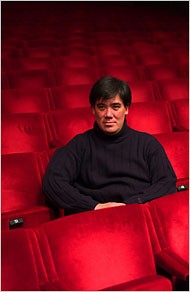

Maestro Alan Gilbert at New York Philharmonic

New Conductor Leads Adventuresome Program on PBS

By: Susan Hall - Sep 16, 2009

The first program Alan Gilbert conducts as new music director of the New York Philharmonic includes a world premiere of EXPO, by Magnus Lindberg, the orchestra's new composer in residence, Poemes pour Mi by the daring and innovative 20th century composer Olivier Messiaen, and the Berlioz Symphonie fantastique, which Leonard Bernstein recommended as a good way to get high.

The rehearsal for tonight's program (televised live on local PBS stations) was packed, even though the program was adventuresome. Inside the hall, for dress rehearsals, the first rows of the orchestra are called "the conductor's rows" and they are almost empty. This does not mean that the conductor's friends and family have not come -- in fact his mother is on stage as a member of the string section. These rows are designed to afford privacy -- we the audience can't hear the instructing, cajoling and or even the praise that's being given. After the Lindberg piece was performed, the composer leaped to the stage from the front row, to receive the applause and give notes.

Gilbert, in spite of his unconventional inaugural program, told an LA Times interviewer that he would take Haydn to a desert island with him. Haydn is "a good example of someone who retained his youthfulness...his music is witty and quirky and playful, mischievous..."

Gilbert's pedigree -- he is the son of two Philharmonic violinists -- precedes him as he takes the stage. Do other musicians come trailing their begats?

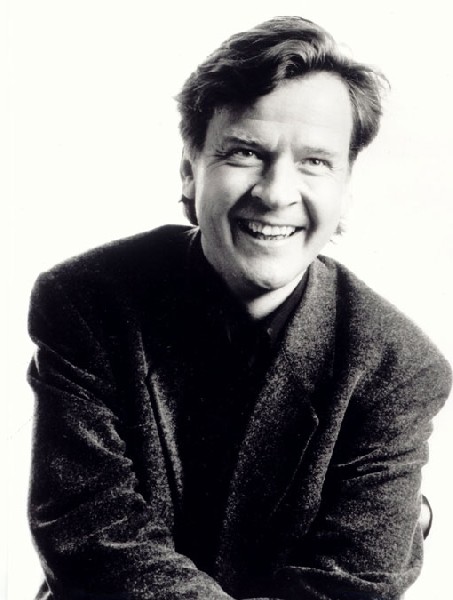

Gilbert's beloved Haydn was brilliantly recorded by Max Goberman, who has also entertained as conductor of On the Town, West Side Story, and Milk and Honey. Married to a cellist, he is the father of the producer of this evenings Live From Lincoln Center, John Goberman. Decades ago, John came up with the idea of live broadcasts from Lincoln Center, and persuaded the Chairman of the Lincoln Center board that these broadcasts were the wave of the future. They were. But Goberman's pedigree does not go around tagging him. Neither does that of Peter Serkin, the pianist son of Rudolph, or long time Philharmonic bassist, Orin O'Brien, daughter of a matinee idol in Hollywood films. Ms. O'Brien was a standout in bright acqua this morning. (She has played for the orchestra since the new conductor was a toddler).

Of course, were I a conductor, I would not want Mother (who played the violin) in my orchestra. But there was Gilbert's Mom in a modest brown and grey shirt and tights, behaving. Does Mr. Gilbert ever have the fantasy, once expressed by my young son when asked by his dentist what he would like to be when he grew up? "A dentist," he promptly replied. "And why," asked Dr. Bachman. "So I can be your dentist."

In the end, what goes into a musician does not matter. It is what comes out.

Magnus Lindberg wanted to express continuity in EXPO, and since he knew the concert would include Messiaen and Berlioz, those composers inform his creation. "Being influenced by references to masterpieces from the past is a natural way to feel I belong."

The Messiaen song cycle is one of the composer's early works. Some complain because the Mi or wife for whom it is written is said to be "an extension of her husband."

Messiaen described the cycle as "long, very tiring for the breath, and requires a very wide vocal range." It's brave to tackle these songs.

For Messiaen they express Wagner-like Liebstod or love-death. A student sitting behind me remarked that he thought Messiaen's mysticism might play better in America than it does in the composer's native France.

In the sixth song, "Your Voice," the wife's voice is compared to that of a bird. You can hear birds in the score. Messiaen wandered around the woods transcribing bird songs, which he claimed were accurately rendered in his music. Ornithologists, however, are unable to recognize the species and musicians can't imagine there are birds who sing in Messiaen's style.

About the Berlioz symphony his biographer wrote, "a vividness of imagery and an originality of sonic and formal invention that remain fresh and vital" comes from "its mastery of large scale musical narrative..."

Berlioz's extraordinary effects come from the use also of the well-worn minor ninth, the diminished seventh and the augmented sixth. Gilbert too builds on a traditional base and then flies.

While Berlioz was preparing for the first performance of this symphony, a lady in Paris wrote to Berlioz's sister, "I was talking the other day to a great musician, and she said that he [Berlioz] is singled out among the young men. When people see him pass, they say, 'That's the man."

On the symphony's first page, Berlioz wrote, "My heart's book on every page." We can see this welcome expressiveness in Mr. Gilbert.

Watch him tonight, September 16, on your local PBS TV station.