The Dishwasher Dialogues: Paris Highlife in the 1970s

La Carte Orange and Les Toilettes à La Turque

By: Gregory Light and Rafael Mahdavi - Sep 17, 2025

La Carte Orange and Les Toilettes à La Turque

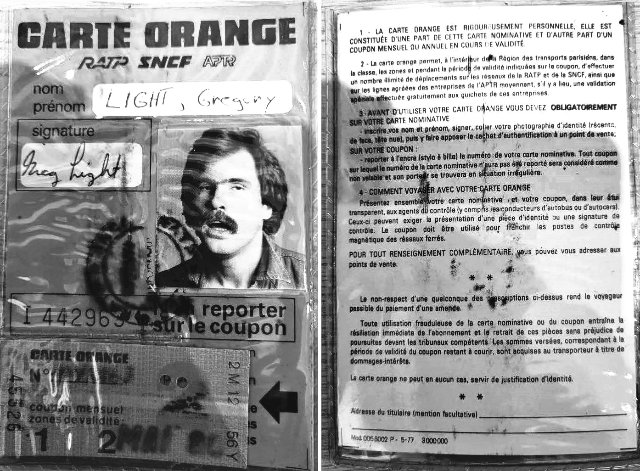

Rafael Mahdavi: As I took out my apartment key, my carte orange fluttered to the floor. It landed silently on the landing parquet by my apartment door and at the moment my memory came alive. I remembered how every first of the month you’d burst into the restaurant, Greg, holding your carte orange in the air, then announce, ‘here it is, ladies and gents, got my carte orange for the month, I’m set, I can go anywhere in Paris with this piece of plastic; that’s like going anywhere in the world, as we all know right now Paris is the world.’ The carte orange was a subway pass with your picture on it. You renewed it once a month, and it allowed you to travel wherever and as often as you wanted on the metro and buses of Paris. The pass was second class, unless you splurged. In those days the metro had first class carriages too.

Greg: Thank you for mentioning la carte orange. I will confess to going a bit overboard with its praise—maybe more than a bit overboard. The day, once a month, when I purchased that small new paper billet for my carte orange was sublime. I almost said ‘somewhat sublime’ but it really was sublime. Mobility was freedom. It awarded me freedom. To Paris no less. I still recall one very specific day when I purchased a monthly ticket in one of the metro stations on ligne 4—from the Porte d’Orléans to the Porte de Clignancourt line. My line. I remember it because I also picked up a brand-new plastic cover the card slipped into. Laura was with me. I remember holding up the card in its clean new plastic sleeve and saying to her with all sincerity that this single purchase gave me more pleasure than any other thing I bought in Paris. Admittedly, I was not buying a lot of stuff back then, but it pleased me more than buying beer, wine, food—not trivial purchases. I’m sure she thought I was crazy. She laughed. I think with me. Not at me. Maybe a bit of both.

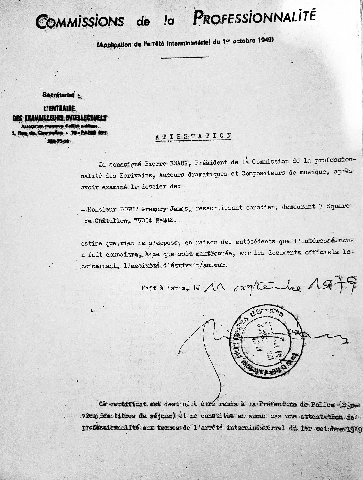

Greg Light: You must remember, in the first three years of my stay in Paris—until eventually securing a carte de séjour on the basis of being a “poet” (the benefits of which never came close to those offered by a carte orange)—I was an undocumented immigrant, or whatever the relevant authorities may have called it back then.

Greg: I will give them their due; they never cared about my presence much, no matter how dreadfully I disfigured their language. I found their disinterest in me, always with an underlying air of disdain, positively liberating. Despite being scowled at and frowned on for our all too frequent frivolous and inane public displays of lunacy— ’American Infantilism’ according to the disapproving French wife of one of our friends—we were grudgingly tolerated.

When I look back on it now, I understand my whiteness cloaked in a student-artist façade provided me with a dispensation not everyone was afforded. The idea that I might be deported never entered my mind. After all, I had my carte orange. My photo and name were on it. It gave me a Parisian identity of sorts. More importantly it gave unlimited travel throughout Paris and its banlieue. All for 40 francs––eight dollars. It was affordable. I could earn that in four hours at Chez Haynes. It was like giving a pass to Disneyland to a seven-year-old today, except this pass was to a land much larger, much more exciting, much more alive—an historic and cultural utopia.

