining The Word both ancient as well as contemporary.

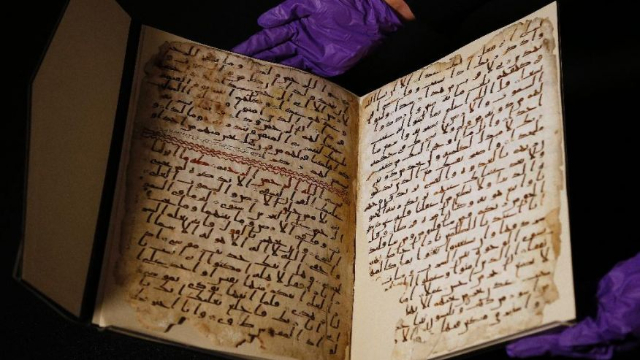

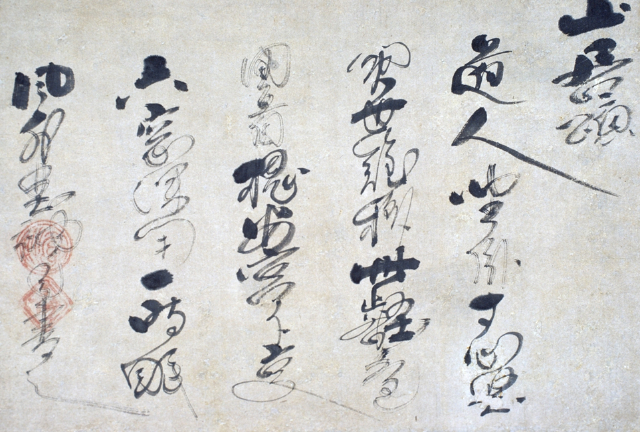

In Islamic and Jewish cultures, because of the ban against the Graven Image, the beauty of calligraphy has particular importance. This is also true for comprehending Asiatic art and the significance of calligraphy. These are aspects of aesthetics that are all but lost on our culture with its emphasis on the printed word. We focus on the meaning of words and not on how they are rendered.

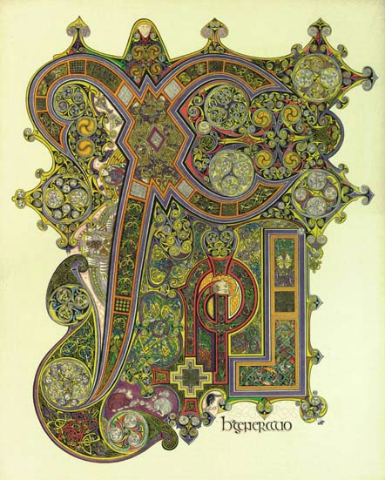

Transcribing is labor intensive work for which there is humble compensation. Arguably, the Carolingian scribes of Ireland, the monks that produced the handful of texts like the iconic Book of Kells, labored for their daily bread. A major part of their compensation was the love of God and work in His name.

Arguably, the undoing of the unique status of scribes starts with Guttenberg and is further exacerbated today by all forms of media from TV to texting. Respect for word and text has devolved into millennial semiotics.

After decades of using keyboards my handwriting has been reduced to a scrawl. A hasty blur passes for my signature on checks and documents. Long gone is the Palmer Method taught to me by nuns.

While The Seated Scribe was prominent in the royal court today his job description would be secretary or bean counter. The once unique skill set is now so common that it earns little or no respect.

The ancient scribe’s sacred and unique functionality has morphed into the flying thumbs of teens embracing their smart phones and texting urgent but vacuous thoughts to their mates. It is a moat that separates them from my generation. Many of us grew up loving and surrounded by books.

I wanted to know more about Erony’s aesthetic, obsessive- compulsive use of text. We discussed this by phone. I was interested in the mechanics like how many hours a day and the duration of the projects. Somewhere in the midst of it she broke her wrist and that impacted progress.

She described how transcribing Olson was a means of forcing herself to read him. There had been several prior abandoned attempts. In hindsight she revealed that it would have been better to read the text, any text, before transcribing.

When undertaken in the name of religion one may understand such efforts as divine madness. How then to explain and justify such an all-consuming approach to a profane text? Perhaps there is something sacred about Maximus and why it is so formidable and daunting to approach let alone comprehend.

While not religious or Biblical it is arguable that Maximus is epic, Homeric, in its ambition, scope, historicism, and poetic confluence of fact and fiction in poetic form.

