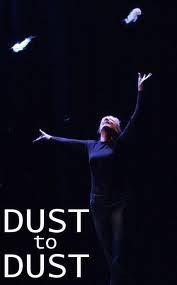

Elizabeth Hess in Dust to Dust

Stage Left Studio New York

By: Edward Rubin - Sep 21, 2011

Dust To Dust

Performed, Written & Directed by Elizabeth Hess

Technical Director: Colleen Toole

Stage Left Studio

214 West 30th Street – 6th Floor

New York, New York

Saturdays, September 10, 17, 24 @ 5:30 PM

Sundays, September 11, 18, 25 @ 7:00 PM

Tickets 800 838-3006

Tickets $20 at www.stageleftstudio.net

$10 for students with IDs.

For the past six years, slowly but surely, the small but choice, Stage Left Studio, created and run by producing director and actress Cheryl King, has been attracting the attention of playwrights, actors, and serious theatergoers, as well as New York critics. Dedicated primarily to solo shows, Stage Left has become one of the most sought after spaces in the city in which to develop, experiment, and showcase new works.

Last year their production of Batman & Robin in the Boogie Down written and performed by Juliette Jeffers was nominated for Outstanding Solo Performance by the Drama Desk. Currently walking in Jeffers’s footsteps is Dust To Dust, a stunning, 30 minute theatrical work, written, directed, and acted to a fare thee well, by Elizabeth Hess.

Hess first came to the attention of the New York theatre world in the mid-eighties for her portrayal of actress Frances Farmer, in Sebastian Stuart’s incendiary play, The Frances Farmer Story. While the critics panned the play, and the fire department mysteriously closed it – at the time it was rumored to politically be too hot to handle – Hess’s “brave and powerful performance” was singled out by critic Clive Barnes as the evening’s saving grace.

Twenty five years later, with Broadway, Off-Broadway, regional theatre, TV and film added to her credits, Hess, still undeniably beautiful, has lost none of her talent to enthrall. Nor has the passage of years lessened her innate ability to channel, at the deepest level, as her performance is Dust To Dust reveals, the persona of each character that she inhabits.

Dust To Dust, less a play, more a performance piece, is not too far removed from the work of performance artist Karen Finley who like Hess has the uncanny ability to turn the makings of her words, as well as the workings of her mind and body – one minute she’s sane, the next crazed, one minute fully present, the next in another world – into an hallucinatory, roller coaster ride, not unlike watching a flickering strobe light.

As I watched Hess tear the up the stage, I couldn’t help thinking that, Dust To Dust, is also the mirror image (fraternal, as opposed to identical) of the last 30 minutes of Jez Butterworth’s play Jerusalem—the 30 minutes of muscular, over-the-top acting, and rolling around the stage, that all but gave Mark Rylance his 2nd Broadway Tony. Dust to Dust is also, in its quick, quirky, daring subject matter, and swiftly changing direction of each scene, second or third cousin to Rajiv Joseph’s Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo.

The play, if I may go back on my own words, opens simply with the stylishly dressed Hess in a black leather jacket, scarf, running shoes, and passport and boarding pass in hand, pulling a carry-on suitcase behind her. In the background, as Hess paces to and fro, airport flight announcements tell us that she is about to board a plane. Speaking in staccato-like cadences the visibly agitated Hess begins to chant words that reveal her inner thoughts which in turn trigger ours.

“Home, Home, Home. Want to go home,” she says. “No more time zones, heightened security, fear of Muslim insurgents, another attack, plastic baggies, pat downs, strip searches”, all thoughts, feelings, and experiences that we audience members could identify with. As Hess spreads her arms wide as if going through a security scanner, a loud male voice tells her to take off her clothes. But before we can digest the full meaning of these words, or for that matter the announcers intention, a loud click goes off, lights flash, traditional Bosnian music is heard, and the scene shifts dramatically. With her scarf going from around her shoulders to over her head and her rhythmically moving to Arabic music, Hess is now a Bosnian woman.

Again we get chanting. “Field of chamomile, fingering prayer beads, Alhamdulillah prayers, baklava, beating, beating, beating rugs, miritati dollies, American sneakers, dancing snowflakes, pita, nigella seeds, black market jeans, 24 karat hoops.” We are being given cultural clues, which when added up, telling us who this woman, where she lives, and the possible problems, when we think of history, as brought to us by the media, the problems she possibly might be facing.

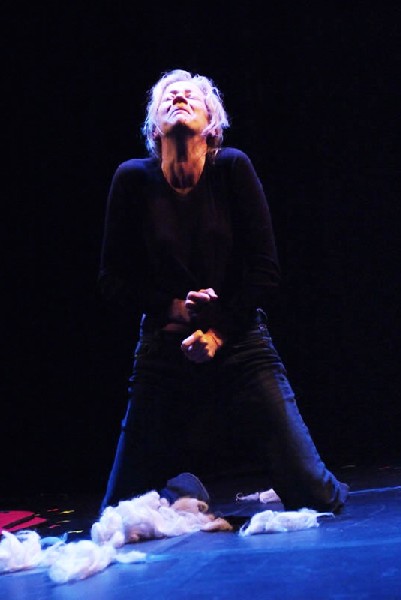

In scene three, Hess, whose play, according to the program “transforms the systematic rape of women in war-torn Bosnia into a silent cry played out on inner lives” – and it is all of that – begins to pull out all of her acting chops as her character, a Bosnian woman alone with her young 2 year old son, faces the onslaught of drunken soldiers intent on rape and murder. Again, using poetic utterances to set the scene, Hess breathlessly recites her dilemma in staccato rhythms. “Pounding, pounding, the door, my heart, my son and I, curled up, in the dark, after hiding, hiding from the enemy forces, who sweep by, like a pack of wild horses, turning everything over and over, before moving on, thank god, thank god” she says.

While the soldiers pass her house by – a temporary reprieve – in the following 16 smoothly flowing scenes, we watch as Hess’s Everywoman, bouncing from wall to wall, muscularly reenacts scenes of rape, murder, starvation, prisoner camp atrocities, and an early childhood molestation. The only escape from pain for these women, and perhaps for the audience as well, and this only for a moment, is when Hess’s characters, in order to escape their pain, return to their childhood where innocence reigned supreme, and safety was mostly a given. At this point they resort to remembering beloved childhood stories like Black Beauty and Pegasus.

Hess’s star turn commands the stage, but the music chosen by Technical Director Colleen Toole, which links, defines, and helps carrying each scene to the next, is also a starring player. Toole’s choices, from Classical, Jazz, Pop, and Bosnian music, all perfectly suited to the action of the scene are flawless. Particularly affecting is Toole's addition at the end of the play – an uplifting choice at that – of Rachmaninov's "Bogoroditse Devo", which translates to the "Ave Maria" (Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee). It allows Hess, who by now is visibly wet, worn, and spent, a relatively graceful exit, while offering the audience, many with tears in their eyes, a most welcome smidgen of hope.