Vietnam Part Two

Mekong Delta

By: Zeren Earls - Sep 14, 2010

The Mekong’s Vietnamese name, Cuu Long, means “Nine Dragons,” as the river descending from its source high in the Tibetan plateau forms nine branches before it finally empties into the South China Sea. The vast delta, known as Viet Nam’s rice bowl, is shaped by the alluvial deposits of the multiple arms and tributaries of the river. The heavily populated fertile delta is connected by a network of waterways and irrigation canals. Here the dry season lasts from November to April, while the rainy season makes up the rest of the year.

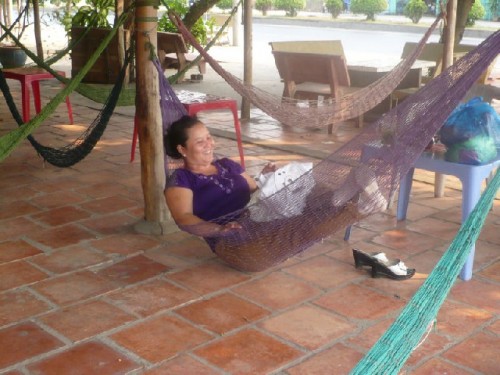

Traveling southward from Ho Chi Minh City on a super-highway, we drove by slash-and-burn farmland, sugar cane plants, coconut palms and banana trees. Rice fields stretched as far as the eye could see, creating a many-hued and textured patchwork punctuated with elaborate ancestral tombs. Ducks waddled in canals by farm houses decorated with flower pots in balconies. With intermittent views of water, we passed pedestrians in conical hats, children playing in a school yard, modern gas stations, and roadside cafes with hammocks for weary travelers. A mobile clothing vendor pulled his cart; motorbikes carried big loads, while high school girls in uniform long white dresses, symbolizing virginity, pedaled to school.

At a roadside stand we admired tropical fruits and discovered a specialty: fermented pork skin, made by boiling and mixing the skin with papaya and chili peppers and keeping it wrapped in banana leaves for three days. While I was not tempted to buy this specialty, I purchased peanut brittle on rice cakes and boiled peanuts in the shell, both of which made tasty snacks for the road.

Driving on a toll road, we crossed the Delta’s first suspension bridge, built by Australians. The level of the water below was low, due to China’s control of the river at the northern end. Ocean water has been seeping into the rice fields, raising concern over diminishing fresh water.

During the bus ride our Vietnamese guide, Anh, explained the country’s single-party political system. The Parliament has five hundred members; elections are every four years, at which time people vote for three out of five candidates from their area. The Parliament elects the President and the Prime Minister, who administers the five-year plan drawn up by the seven-person Political Bureau, the highest authority. The nation’s literacy rate is 90%; education on Communism begins in 9th grade. There is no social security or pension system. Everyone is expected to work; those who cannot are taken care of by their families. Insurance is a fairly new concept; motorbike insurance, required by the government, costs $4 annually. Big companies, including Prudential, have begun investing in Viet Nam.

Reaching the boat landing to cross the Son Hau River to Can Tho, the capital of Can Tho Province, we took the ferry across a busy waterway. With a population of one million, Can Tho is the Delta’s largest city and an important river port and commercial center. We missed seeing the floating market, where locals shop for a variety of fish, fruit and vegetables by crossing from boat to boat. However, the animated Can Tho market was quite rewarding with its several restaurants on the waterfront serving specialties of the region. Here we enjoyed lunch consisting of squash flower tempura, shrimp with mangoes and deseeded chili peppers, pork with mushroom sauce, and green beans with sprouts.

A walk after lunch offered a snapshot of local life. Rice, harvested three times a year, dried on bamboo mats by the roadside as farmers raked through it to speed up the process. Narrow houses with colorful, ornate facades lined the streets; stilted houses with tin roofs stood by the water’s edge; and picturesque shacks crowded the canals. Drivers transported passengers in rickshaws pedaled up front, unlike the rear-pedaled ones we had ridden in Saigon.

The amazing encounter of the day was our visit to the Cao Dai religious sect’s surreal temple of wildly mixed styles, colors and designs from every Asian religion and culture. On the outside, a large eye symbolizing the religion guarded the temple entrance. The interior was a fantasyland with a blue, star-studded, vaulted ceiling and dragon-entwined pillars. The eye symbol formed the centerpiece of an ornate altar embellished with candles, flowers and fruit behind a drawn curtain framed by a blue neon light. The light reflected on the shimmering green floor tiles, divided by neat rows of bright blue cushions for seats during service.

