Rethinking African Art and Culture

Discussing Content and Impact of a CAA Panel

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 13, 2025

Some time ago Noah Smalls sent to me a transcription of the academic panel “Toward an Inclusive Framework: (Re)Building Black Art Histories in Academe, the Art Market, and Beyond,” presented at the 2025 College Art Association Conference.

I read it initially and then again a couple of days before meeting him for lunch to discuss it. My Haitian friend Robert Henriquez joined us at the Williams Faculty Club. As an 84-year-old art historian, artist, critic and curator that provided a lively and insightful triangulation to engage in a challenging discussion of emerging views and approaches to the repatriation, research and presentation of the “belongings” of traditional African art.

The intensive reading and critical discussion called into question some of my responses as one with the background of traditional art history through the lens of white privilege.

An example would be concerns I expressed for the preservation of objects returned to African institutions that may lack conservation standards properly to conserve them. Noah sharply rebuked and exposed that and other seemingly benign positions.

There is a learning curve for myself as well as for others in the fields of art history, criticism and museology. The CAA transcript and our discussion of it comprised radically new paradigms and strategies intended to activate and explore the hidden dialogues that the objects represent. It was discussed that many objects have yet to be named and identified.

To do that detective work Noah described a discourse across a number of disciplines including history, art history, anthropology, dance, music and economics. Of primal concern is having people of the culture in question participating in the discussion. What is their collective memory and DNA related to the object? If it was not created as an art object what was its original function in ritual?

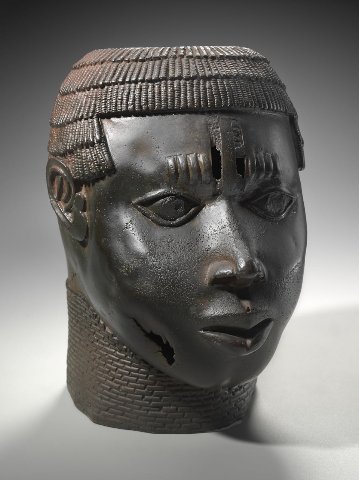

That context is entirely missing when the object is displayed in a vitrine with museum level lighting and inadequate labels. This has become ever more acute as objects have moved from ethnographic to fine arts displays. What happened over the past generation when key examples found their way into “encyclopedic” museum collections? Visitors were encouraged to view Benin bronzes and African masks on a level playing field with examples of global art. There was a false assumption that the techniques of classical art and art history are adequate to approach an appreciation and understanding of objects of belonging.

The CAA panel trounced those false narratives. A formalist approach is adequate to evaluate some but not all aspects of pieces that were not intended simply for aesthetic pleasure. That may work in part for a Benin bronze but not at all for unidentified artifacts disconnected from their original function. Noah explained that there are thousands of objects in European collections that are unlabeled and so poorly narrated that they are never displayed. Objects continue to be presented in a Colonial context having been looted and ripped out of their indigenous practice.

In the context of Colonialism everything in sight was looted and taken back to the museums of that nation. In this manner the collections reflect the African nation that was under European rule. Significantly, tons of Benin bronzes have been returned by German museums. By comparison several works that were promised gifts to the Museum of Fine Arts have been returned to the collector.

The MFA has closed its Benin Kingdom Gallery, but most of the works it had been created to display will not be repatriated to their place of origin. Instead, all but five of the objects will be returned to their donor, the filmmaker and banking heir Robert Owen Lehman.

Some of the objects in Lehman's collection were stolen during a 1897 raid on Benin City in present-day Nigeria, during which British troops sacked the African empire's royal compound and took thousands of artefacts.

In recent years, the Nigerian government has called upon institutions to return Benin Bronzes, but because the MFA Boston does not own the Bronzes outright it was unable to unilaterally do so.

Meetings, between the MFA and Lehman came to a standstill. The museum negotiated for Lehman to transfer title of the objects in exchange for a long-term loan, instead, the donor asked for return of the artefacts.

The MFA's former director Matthew Teitelbaum described a “mutual agreement,” in which Lehman rescinded the gift.

Lehman originally donated the group of 34 pieces in 2008 in a deal brokered with the MFA's then-director Malcolm Rogers. The gift was structured on a staggered timetable, so that individual bronzes would enter the museum’s collection over time. Teitelbaum stated that the museum “paused” the Lehmann gift in 2021. As of today, the MFA holds titles to five of the objects in the Lehman gift, and those artefacts will remain in the MFA’s collection. The museum now displays the five remaining Benin Bronzes it did acquire from Lehman's collection in its Art of Africa Gallery.

As an anecdote Noah described one such gallery in an Italian museum. In good faith the curator invited a delegation of Africans to view the installation. There was shock and lamentation when they experienced the display. The curator was asked to leave while the individuals discussed their responses and actions that the museum should initiate.

He described experiences of visiting a European exhibition that conflated Pippi Longstockings and African objects. When he entered the gallery displaying the African objects there was no lighting. The curator explained that “It was a dark period.”

Henriquez discussed his experiences of interacting with an Australian collector/ dealer. When he managed to purchase an object, as he left the village, he was followed by a community mourning the loss of a work sacred to their culture. They later asked for it back and it was returned. Several years later there was change in the village’s leadership and the piece was again sold to the collector. Henriquez viewed it in the collection with other objects.

He explained that these pieces were not meant to last forever. When they are replaced the original object is taken back to the jungle and subject to the forces of nature. There is a ritual by which the maker chooses a tree to be felled. It is then enclosed in a hut to be carved by the maker and assistants. There is limited access of who may visit and view the process which might take several months. There are other rituals when it is taken to and installed in the village. In that regard the entire community is involved in its creation as well as mourning its loss.

Some 90 % of traditional African material comprises the colonial era collections of major European museums. The CAA panel addressed the moral and pragmatic imperatives of rectifying that inequity. How does a teaching museum like Williams College, in an ethical manner, integrate stewardship as a part of its educational mandate?

It was significant that the panel included private collectors committed to acquiring a critical mass of material while exerting due diligence regarding provenance, transparency, research, publication and loans to exhibitions. What happens when objects from the art market disappear and are no longer accessible to scholars?

This is follow-up to the panel and our discussion of it that Noah requested. While I have had the opportunity to engage with this emerging dialogue, that’s not true for the art world or general public.

It is up to the panelists as individuals and representatives of institutions to disseminate this information. While the CAA transcript represents initial discussion is there a way to clarify and condense it to a press release and bullet points? Would it be possible to generate 2,000 word articles and related images that might be posted to media?

The intent would be to refine radical new ideas and approaches that reshape the academic and museum field and ultimately create an approach to the general public.

There is discussion of organizing a traveling exhibition informed by these evolving concepts for installation and education. With appropriate labeling, audio-visual aspects, and a scholarly catalogue it would potentially provide a paradigm and template for museums. Repatriation is just an initial phase of a complex process.