Gerry Bergstein: Beer and Burgers

Redefining Boston Expressionism

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 16, 2013

Asked if he is a Boston Expressionist in a tradition that started most notably with Hyman Bloom, Jack Levine and Karl Zerbe back in the 1930s, the artist/ painter Gerry Bergstein paused and reflected over his Sam Adams seasonal winter white ale. He was my latest drinking buddy in the ongoing, Wednesday nights, Beer and Burgers With… series of meetings, social events, interviews.

It’s a tough and complicated subject. The origins of Boston Expressionism and how that influenced and played out, from generation to generation, etching a deep groove in the Grand Canyon of local sensibility. It’s a turbulent river run, white water rafting, that the DeCordova Museum and Sculpture Park, some time back, botched badly with an uneven show and worse, a deeply flawed and inaccurate study and catalogue. Given the importance of the subject it enraged me at the time as I set forth in a scathing review in the Patriot Ledger. |

If, indeed, Bergstein is a Boston Expressionist he certainly picked up the scent and line of descent from a master and teacher, a legend of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Henry Schwartz. Henry is a very great artist who did not pull out a post project slump following his retrospective at the Fuller Museum of Art. Since then he has spent a number of years under managed care and not answered letters or welcomed visitors. In his day, the obsessed and eccentric Schwartz was a giant and the frequent hero of his elaborate narrative paintings. In one, Henry in tails is depicted conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra, with some of his artist friends holding down chairs in the string section. Of course, the orchestra was performing Mahler, Brahms or the German romantic composers that Schwartz, an enormous, lumbering man, loved with such a passion. Yes, Gerry acknowledged the influence of Henry but also Barney. That is the very different, shy and diffident realist, the late painter, Barney Rubenstein.

To make his point Gerry explained how Henry would say, “You can’t do that, it’s terrible. But Barney would shrug and say, yeah, that’s nice. Go ahead.” So that tandem of teachers were the green and red lights for the young painter. “Shelburne (Thurber) and I became close friends of Barney and we would frequently meet for dinner.”

But the tradition of Boston expressionism while glorious is also treacherous. As the DeCordova curators blundered into. It has its egregious, maudlin, sentimental side. A case in point is the dreadful retrospective of the work of David Aronson now on view at the Boston University Art Gallery. I forced myself through the exhibition in about fifteen minutes just to be reminded of how much I hated the work. It’s just that which has killed the avant-garde reputation of Boston as a sentimental, literary, reactionary backwater.

Part of that is the notion of Jewishness in the work. Jack Levine, who departed for New York after being discharged from the Army after WW11 told me during the considerable time I spent with the artist some years ago when David and Nancy Sutherland produced a documentary film on him, “I came upon by Hebrew subject matter quite honestly.’ ” In a notorious review, Hilton Kramer wrote about Bloom, who was much admired by the Abstract Expressionists, “I could smell the pastrami as I was walking down the hall to the gallery.” When Kramer was a speaker at Skowhegan, in Maine, some years back, I asked him about the quote. “That was just a matter of one Jew criticizing another,” Kramer replied with no hint of remorse.

So this is a bit of a swamp to get through. By now Gerry’s first of three pints was drained. I was still sipping the foam off mine but also busy scribbling notes. “Yes I am a Bostonian,” he said but grew up in NY and came to study at the Museum School. “And, yes I am an expressionist but also a pop artist I guess. I was not interested in Zerbe. Maybe a little bit in Bloom. I didn’t care for the sentimental Jewish aspect of Boston Expressionism. I am not interested in its sanctimonious sentimentality. I am a Jewish artist. But from a cultural rather than religious point of view.” We would get deeper into that later.

But the real catalyst to the dialogue occurred when I mentioned Philip Guston (1913-1980). For many years Guston came to Boston on a weekly basis to teach at Boston University. There he may have undone the damage inflicted by Aronson and the other sentimentalists. Guston represented a tougher, grittier aspect of humanist expressionism. He had enormous influence on students of which Jon Imber is an example. Gerry never stated that he knew Guston but the influence proved to be crucial.

When the young artist first saw a Guston show at the Marlboro Gallery in 1969 it caused an epiphany. At the time Bergstein was making surreal paintings in the tradition of Magritte. “When I saw that show my thought was that this is garbage,” he recalled really leaning into the conversation like sails filling with a zephyr. “The drawing was bad and the color was awful. I remembered it as one of the worst shows that I had ever seen. It bugged me for years.”

