Eva Hesse Retrospective

Curated by Elisabeth Sussman and Renate Petzinger

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 19, 2013

Eva Hesse

Curated by Elisabeth Sussman and Renate Petzinger

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

February 2 through May 19

Museum Wiesbaden

June 11 through October

Tate London

November 12 through March 9, 2003

Reposted from Maverick Arts Magazine, September 3, 2002

Through an unfortunate combination of curatorial politics and economic retrenchment, the poignant, insightful and influential exhibition of paintings, sculptures, drawings and installations by Eva Hesse, originally organized by former curator, Elisabeth Sussman, (with co curator Renate Petzinger), was later canceled by the Whitney Museum of American Art. This denied the all important New York audience the opportunity of viewing an exhibition which has been nominated for an award for best exhibition in its category by AICA an international organization of art critics.

When David Ross, the former director of the Whitney, left to assume a similar post, which he has since vacated, at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, he took the show with him but not its curator. This surprised some in the art world who noted that when Ross earlier left Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art to become director of the Whitney he took Sussman with him. She is listed in the catalog for the San Francisco leg of the world tour of the Hesse show as, Guest-Curator. Subsequently, the Whitney’s new director initiated a bit of curatorial housecleaning but, in this case, denying New Yorkers the opportunity to view one of the year’s most important international exhibitions of contemporary art.

This survey is less than entirely definitive and successful. It is weighted heavily to works on paper and the early paintings which are unfamiliar to everyone but Hesse scholars. And, perhaps, rightly so. More importantly, a number of definitive but fragile sculptures are illustrated and discussed in the catalogue but for reasons of conservation have not been loaned to the exhibition. Given the ephemeral nature of her experimental materials there may never be a truly definitive and entirely satisfying exhibition of this superbly original and influential artist.

If we are denied the opportunity of ever seeing the actual works of the artist in their complete range, any regular tour of contemporary museum and gallery exhibitions will reveal her ubiquitous influence. As an art critic comments in a video that accompanies the exhibition she receives a constant flow of slides from artists working in the manner of Hesse.

She may indeed prove to have been one of the most original and influential artists of her generation as she bridged the gap from the cold and reductive manner of minimalism, while drawing on its spirit and thesis, but expanding into abstract process works using found industrial materials and polymer resins. Compared to objects by Flavin, Serra, Judd, and Andre, for example, her works have a similar aesthetic but also the element of the funky and hand made. One may always feel her presence in the work which is precisely the human element that was edited out of minimalism. And, perhaps, it is this combination of abstraction, angst, and humanity that has made her such an inspiration and soul sister to so many women artists in particular.

The biographical data of the artist is both poignant and sensational. We will be brief. She was born in National Socialist Germany in 1936. Two years later she and her older sister Helen were a part of the Kindertransport to Amsterdam. Three months later they were joined by their parents and immigrated to New York, in 1939. The parents divorced with the father remarried and assuming custody of the children. In 1946 her mother committed suicide.

The professional career of the artist was brief but remarkably brilliant. She studied at Pratt and Cooper Union and earned a BFA from Yale in 1959. Her first one person show was with Alan Stone Gallery in 1963. In 1964, with the sculptor Tom Doyle, she lived and worked in Germany. They later separated. The breakthrough to her mature style appears to have occurred during this period and led to enormous production up through the last two years of her life when she endured several operations prior to succumbing to brain cancer in 1970. She was just 34 at the time of her death and her reputation today is based on a body of work that she produced over several years.

While we were very grateful to catch up with this exhibition in Wiesbaden, quite frankly, I did not care for the installation. The museum uses a diffused system of indirect lighting filtered through panels of translucent glass mounted on the ceiling. According to the conditions of the lenders and the conservation levels of the museum the gallery lighting ranged from dim to dull. That might have been acceptable for the works on paper but it proved to be annoying when viewing the paintings and absolutely infuriating when experiencing the sculptures. A guard who overheard my complaints on this subject to my wife Astrid kindly and somewhat subversively tweeked up the reostat and even followed us from gallery to gallery turning the lights down after we left. What an angel. It made an enormous difference.

