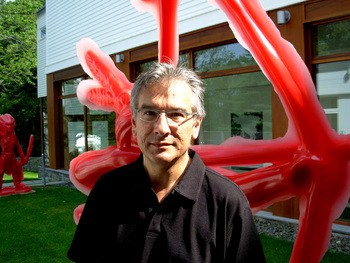

Aldrich Museum Curator Richard Klein

No Reservations Combined Native and Non Native Artists

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 21, 2013

Aldrich Curator Discusses No Reservations

Richard Klein Negotiates the Conundrum of Contemporary Native American Art

Reposted from Maverick Arts Magazine, September 22, 2006

How to quantify the degree of difficulty for a non native curator, Richard Klein of the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, to organize an exhibition “No Reservations” that uniquely conflates the work of five native and five non native artists in a project that makes an end run around the usual misconceptions about the First Americans? Although he conveyed an emotional aside during a meeting of several hours in the Ridgefield, Connecticut museum, of feeling “in over my head” on many levels he proved to be just the right combination of maturity, insight, heart and passion to take on a seemingly impossible task.

To convey the multi leveled complexity of his project let us quote an excerpt from the catalogue essay by the young Comanche writer, curator and critic, Paul Chaat Smith. I urge interested parties to read the entire essay when it is published in time for the October 15 opening and panel discussion in which the author will be a participant. So there is some risk of quoting out of context by not conveying his entire argument. But the following excerpt conveys some of the flavor of the issues facing non Natives willing to take on issues of indigenous culture. Smith’s essay and the catalogue are bound to be instant classics in Native Studies. And it indicates Klein’s risk taking to allow for this discourse under his watch knowing full well its uncanny boomerang aspect.

“…generally speaking, white people who are interested in Indians are not very bright. Generally speaking, white people who take an active interest in Indians, who travel to visit Indians and study Indians, who seek to help Indians, are even more not very bright. I theorize that in the case of White North Americans, the less interest they have about Indians the more it is likely one (and here I mean me or another Indian person) could have an intelligent conversation,” Smith writes.

“I further theorize that, generally speaking, smart white people realize early on, probably even as children, that the whole Indian thing is an exhausting, dangerous, and complicated snake pit of lies. And that the really smart ones somehow intuit that these lies are mysteriously and profoundly linked to the basic construction of the reality of daily life, now and into the foreseeable future. And without it ever quite being a conscious thought, these intelligent white people come to understand that there is no percentage, none, to considering the Indian question, and so the acceptable result is to, at least sub-consciously, acknowledge that everything they are likely to learn about Indians in school, from books and movies and television programs, from dialogue with Indians, from Indian art and stories, from museum exhibits about Indians, is probably going to be crap, so they should be avoided.

“…everything you learn teaches you that the Indian experience is a joke, a cartoon, a minor sideshow. The overwhelming message from schools, mass media, and conventional wisdom says that the Indians might be interesting, even profound, but never important. We are never allowed to be significant in explaining how the world ended up the way it did. In the final analysis, Indians are unimportant, and not a subject for serious people.”

Certainly this is a bleak and daunting message for anyone engaging issues of contemporary Native American art and culture. Why bother? He bluntly states issues and concerns that I have found to be daunting and discouraging. The voice and humorous rage of this provocative and intriguing young thinker appears to answer a tough question. Just who would step into the moccasins of the late Vine Deloria, Jr., the author of many books, an activist, provocateur, and Socratic bee on the hide of academics particularly anthropologists, archaeologists, sociologists and historians. His books are a must read for any “smart whites” venturing into the murky quagmire of contemporary Native culture.

There are times when taking on the issues that Smith’s essay skewers so ferociously and brilliantly reminds me of the maps of the era of exploration. In the Heart of Darkness of the interiors of unexplored continents there was the Latin phrase “Terra Incognita.” At the edges of oceans sailors were warned “Hic transit dracones.” Or here reside the dragons and sea monsters. Of course the allegory of this is that the greatest threat is ignorance and we have nothing to fear but fear itself. But there is also an embedded trope and conceit that Native culture is just another uncharted territory and that the scientist or culture worker can just get in there with the proper tools and resources and map it all into coherent theory and sense. That was precisely the folly that Deloria exposed. It changed academic thinking and methodology but it is a process that has been slow to catch up with culture workers and in particular the Byzantine art world, its material culture, commercialism and star system. The only valid critical measure in the art world appears to be how much the “product” is worth. Truth is that to date contemporary Native art is worth a pittance and is accordingly devalued by an indifferent mainstream of collectors, dealers, the media and curators. Other than the few delusional “smart” white people suffering cultural Mad Cow Disease, who gives a rats ass about contemporary Native art and culture beyond new age and Santa Fe kitsch?

Which is precisely why I wanted to talk with Richard Klein about taking on this important and fascinating project. After a tour of the exhibition in which he discussed individual works we settled into a staff kitchen where he prepared tea. I slammed away at him with my usual gonzo assault of provocative questions. But Klein had an outer layer of Teflon professionalism which aptly deflected my journalistic tricks and cheap shots. To paraphrase F. Scott Fitzgerald “Curators are different from us.” There were moments of deep penetration and valuable insight but I offer a report rather than an expose. The project itself was measure enough of his courage and risk taking. But, as always, I was far more interested in the why than the how.