It was just that irritation, the grain of sand in the oyster that I remarked on in 1980 when I wrote about his first one person exhibition at Lopoukhine Nauduch Gallery on Congress Street. He was ten years out of art school and slowly coming into his own. “When you wrote about my show, my first professional review in the Patriot Ledger, I thought you were the apogee of the Boston art world.” We had a laugh about that. I tried to recall and describe the work. I remember at the time talking with him in the back room of the spacious loft gallery and recalling how shy, awkward and socially inept he was. These are still qualities in his persona but now polished and refined to perfection: His amusing, passive aggressive persona. Stock in trade, magister ludi. At the time I was confronting the young sorcerer just learning to wave his wand. “Thick paint,” I said recalling that conversation. “I asked you about the thick paint. Globs of it. In relief off the canvas. I was amazed as time went on that you mastered the techniques of trompe l’oeil to create illusions of those same visual perceptions. The work never really changed but the craft did.”

He described one of the works in that seminal exhibition some 25 years ago as a dark room with a bed and a large form under a blanket. The TV in the room was smoking a cigarette. There was an empty refrigerator. “The guy in the bed was me,” he recalled. “It was about my life then when I would come home to my firetrap apartment, turn on the TV, have some wine, smoke cigarettes, and call people on the phone.”

Back then he was the ultimate lonely, nerdy guy who would seem to have grim prospects and little luck with women. Years later I was a guest at his loft wedding, a memorable occasion, to the artist Judy Haberl. In December of 1992 he remarried to an artist Gail Boyajian who is also a trained architect and designer of their summer retreat in Vermont.

As he was struggling to develop a style in the early 1980s more and more of Guston sunk in. “I was insecure as an artist,” he recalled. “I had done trompe l’oeil in Henry’s class but I didn’t think I could be a realist or figurative painter. What I most hated about Guston became a part of my own work. I came to realize what Guston was really about: Appetite, ambition, mortality and corruption. I came to realize that they were very smartly painted. They represented an explosion of emotional and rigorous formal strength.”

Bergstein was not alone in coming around slowly to Guston who took a lot of hits for abandoning the style of abstract expressionism to come full circle to the themes of his social realist roots in the pre war era. At time time, for example, Guston contacted the MFA and offered the curator, Ken Moffett, any painting he wanted out of the studio. The response was that they would be interested in a donation of an early work from the abstract expressionist period. Today a later Guston hangs on the wall of the MFA. Another testament to its lack of perception. Who knows what they finally paid for the work after the entire world came to acknowledge its importance. Only later would Guston be understood as the catalyst for the Neo Expressionism of the 1980s. That was also prime time for Bergstein who had many national and international exhibitions under as a Neo Expressionist. He did well with Stux Gallery which later phased him out when they moved to New York. The artist currently has no New York gallery but hints that a change is imminent. Of his oeuvre Bergstein reports that he owns nothing from the 1980s, some works from the 1990s, and some from the past five years. He has steadily sold most of the 20 or so works he produces each year and has a number of very loyal collectors.

Bergstein is on my short list of top five Boston painters. A couple of years back I included him in a show “Los Cuatro Grandes” along with Robert Ferrandini, Domingo Barreres, and Miroslav Antic (since moved to Florida but who showed at Kidder Smith Gallery this season). Rethinking, today I would add Thad Beal to that mix of top Boston painters. Note the word painters. To say who are the best artists is a much tougher question. I took a lot of heat for that show. But where there is smoke there is fire. It was right at that time that Ferrandini suffered a stroke and Gallery Naga will present a comeback show during the fall season.

Knowing Gerry’s work over the years has also been to know Gerry himself. So much of his life, hopes, fears, hang-ups, habits and obsessions have been in the work. Like Guston there was a lot about smoking. He finally quit some time back. And junk food. The other night I watched him vacuum a burger and fries. Clearly there is a hunger in the man, an appetite, you can see it in the work. The way that he devours subjects and makes works that are visual orgies and feasts for the eye. Sometimes looking at them gives me heartburn. Like too much mustard swathed on my Carnegie Deli pastrami. I just can’t resist. I seem to be as compulsive about sucking up Bergstein’s paintings as he is obsessed about making them.

There is pathos in the many self portraits. Some recent ones involved anguished grimaces. Fragmented figures, stitched together like Frankenstein body parts. Do they add up to a whole? Can you make a man from such severed limbs reattached?

We talked about a show I didn’t like. When his dealer, Howard Yezerski asked me about it I said that it seemed transitional. As a critic and friend, an ally of the work over a long time, there is some anxiety of not liking a particular body of work. There is conflict about making those thoughts public with its potential to damage the feelings and reputation of the artist. But also a sense of responsibility to not back off. To raise issues even if they inflict damage. Part of the job description of the critic. Or just back off and take a pass until the next show. Hope that the work gets back on track. Earlier this year I had a dialogue with an artist who felt betrayed by a review. We had to talk it through. She stood by the work, felt I got it wrong, but also revealed that it came during a vulnerable time.