Rael: On winter days, the metro was also a respite from the cold. Chez Haynes was a warm place too, but in general, keeping your apartment warm, no matter how small, in the Paris winters was a problem. Few people have written about the indoor heating issue in Paris; we often hung out in cafés and bistros. We dreaded the electricity bill, and we thought twice about ramping up the electric heaters. We found ingenious ways of slowing down the electricity meter by placing a hefty magnet on top of it or with a jeweler’s drill making a minute hole and slipping in a piano wire to block the spinning cogwheel. We spattered paint on the meter to camouflage the hole for the piano wire, and of course, we made sure to take out the wire or the magnet when the meter reader came around.

Greg: We did what we had to do to live. That and a bit of luck sufficed. And we did have luck. Finding my flat was a genuine fluke—a friend of a friend of a friend thing. Harry and his cousin Wendy came to my rescue again. I never worked with Wendy at Chez Haynes, but I remember an odd story which Harry told about her riding on the metro with her mother who was visiting her from Pennsylvania. They were sitting on the strapontins, the fold-down seats next to the doors. At one of the metro stations the door opened and a strange man on the platform suddenly reached through the door and grabbed Wendy’s breasts. Just for a moment. Then the door shut, and the metro continued on. After a moment’s silence, Wendy’s mother said: ‘You know Wendy, I think that young man thought he knew you’, assuming, perhaps, Wendy had a multitude of romantic liaisons stretched across the Paris Metro system.

Rafael: I worked briefly with Wendy at Haynes. I never got to know her. She sounds like a person willing to take risks, open to adventure. Having her breasts fondled, albeit briefly in public and not going ape shit about it, well, that makes for a cool head. In those days in Paris going to the cops with this story about male aggressive behavior wouldn’t have done much good. That, I’m sure of.

Greg: Wendy’s friend was a forty-year-old American woman who was unexpectedly leaving for Cairo with her brand-new Egyptian boyfriend. She was going all in on him and needed to sublet her flat near Place d’Alésia in the 14th arrondissement quickly. She guaranteed me three months which even I thought was optimistic. But the bet must have paid off because she never returned, and I was able to convert the flat into my name six months later. Only a month into my stay, with no papers—not even a carte orange—and I had a permanent home.

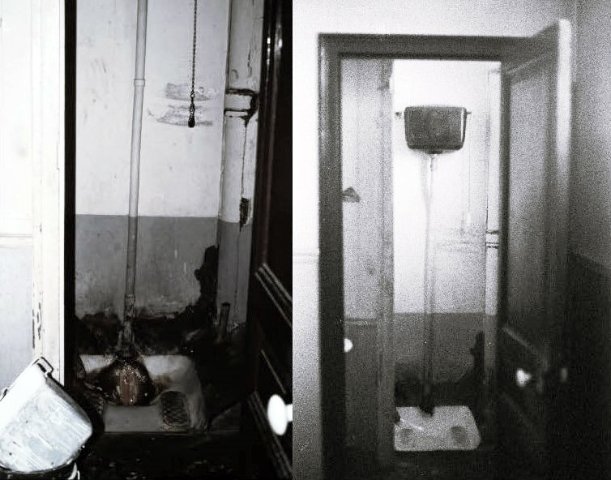

Greg: Not that my living space was luxurious, or even blue-collar. It consisted of two maid’s rooms on the top floor of a five-floor walk-up building. The building was nice in a bourgeois sort of way, with thick carpet on the stairway until the last set of stairs. The maids, I guess, did not deserve carpet. There were five rooms in total on the top floor. Except for my two rooms, they were all empty. Nobody ever came up to the top floor but me. My two rooms were in the middle, linked by a doorway, knocked through to make it look like it was an apartment. The two doors to the corridor remained, one of which was permanently locked and the other functioned as my front door. It entered what became my living room. The finished look didn’t include much of a kitchen—a short counter with a little sink, cordoned off with a couple of ceiling high cupboards dividing it from my bedroom and writing corner. So, all in all, not bad. Except there was no bathroom. There was a shared ‘Turkish toilet’ (hole in the floor) down the hall, and a foldout shower hanging off the inside of the front door in my living room. On the other hand, both rooms had large beautiful French windows which opened out onto a medium size cobblestone square. The view ‘out’ was incomparable, even if the view ‘in’ had much to be desired.