Founded in 1926, the Cao Dai religion is an amalgamation of religions preceding it. Adherents believe in one deity, practice meditation and are vegetarians. Their God does not appear in human form; instead, they worship a single left eye, known as “Ying.” There are four services a day, one every six hours, starting at 6 am. One percent of the population, predominantly in South Viet Nam, belongs to the Cao Dai sect.

On the way back to the bus, we noticed young children looking out at us from behind the bars of a first-floor apartment. Going around the corner to meet them, we realized that this was a preschool in one room. The teacher asked the children to sing for us as we crowded at the doorstep. This impromptu stop delighted us all.

As we traveled to Chau Doc to spend our final night in Viet Nam, Anh spoke about his family. At the end of the war in 1975, his father, a member of the “educated elite,” was sent to reeducation camp by the Communist regime. The government took possession of everything the family owned and forced them to work as farmers, during which time they could have meat once a month. In 1982 they were allowed to return to the city and had to begin anew by starting a home business renting clothes for weddings. Since people were too poor to buy wedding clothes, the rental business grew quickly. Following the death of Anh’s father in 1986, the business expanded into a full-fledged wedding operation, with each family member acquiring a specialty: flower arrangements, hair styling etc. It took them three years to fully recover from poverty.

Chau Doc is a city of 100,000 bordering Cambodia, and as such a melting pot of cultures with ethnic Khmer, Cham, Viet and Han Chinese people. After settling in our multi-story hotel, we toured the city by bicycle rickshaw on our way to dinner with a local family. Our hosts, a family of three generations, lived in a house with a storefront, where they baked and sold moon cakes (consumed during the traditional mid-autumn Moon Festival). The grandmother, her tired feet soaking in a basin of hot water, minded the eight-month-old granddaughter in her lap, while the mother served us a delicious meal: spring rolls, taro soup, lotus stems, catfish, fried noodles with shrimp, and squid. For dessert we had delectable sliced mangoes.

Visiting with this family reminded me of the time when a Vietnamese-American floor-sander had arrived at my house in Cambridge. Upon entering my three-bedroom house, modest by American standards, he had asked how many people lived there. My answer of “three” had astonished him; “Only three people in this big house!” he had exclaimed. Years later it became clear why.

Chau Doc is known for its “floating villages.” In the morning we visited one such village by boat. We cruised by the river banks, stacked with houses on stilts, and ambled through narrow canals lined with tropical plants. We steered by houses built on empty metal tanks or small boats, where people made a living by fishing. Large nets tied to tall bamboo sticks and metal nets under the houses were set to trap large quantities of fish. Farmed fish goes to the markets in Saigon; some is exported. Although their living conditions did not reflect it, some families are reputed to prosper in the business.

As we moved through the waterways, we passed by houses with tiny balconies crowded with hanging laundry, potted plants, children, and even pets. Some had vegetable gardens right on the water. Families paddled by, waving to us.

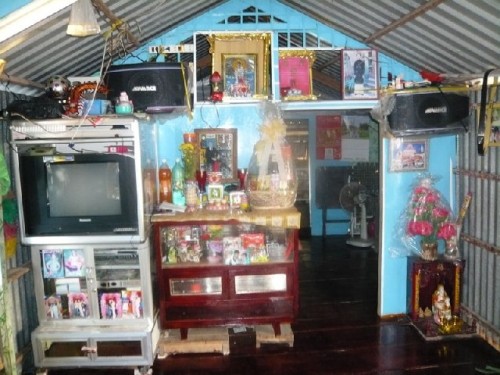

Our captain had his wife and two children on the boat. In addition to visiting them, we met a family who lived on the river in a tiny houseboat. This family made their own fish food by mixing rice husks with vegetables, and demonstrated how tasty it was by throwing handfuls into the water as we watched droves of fish scramble for it. On the way out, walking through the tiny, neatly-furnished living room, I noticed a small TV and the ancestral altar nearby. In this culture aging parents and ancestors command a great deal of respect. Bidding farewell to our gracious hosts, we returned to Chau Doc, where we boarded a speedboat to travel into Cambodia on the Mekong River.

Reflecting on this visit to Viet Nam, I was glad to have had a second opportunity to see the country. However, if this had been my only trip, my experience of Viet Nam would have been incomplete. For a full appreciation of the natural beauty and richness of Vietnamese culture, one must include the north, which is very different from the south.