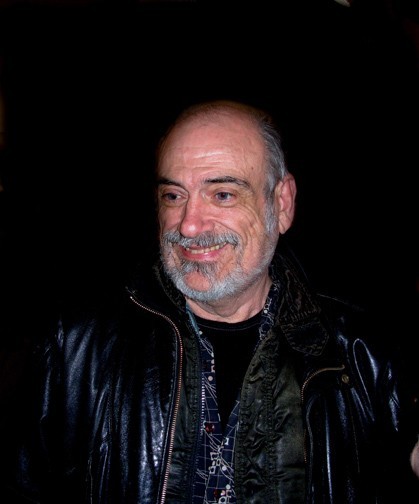

Domingo Barreres: Beer and Burgers

Exploring the Ambitions of Las Meninas

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 16, 2013

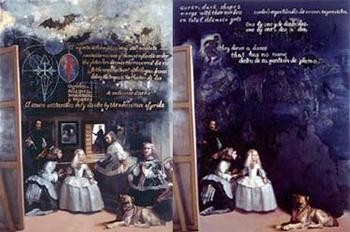

The Boston based, Spanish born artist, Domingo Barreres, showed a series of seven large canvases based on his analysis and interpretation of “Las Meninas,” 1656, by Diego Velasquez (1599-1660) at New York’s alternative space, White Box. The works, finished in 2001, had taken two years to complete. They were well received by critics with “picks” in the New York Times and Village Voice as well as a review in Art In America. It was not his first New York show, but the first in some time since the closing of Victoria Monroe Gallery, which in the past couple of years has returned to Boston, its original location.

Although none of the canvases have been sold the artist has mixed feelings about that. They represent some of his most important and ambitious works and he hopes to have other opportunities to show them as a group.

As we talked, the series emerged as an obsession. A means of acting out and through personal issues. In a survey of leaders in the art world several years ago “Las Meninas” was proclaimed as the greatest single work of Western Art. One may always debate the validity of such lists but unquestionably the painting is a masterpiece that has riveted and intrigued generations of viewers. It is an enigma and Barreres has devoted himself to studying and unraveling what he refers to as its “clues.”

We had been talking somewhat awkwardly for awhile. Although we have known each other since the late sixties, when he first showed with Sunne Savage Gallery, I reminded him of a bad review at the time, which he does not remember, this was the first time that we had sat down for a beer and burger and a serious discussion of his life and work. Actually, Domingo did not eat as he planned to join friends later for dinner as has been his habit several times a week for many years. And he was flustered when the waitress asked what kind of beer he wanted. “Just beer,” he said before settling on a Corona. And then, later, a bit reluctantly, another as I downed a second Sam winter seasonal.

There had been that difficult time, as is so often the case during an interview, however informal, or initial social meeting with someone you know, but don’t know, but want to know, and maybe will know, and maybe won’t know. And what the heck are we really doing and why? All that. The usual, but interesting questions, which we will get to later about birth, sexual preference, living with HIV, training, issues, stuff like that.

Then wham bam. “Las Meninas.” Dommingo titled forward in the seat, engaged me. Ignited. The room disappeared. Time stopped. Just what I had hoped for. Spectacular. An artist really pouring his guts out about the work. Without rules or limits. Locked and loaded. My head was spinning as I strained to absorb and remember every magnificent detail. He brought to it the passion and insight of an artist. Something you would never get in the latest research published in the Art Bulletin. No scholar can bring a painting alive for you like another artist. Particularly a richly gifted, brilliant and complex one like Barreres. Who also has a compelling and infectious sense of humor.

Although his series of large scale canvases includes a nude boy, posed like the Infanta Margareta Teresa, and a Cardinal, both self portraits, the theme is not about the sexual scandals that have rocked the Roman Catholic Church. The series was in process before the scandals became widely publicized. And he states that he was never molested by a priest although in confession, “I gave them many hints.” He had been struggling with his sexual orientation since an incident with an older boy at the age of three and a half. Actually, the priests told him to struggle with and overcome his urges and fantasies. Which he did. Including a marriage of some ten years. No, while his paintings include the erotic image of the boy/Infanta, he said with a great flourish, the primary issue is “ambition.” His seven related works include only one literal reference to “Las Meninas” a rather straight rendering of the dog. The rest is about what he calls “Tangents.”

From his long and detailed study of the masterpiece in the Prado Museum in Madrid, Barreres has concluded that the artist had a complex agenda. Foremost, he wanted to make a great and unique masterpiece. A painting for which no precedent existed. In the canon of art there was no painting like it. Although the Infanta is the center of the piece it is the artist, off to the side, peaking behind the easel, who is the true subject. How could the servant of the king, a court painter, make such a presumption? By an analysis of the space and perspective Velasquez stands at some seven feet, literally towering over all the other figures in the composition, which to emphasize the point, included dwarfs. Interestingly, Goya, when he painted the royal family, borrowed the devise of including himself in the composition but in normal scale.

At the time when he created the work, just four years before his death, Velasquez was frustrated and disappointed in his ambition to be made a Knight of the Order of Santiago, which did not happen until 1599. The dagger/ cross in brilliant red, now seen on the garment of the artist, was not added until after his death. It is also prominently displayed on the chest of the Cardinal/ Self Portrait by Barreres. As a trope for a similar ambition to be accepted as a great artist, a Knight of Santiago, as the culmination of an ambitious career.