Erony sent me notes starting with the Kafka project.

But Take Another Abraham

1994

Acrylic and pencil on canvas, suspended from lead strip

87 x 78 inches

These words are taken from Kafka’s parable, On Abraham:

"But take another Abraham. One who wanted to perform the sacrifice altogether in the right way and had a correct sense in general of the whole affair, but could not believe that he was the one meant, he, an ugly old man, and the dirty youngster that was his child. True faith is not lacking to him, he has this faith; he would make the sacrifice in the right spirit if only he could believe he was the one meant. He is afraid that after starting out as Abraham with his son he would change on the way into Don Quixote. The world would have been outraged at Abraham could it have beheld him at the time, but this one is afraid that the world would laugh itself to death at the sight of him. However, it is not the ridiculousness as such that he is afraid of – though he is, of course, afraid of that too and, above all, of his joining in the laughter – but in the main he is afraid that this ridiculousness will make him even older and uglier, his son even dirtier, even more unworthy of being really called. An Abraham who should come unsummoned! It is as if, at the end of the year, when the best student was solemnly about to receive a prize, the worst student rose in the expectant stillness and came forward from his dirty desk in the last row because he had made a mistake of hearing, and the whole class burst out laughing. And perhaps he had made no mistake at all, his name really was called, it having been the teacher’s intention to make the rewarding of the best student at the same time a punishment for the worst one.”

Representation for a Ritual of Unease

2001-2004

Paper, charcoal, pastel, acrylic, oil on canvas

66 x 42 inches

Collection New England Biolabs

In my concern with the ill use of religion to fuel the fires of hatred, I assigned myself the task of reading the entire Bible in the summer of 2000. I bought two worn and damaged copies of the King James Bible, and, as I read each page, tore it out and glued it down to the canvas, covering the surface. As I finished each layer, I covered it with a layer of burnt paper. When I finished the first Bible, I used the second to build a tower of both hope and despair. I then worked the surface with paint, pastel, photographic negatives and found objects.

In doing this piece, I was searching for a way to understand the power of the Bible in western society, the way in which it has been used to support so many human actions, motivations and desires. Its different interpretations have led to horrible events, and yet it is a moral guide for many. I was trying to come to terms with the complexities of faith.

The tower is, in part, a Tower of Babel, in part a monument to distress, in part a ritual mound for mourning. The piece is a container for my thoughts and emotions about the use and misuse of Biblical words. The Bible is a document whose power in the West is remarkable, whose potential for application to the very best and the very worst of human desire has been manifested over and over throughout its existence.

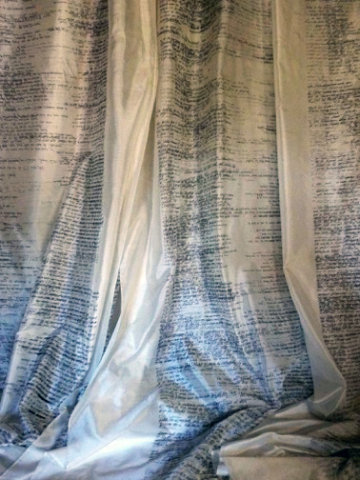

To Gloucester, with Love

2008-2010

Permanent marker on silk

69 x 3.75 feet

I moved to Gloucester in 1995 for four months. I am still there and still trying to understand why I fell for it so and why it is the only place I have ever felt at home. I decided to read Charles Olson’s epic poem focusing on Gloucester, the Maximus Poems, and to transcribe it, immersing myself in it physically as well as visually and intellectually. I hoped his homage to the city might help me understand. That transcription is To Gloucester with Love.

Hand copying is a process I had used extensively with Kafka’s writings. Transcribing turns words and the letters they contain into purely visual forms carrying a mystery within them. I find text beautiful as image, and writing by hand a means of research.

After the two years I spent transcribing the Maximus Poems, I did not and still don’t know why Gloucester has such magic for me, but I gained a deep sense of yet another artist’s obsession with the land and sea Gloucester encompasses. To Gloucester with Love is my ode to Olson and his passion, and to Gloucester through him. He said so well what we have, have already lost, and still can lose in this wonderful city, in the greater world, and in our own lives. He spoke of the local and addressed the universal. I have respect and awe for Olson’s momentous work, and this piece is my attempt to communicate the depth and profundity of his great work of art.