There were several key elements that led to Klein initiating this landmark project of bringing a cutting edge Native project to a mainstream museum. He conveyed a life long interest in history particularly a concern for the local indigenous history of Connecticut, it’s initial genocide and recent recapitalization. As a contemporary curator, who travels extensively and has a finger on the pulse of the New York scene, he was aware of a critical mass of compelling emerging and mid career Native artists as well as a number of non Native artists dealing with aspects of the culture and history. It was the aftershocks of 9/11 that caused him to reflect on American identity and history. And he has a strong commitment to organize provocative contemporary shows that inform and create critical dialogue with the museum’s audience.

“I was always interested in the history of the North East and the early contact and stories of colonization in the first hundred years,” he said. “This was the honeymoon period. (Between native and European settlers).”

The change from general to specific interest occurred when “9/11 happened,” he said. “A couple of months later we were vacationing in Europe and I never felt more like an American. People constantly asked us what it felt like to be Americans. Most Americans don’t think much about being Americans. I’m not particularly patriotic. I’ve always felt like an outsider and yet I am an American. I have lived all of my life in the US and my world view is tempered by that background. Over the next year I thought about what makes an American an American. I kept coming back to the theme of one Hemisphere coming in contact with and overwhelming another Hemisphere. There is the issue of the cultural imperialism that America exerts on the rest of the world. I kept coming back to the story of dislocation and genocide of Natives that deeply defines America and its history.

“Simultaneously I was seeing work that touched on those ideas and this was played out against the success of the Pequots and Foxwoods which is the largest grossing casino in the Western Hemisphere. There is another tribe in Connecticut the Schaghticokes who have lived on a fifty acre reservation for the past 300 years. Their land abuts the Kent School. They were finally recognized as a tribe by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and then later there was a reversal of that decision when the BIA decided that they could not prove that they were a valid tribe.”

The struggles of the Schaghticokes were played out in the local media and fed into issues that were of particular relevance to the audience of the Aldrich. “The project developed when I saw interesting work and started to put two and two together,” he said. “I traveled to the West to New Mexico, Arizona, the North West, and California. I had a list of some 20 artists on the table. Those were directed trips (not fishing expeditions) as I had leads and knew who I wanted to see. There was a critical mass of material but I was not working on this project full time. As any curator of a small museum I was juggling a schedule of shows and other commitments. I had to look at available resources. The show could have easily been twice as big if I had more space. There is tons of material out there in various genres and sub genres.”

Given the range of material the project might have taken many different forms and directions. He talked about young Apaches making decorated skate boards near Phoenix and referred to performance artists but he pulled back from specifics. There were some established and mid career artists whom he briefly contacted but opted to focus on just five emerging Native artists. He did not want to be pinned down on artists he considered to avoid any speculation and embarrassment. But having done this project he anticipates other relevant artists will be brought to his attention although he has no immediate plans to follow up on those leads. Klein may well prove to be a contact person for other curators pursing projects but he insists on defining himself as a generalist and not an expert in this field of study.

Despite these disclaimers I wanted to know what it felt like to take on this project. Richard I wanted to know about your Feelings. “It was fun and challenging,” he said. “I felt at times that I was in way over my head. I met great people and had fascinating conversations but I was overwhelmed and there was nobody to help me. At first I wanted to work with a Native curator but eventually felt I could do it on my own.”

That lack of peer support seemed very relevant considering my own experiences and issues in pursuing this research. I asked him rhetorically that isn’t it just a matter of time before individuals and groups of emerging Native artists break out into the mainstream of the art world? Won’t that result in a feeding frenzy among potential colleagues? “That has already happened in Canada,” he said. “Rebecca Belmore represented Canada in the 2005 Venice Biennale and Brian Jungen is a rising art star.” Artists and curators I have talked with discuss how there is more support for and awareness of Native art and culture in Canada but that there are also other daunting issues. Also that Canadian interest and support does not reach across the border when American Natives look to expand their projects. So these are important issues to be explored at another time.

Having worked intensively since 2001 to bring this complex project to fruition and because of the intensive research and insight it entailed I asked Klein about his continued interest and commitment to the field. “I’m a populist,” he said. “I try to play to a naturally curious audience. For me the show is trying to say ‘hey, this is work that is complicated.’ White people, even those who are well educated, have the wrong ideas about Native art. Even here in Ridgefield there is a shop on the main street that is called ‘Taste of Sedona’ that is selling crystals and new age materials. Why is there a need for that and how does it survive? I’m concerned with the artists but I’m also interested in the public and shocking people into consciousness. I’m not promoting one particular kind of art or interest group. I’m shocking people into a greater consciousness.”

Once an exhibition is up on the wall and the catalogue has gone to press it’s time to think of the next show, and the one after that, what’s in the pipe line for the next season, and the one after that. As Klein expressed it there are those serendipitous occasions when personal interests and passions coincide with those of the institution which one serves. As a generalist curator for a small museum the mandate is to wrap up a project and move on. Fair enough. In the process, however, Klein’s exhibition and provocative catalogue will leave an indelible impact on “smart” pale faces who dare to take on the “snake pit” of contemporary Native art and culture.