Although Velasquez was the greatest Spanish artist of his era he was regarded as little more than a servant of the court by the nobility of the Knights of Santiago. He had failed to be admitted for some ten years despite the efforts of the King and Pope, according to Barreres. Accordingly, a part of the agenda of “Las Meninas” was that the artist needed to demonstrate his special and close relationship to the king. But the king, by then elderly, had refused to sit for a portrait for the past dozen years. So how to accomplish that without violating the will of the monarch? Also, Barreres believes that the queen was pregnant at the time which also prevented him from depicting her in that state.

So, voila, the brilliant device of the mirror on the back wall that catches the moment of the royal couple approaching the “studio” which is, in fact, the quarters of the deceased Don Balthasar Carlos, brother of the Infanta. But, to comply with the wishes of the king, they appear as a blur or smudge in the mirror and the queen is not revealed as pregnant. Thus Velasquez made his point about being the official painter to the king.

Barreres has also researched some of the political issues of the painting especially the fact that it does not depict the older daughter, Maria Therese, because she was not the much desired male heir. That son died. Maria Therese then married Louis XIV of France and the Spanish line was passed to a new dynasty. So there were political reasons why the younger daughter was depicted.

“The subject matter has nothing to do with the content,” he said. “It is a farce. A cover for the ambition of the artist. For me that is a reference for what I want to say. My work (the seven paintings) has to do with my own twists. But I only took the dog from the painting. The boy has the same pose as the princess but is naked. He is me. There is no me, just the context of the painting. A collage of the parts of the boy. The crotch (genitals) are from Caravaggio’s ‘Amor.’ The hair is from a 21 year old student of mine. I used Photoshop to make a collage of the elements. The boy carries Morning Glories. In Spain it grows year round, it is a weed, a creeping vine, very beautiful, but kills and chokes everything including trees. It is a climber. So there is the sense of me as a (social) climber. The dog has the instincts of the tamed wolf. There are bats in the sky. The viewer does not need to know all this but I like to follow the controversy.”

He discussed in detail each of the characters in the painting. The two Portuguese attending girls, Las Meninas, the Maids of Honor. The female dwarf as well as the male dwarf who is kicking the dog. I had always assumed him to be a boy, but Barreres insists that he was a dwarf and fool, dressed in forbidden red in the French style. Also the nun, is not a nun, according to him, but a widow and chaperone. The man next to her, the only figure in the painting not known and identified, is likely to be a body guard.

Then there is the man at the back of the painting, standing in the stairs through an open door. The second door on that wall is closed. In real life he was a man of similar position and status to the artist in the court. But if you follow the complex perspective, the artist is taller and stands above this man. An indication of the artist’s plea for superior rank. Finally, the artist is grouped with the figures, is of their world, but through his exaggerated height and position in the composition, is the only figure whose head elevates into the realm of art, signified by the paintings represented on the walls.

If “Las Meninas” represents the ambition of the artist for knightly status then what of the series by Barreres? Let us hope that it leads to a similar elevation. It certainly states a compelling case.

But, since that series, the artist has struggled. In 1966, with money from a Fifth Year travel grant from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, he bought a hut in the mountains of Spain, with two acres of land, for just $400. He travels there to live and work every other summer. Often what is done in that rustic studio he describes as playful and experimental. He has been inspired by the theme of 9/11 but has destroyed two bodies of work as too literal and unsuccessful. He continues to work with that inspiration and now feels the work is going well. Other than teaching at the Museum School, one night a week with his son, and two nights with friends, he just paints. There is just work. It is a simple life. Like a monk but devoted to art rather than God. “So you became a priest after all,” I said to him. “Actually I had wanted to be a priest,” he said.

Back growing up in Oliva, in Valencia, where he was born in 1941. In 1957, when he turned 16, he pleaded with his family, threatened to commit suicide, in order to live with a brother in Hartford and attend high school prior to enrolling in the Museum School. He explained that if he did not get out of the Spain of General Franco (who died in 1975) before he turned 17; he would be stuck and prevented from leaving. Remaining in Spain would have meant becoming the banker that his father intended. Only in America could he find his true calling as an artist. Reluctantly, his father, faced with the prospect of a greater tragedy, allowed him to leave.

Although he left Spain, arguably, Spain has never left him. It is in the work. Even though it evolved slowly after an initial phase of geometric abstraction (the paintings I didn’t like). But always it is subdued and subliminal never literal. The cones, for example, a motif in the work several years ago, referenced the dunce caps of the inquisition and the costumes of the self mutilating zealots, the flagellants. At the time we talked about those references. They were wonderful and compelling paintings.

The seven paintings of his “Las Meninas” series are about ambition. The need for culmination and recognition. A sense of heightened mortality. But he shudders at the though of a retrospective. “That would kill me,” he exclaimed. But he was diagnosed positive with HIV in 1989 and given a prognosis of just a couple of years. His lover of 16 years, Merritt, died in 1990. They had separated but were still close. Of that relationship, he stated with wonderful emphasis, “That was good.”

I asked if a sense of mortality had troubled him. He said that it did at first but not really any more. He has a sense of humor about it. When he retires, for instance, he doesn’t have to worry about how long his limited savings will last.

Domingo appears to be enjoying his life and work. He is grateful for his job at the Museum School, where he has been a great influence and much respected. It allows him to not depend on sales. He also states that he has had great relationships with his dealers: Sunne Savage, Bess Cutler/ Pat Stavaridis, Victoria Monroe, and for a number of years, Howard Yezerski. He has never felt pressured or told what and how to paint. And they have all believed in the work.

Yes, he has been recognized as a great Boston artist. But, he would like to be known as more than that. File that under ambition. A topic he has explored in depth.

Reposted from Maverick Arts Magazine.