An Unsymposium for Gerald and Sara Murphy at Williams College

Lost Generation Remains So

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 17, 2007

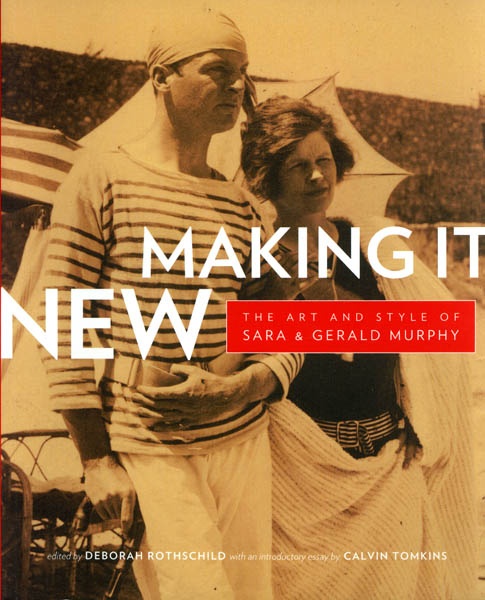

All summer long the reviews poured in for "Making It New: The Art and Style of Sara and Gerald Murphy" curated by Deborah Rothschild who is retiring at the end of the month from the Williams College Museum of Art. The hook of delving into the glamorous epicenter of the Lost Generation and the couple who inspired the famous quip that "Living well is the best revenge" or the curt observation by F. Scott Fitzgerald that "The rich are different from us" proved to be irresistible.

The exhibition including all seven of the surviving paintings by Murphy from an oeuvre of some fourteen finished works remains on view at Williams through November 11. It travels to Yale University from February 26 to May 4 and to the Dallas Museum of Art from June 8 to September 14. While the actual works of Murphy are few in the exhibition there are a total of about 1,000 registered objects including a handful of works by the mostly French and expatriate Russian artists he knew, studied with, and was influenced by in Paris, as well as an overwhelming number of letters, photographs, and documents. They induce a saturation in the world and lifestyle of the charismatic, inventive and socially skilled, rich, American couple and their fabulously gifted, famous, often troubled and complex friends.

While the exhibition, accompanying catalogue, and Unsymposium capture the zeitgeist of the Murphys his achievement as an artist, sources and influences, and a thorough critical analysis of the oeuvre, remains a work in progress. There is so much emphasis on the ephemera and artifacts of the Lost Generation, the colorful and lurid stories, the glitter and glamour, that the core and substance of the work, and its connection to other literary and visual arts masters of the era remains, well Lost.

Yes, there was an avalanche of media coverage in a range of publications from venerable to ephemeral. But every review I encountered furthered the sense of frustration. Typically, they focused on the milieu, ambiance and entourage of the couple, rehashing the basic facts set forth by biographer Amanda Vail in her award winning book "Everybody Was So Young: A Lost Generation Love Story." The majority of the reviews spent at best about twenty percent dealing with the work itself and this routinely occurred in the last third of the essays. The usual approach was to sell us on the fabulousness of the Murphys and the incredible Lost Generation and, oh yes, he was also an artist.

Am I terribly wrong on this but aren't museums supposed to focus on the work itself, and place it into a larger context relative to work of its period? Just where do the surviving seven paintings by Murphy sit in the canon of American modernism? The Williams exhibition represents an interesting, very successful, widely acclaimed but different approach. Its greatest accomplishment is archival and documentary creating a complex tapestry of the social history and biography of a fascinating era when so many gifted Americans imbibed what Stuart Davis referred to as "The Paris thing." Significantly, Marcel Duchamp presented his American patron, Walter Arensberg, an ampoule of "Air de Paris (50cc of Paris Air)" upon returning from France in 1919.

Were the Murphys more than gracious and gifted dilettantes with an ability to draw to them the best and brightest? There was a phenomenal brilliance to Murphy's ability to enrich what moved and excited him but also an inability to sustain and take his art seriously and ambitiously. The work is fascinating and evokes theories of anticipating Pop Art in its imagery. But might not the same argument be made for the 1921 Start Davis painting "Lucky Strike?" Did Murphy know of that work when he made a similarly proto Pop painting "Razor" in 1924 or "Cocktail" in 1927? The aspects of social sculpture and performance pieces with food as art, were discussed in Rotshchild's presentation. She compared the Murphys and their flair for hosting and entertaining as an art form to the work of Rirkrit Tiravanija and other contemporary performance artists. And what of other similarly gifted, wealthy, American dilettantes such as the fascinating Harry Crosby who founded Black Sun press? What comparisons might be made between the Parisian sources and inspirations of Murphy (1888-1964) and those of Patrick Henry Bruce (1881-1936), Man Ray (1890-1976), Morgan Russell (1886-1953), Stanton MacDonald Wright (1890-1973), Alfred Maurer (1868-1932), and Stuart Davis (1894-1964)? How did their social network interact with and overlap the salon of Gertrude Stein (1874-1946) and Alice B. Toklas (1877-1967)? What about the charismatic Mabel Dodge (1879-1962) who arrived in Paris with John Reed (1887-1920) in 1913 before moving on to a villa in Florence?