Although I did not write about that show Gerry knew exactly what I was referring to. It had indeed been a transitional show and period. He recalls being very depressed but was booked for a show and felt he could keep the commitment. So I had been right about my response and in hindsight perhaps should have written about it. Artists need that feedback and dialogue particularly during period of difficulty and transition. It is what critical writing should be about.

In addition to its heavy theme of angst there is also a lot of humor in Bergstein’s work. He is a very funny guy to talk with. We had more laughs than tears over our beers. But Gerry also gets nervous and self conscious about just how much he is willing to reveal of that dark, tormented, inner persona. Perhaps it explains why over the years we have been more friendly than friends. We have never felt entirely comfortable and secure with each other. But it is exactly that insecurity that has kept a vital edge to the relationship. He can’t let his hair down because he doesn’t have any. Once we had gotten beyond the basic facts, as reported here, about half of the rest of the meeting topics were introduced with, “This is off the record,” or “Don’t quote me.” I said I wouldn’t but informed him that it would go into background. He is very loyal and protective of individuals who he refers to as having been good to him. But there were winks and hints of what he really thinks. You can chew on that a bit.

But I pressed him on the element of humor in the work. I think it is essential in an understanding of his creativity. “It is a humor born of pain,” he explained. He listed such sources and influences as Seinfeld, Groucho Marx, and Woody Allen. In this tradition he explained, “I am very Jewish. The alienated Jew of Woody Allen and Groucho. It is not religious. It is cultural. I love the jokes and the way that they are turned on myself. The idea of the paradox.”

In particular he talked about Groucho as an unhappy and tormented man. “He wanted to be a doctor,” Gerry said. “But his mother insisted that he go into show business.” There is always that angry edge to Groucho and from that the brilliance of the comedy. He explained it with an anecdote of how Groucho married a non Jew. When his daughter applied for membership in an upscale country club, she was turned down because she was half Jewish. Groucho wrote to the admissions committee that if that was the case would it be ok if his daughter bathed in the pool up to her waist.

Gerry talked about the importance of this culture and humor while growing up in NY. He loves anecdotes and jokes. When visiting his elderly parents recently they urged him to call a cousin as it was his birthday. Making the call the cousin was less than appreciative, “Who told you it was my birthday?” was his response. Doesn’t that speak volumes.

Then Gerry told a joke. “A man was on his death bed when he smelled a cake baking in the over. That cake smells so good he said to his wife. Can I have a piece I’m starving. What, you should kid me, she answered. I’m baking it for the funeral.”

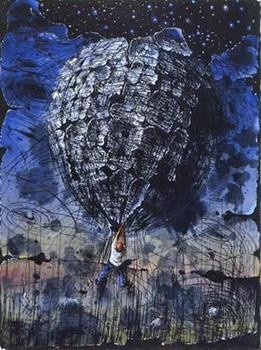

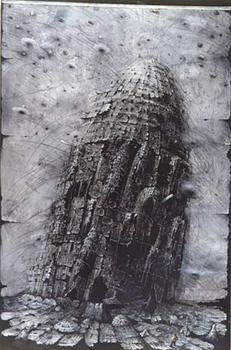

More than just funny the work can also be cosmic and zany. It has it puzzling, deep and gonzo side. When discussing artists he loved and admired, Guston and DeKooning, but also Velasquez and Breugel, he discussed a recent trip to Vienna with Gail to see the great room of Breugel paintings. In particular, the magnificent “Tower of Babel.” That has been a major deconstructed theme in the paintings of the last several years. These dark and foreboding works have not entirely been understood by critics and curators. For me they are among his truly most magnificent works. They explore his dark side with more freedom and energy than anything in the past. Because the mound or mountain can take any inventive form and shape he has never created with less restraint. He agreed with that thesis and added that they were also inspired by the mound in the living room that Richard Dreyfuss was making after his “Close Encounter of the Third Kind.”

Perhaps we may conclude that for Bergstein the primary concern is perceptions of time and their lack thereof. We now know that there is no time. It is a fiction and a matter only of position and perception. What Einstein viewed as Relativity. But that he has since been proved wrong. That there are multiple positions and perceptions and hence no possible finite time. Despite the constant ticking of clocks internal and eternal. So it is that psychic space time continuum that best describes Bergstein. A kind of pretty funny, culturally Jewish, fairly anxious, space time traveler. Far out.

Reposted from Maverick Arts Magazine.