Why have exhibitions if you need a seeing eye dog just to experience the work itself. How does this ultimately benefit the artist. Also, the curator or conservation staff took it upon themselves to dramatically interfere with the appearance and intention of the work. Under some of the wall reliefs, that had dangling ropes intended to touch the floor, there were white panels underneath the pieces. Clearly the artist never intended the works to be seen in this manner. It may make sense to a conservator not to let the material touch the floor, but, damn it, that’s precisely what the artist intended and this just ruined the experience.

Another work, Connection, comprising suspended fiberglass and polyester elements, was installed above eye level in a rotunda where one looked up into an elaborate ornate cupola. The decoration in the ceiling was spotlighted while the work itself was not. Just what was the priority here? Hey man, sculpture needs light. It’s that simple.

As the many examples of drawings and paintings from 1960-1964 make evident the young artist struggled to find her own style and identity. There were glimmers of what was to come but nothing particularly special or interesting in this period of post graduate juvenalia. It was surprising to see to what extent her concerns were with washy, abstract drawings, collage, surreal forms, painting, and two dimensional surfaces. But gradually there were elements of relief as the paintings somewhat awkwardly and stridently attempted to come off the wall.

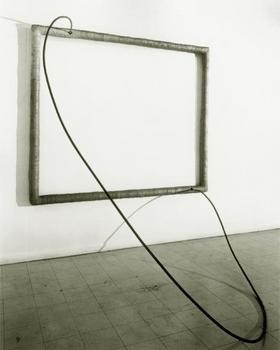

This struggle reached a brilliant and witty conclusion or synthesis with, Hang Up, from 1966. There is a large, empty, padded rectangle or picture frame. But there is nothing behind this “painting” other than the wall itself. This comments on the Renaissance architect Alberti who, in Della Pictura, a handbook for artists, advises that a painting is best seen as a rectangle evoking a window frame containing a vedute or view beyond. Hesse destroys that notion of the vedute by framing being and nothingness with existential panache and then takes the further bold step of adding a loop of thick wire attached to the top and bottom of the frame becoming, in fact, a sculpture. It seems to summarize her struggle to find a synthesis between painting and sculpture and in that essence is an important breakthrough work that allowed for a whole range of other possibilities.

In the mature work she experimented with the kind of industrial detritus that one finds along Canal Street and in Lower Manhattan. She particularly enjoyed such materials as telephone wire, rope, string, synthetic resins and such ersatz artist materials as sculpt metal, which Jasper Johns used to cover mundane objects and transform them into sculptures. Most importantly, she developed her own kind of visual vocabulary and syntax. There is no real way of describing or even experiencing the works other than in their own terms. In that sense they are what they are and not just what they are about or what they are made of. And yet they all seem to have her touch and presence, her style, manner and personality. In the last few years of her life and work she created a remarkable signature and identity.

Whenever New York museums mount surveys and overviews of periods, movements and collections, it is always a joy to see her work and how it just pops out of the norm and abyss. But this exhibition also reveals the growing pains and how that just didn’t happen over night. So this project dispels the notion of Eva the goddess emerging full grown from the fevered brow of the art Zeus.

The great loss of this show was the absence of a major rope piece. They are so wonderful and perhaps we will have ever fewer opportunities to view these endangered works. Also missing was the seminal Untitled (Seven Poles) from 1970 owned by the Centre Georges Pompidou. One of her last major pieces, it consists of seven, large irregular tubes of rough and lumpy surfaced resin. They seem to bend as they come in contact with the floor and become more of an installation rather than a single piece. It was considered too fragile to travel.

There was however a generous selection of the resin, boxed, wall reliefs, rows of resin tubes resting against the walls, and other signature works. It was particularly intriguing to view the labor intensive, obsessive compulsive works, Accession, and Accession 11, from 1967-1969. They comprised large cubes with open tops. We peer down into them and see an orderly pattern of clipped telephone wire fed into the space through a grid of exterior perforations.

Although some 32 years have lapsed since her death, indeed almost the mirror image of her life itself, it is amazing to state how fresh and contemporary the work still feels. In such a short time this artist truly accomplished so much. One senses enormous energy and obstacles to overcome; personal, professional, technical, aesthetic. So little time, so much to do, and yet the legacy and accomplishment are so enormous.