A clue to the conundrum lies in the title of the exhibition "The Art and Style of Sara and Gerald Murphy." This is an intriguing conflation. It presents high art, the handful of paintings by Murphy, on a level playing field with their remarkable Style: A thesis that places his wife Sara as an equal in this exhibition. In fact many of their circle of friends from Fitzgerald or Ernest Hemingway and Pablo Picasso may have been more attracted to her than to him. There is the matter of his now much explored sexual ambivalence. While he remained closeted and fought bisexual urges they were a loving couple "A Lost Generation Love Story" devoted to three children. They suffered the death of two sons. Some of the most poignant documents in the exhibition are letters written to them in sympathy for their losses.

Major exhibitions devoted to previously obscure artists and their work have a way of encouraging as well as limiting further inquiry. Given the scale and critical success of this exhibition it is unlikely that it will be attempted again during our lifetime. It will stand as the definitive treatment. While the material will never again be assembled in this profusion there are important questions that remain about the work itself. These are what we hoped would be addressed in the Unsymposium and why it proved to be provocative, indeed capturing the flavor and spirit of the Murphys, but passed on the opportunity to dig deeply. The title of Rothschild's presentation "The Surface Is Part of the Depth" was too revealing of the curator's troubling strategy.

In the "spirit" of the Murphys the "Unsymposium" attempted to combine several scholarly papers with interludes of fun presenting song and dance as well as readings from "Tender Is the Night" by undergraduates playing jazz (a talented young trumpeter with good feeling leading a mediocre quartet) and enthusiastically performing steps demonstrated by Sandra L. Burton, the Lipp Family Director of Dance and Assistant Professor of Physical Education at Williams. She showed us how to do the Charleston, Shim Sham, Mess Around, Truckin, and Shorty George. At the end of the "Unsymposium" John Kinder demonstrated how to make some of the cocktails that Murphy was known for. All of which was entertaining but cut into the limited time of an occasion for the scholarly study of Murphy, his work and era.

Instead of undergraduate skits and demonstrations of how to make a perfect Manhattan it would have served a better purpose to bring together the scholars for a panel discussion with an opportunity for questions from the audience. Amanda Vaill presented "The Invented Part" which did not explore beyond her prior work on the Murphys. It is all too evident that she is a phenomenal biographer but not an art historian. The papers by Harold Koda "Miserabilisme Deluxe: A Strategy of Chic" and Kenneth E. Silver's "Gerald Undressed" were fascinating and richly informative. We would have preferred that the program chucked the entertainment and inserted yet another scholarly paper. Left off the table was the important topic of the Murphys as sources for the literature of the Lost Generation; or their involvement with the Ballet and Theatre and its influences on his paintings. They worked in the scenery shop of Diaghilev and this surely influenced the scale and theatrical style of the enormous (lost) "Boatdeck" which was a great success when shown in 1924.

Koda, the Curator-in-Charge of the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, contrasted the opulence and exotic Orientalism of Poiret and the elegant, classic simplicity of Coco Chanel. While he brilliantly provided an overview of the high fashion and style of the period of the Murphy tenure in Paris in the 1920s it was difficult to absorb a direct connection. The matter of Murphy's love of costumes and role playing as an aspect of a closeted gay persona was presented in Silver's paper. He discussed how Murphy was an exhibitionist who liked to take his clothes off or to wear as little as possible. Rothschild in her research discovered some remarkably revealing images of Murphy posing nude on his yacht the Picaflor photographed by Man Ray in 1925. Silver discussed an astonishing image of Murphy wearing a thong between a fully clothed Vladimir Orloff and Richard Cowan in a conventional bathing suit aboard the Weatherbird in 1934. Or Murphy nude, strategically holding a bouquet of flowers, in front of Villa America in 1932. For Murphy taking his clothes off was an avant-garde, conceptual statement. Or, arguably, an aspect of his closeted narcissism and a gay signifier.

The most significant part of Silver's paper was an effort to treat the embedded symbolism of Murphy's complex and disturbing "Portrait" (lost and known only from a black and white reproduction) from 1928. The disembodied, synthetic cubist work is a signifier of a need to express an embedded conundrum. In this part of his talk Silver discussed the matter of "gaze" and being the object of such attention as well as its significance. This drew him into an aspect of art theory which was beyond the general audience but he interjected "you know what I mean" and apologized for the art speak. But this is precisely what I had hoped for more of.

Thanks to the exhibition, catalogue, Amanda Vail's wonderfully warm and sympathetic biography, and a selective rereading of the classics of the Lost Generation in the past couple of years, including Hemingway's withering treatment of them in "A Moveable Feast," I feel like I know a lot about Gerald and Sara Murphy and their fabulous circle of friends. But in too many ways it seems like the morning after a terrific cocktail party recalling glittering and witty snatches of conversation. It was all great fun but just who are those people? Perhaps this is as much as we will ever know and arguably why they call them the Lost Generation.