Greg: It was impossible to get in or out of the apartment if the shower was not folded up. So, each time I took a shower, I had to unfold the plastic platform from the front door, pull a shower curtain around the platform, hook up a shower hose to the tap in the small hot water heater over the kitchen sink, connect another hose from a pump underneath the shower platform to siphon the used water back into the sink, get in and turn on the water. Voilà! Afterwards I folded the whole unit back up and pushed it back against the door. It worked well when I remembered to turn on the pump. Which I mostly did. But not always. As for the WC, I was the only one living on the top floor, so it was all mine. Along with porcelain footpads next to the porcelain hole in floor, the room had a sink and a mirror and a soap dispenser. I disinfected them all, thoroughly cleaned the room and painted it. I would be genuinely hard put to say I have had a better, more hygienic toilet since then.

Rafael: Mais oui, mon ami. À la turque. We also called them squat jobs. And when you flushed and weren’t out of there fast enough you got a urine shine on your shoes. And don’t forget the toilet paper or your apartment key. Down the hall you could find yourself, without paper, without your apartment key and your pants down by your ankles.

Greg: You are right! It was all mine, so I sometimes walked naked down the corridor in the early morning. Until the day my apartment door closed (the wind?) and locked behind me. I had no key with me and hesitated to call for assistance as I was in a state of complete undress. The doors were solid, but I leaned back against the stairwell banister and eventually kicked the unused door open. I was also able to repair the lock, but there was a permanent crack in the door which I disguised with paint. Thereafter, I hid a second key in la turque under the sink.

Rafael: There were squat jobs in most bistros, but if you got the urge and rushed into a café you’d see a neat little sign, oh so beautifully lettered, on the zinc counter: l’utilisation des toilettes est reservée aux consommateurs. You can only use the toilettes if you buy something. Most often you were in a rush, and you quickly ordered a coffee, paid, and headed down the steep stairs to the WC. Or if you only had to pee you could use those disgusting vespassennes, circular, metal structures on the sidewalks––only for men. You’d walk into these things and urinate. People walking by could see your legs beneath the metal enclosure and hear the pee as it spattered against the metal. How come you never read about that in the guidebooks?

Rafael: I must say, the French were very sanguine when it came to poop and pee. Nothing to be ashamed of, bodily functions. They didn’t have many indoor toilets, and they used a lot of perfume to keep the smell camouflaged and the perfume industry thriving. Although some days riding in the metro was an olfactory experience hard to ignore.

Greg: If my WC was your basic, rudimentary Parisian commode circa 1970, my reward was a telephone—a semi miracle. The waiting list to get a telephone back then was six years. I also had radiator heat included in my rent. It worked brilliantly for three seasons, disappearing in the winter. So free heat when my neighbors with the large apartments below were not using it—which they tended to do when the air turned cold. My little electric heater became an important and faithful companion until, you will remember, it disappeared into the bathroom of your second studio at 67 Rue de la Roquette when I left for London.

Rafael: Back to the carte orange. It was for working stiffs basically, but it gave us a sense of freedom. We never took taxis; that was for tourists. Every franc counted, and the carte orange guaranteed our mobility.

Greg: And la turque guaranteed our wellbeing.

Rafael: My toilette à la turque was still down the hall, and the hot water was iffy because some days, the Rube Goldberg contraption that heated the water refused to work. The gas came from a gas bottle underneath the sink, and that was iffy too, but my rent was cheap, and we knew we’d have one good meal a day at Chez Haynes, bless Leroy’s heart. That man was a cultural benefactor of the highest order; he enabled many artists and writers and actors and dancers to pursue their dreams in Paris. If you had the crazy idea of applying for any help from the government, you had to get legal, and we soon learned that those artists who did get a cheap artist studio had connections in the ministry of culture, which usually meant they had a relative there or were sleeping with their connection.

Greg: Government help? For heat? For food? For clothing? Really? Until you mentioned it, it had never ever occurred to me. I was just happy not to spend time in their correctional institutions. Although, after a bout of tonsillitis, I did spend a free week in the hospital having my heart examined every which way but up. I remember there were lots and lots of medical students in and out of my room all the time. So, I paid for my stay by being an instructional prop. Chez Haynes was our social safety net. It provided a warm home, hot meals, and talk, lots and lots of talk. Throw in a carte orange, baguettes, and my own private toilette à la turque and life was good.