Ric Haynes No Beer But Burgers

As the Crow Flies

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 21, 2013

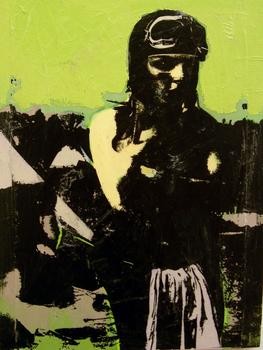

Ric Haynes

As the Crow Flies

In the studio are large, figurative, plywood cutouts, meant to be free standing that Ric Haynes is about to pack up and drive to the Bradley Academy of Visual Arts in York, Pennsylvania. An exhibition will be on view there from July 8 to August 26. For an artist who resides in Quincy, a suburb of Boston, that represents a lot of effort for a show in a remote location.

When I raised that point over lunch at a local restaurant, Ric, an old friend whom I hadn’t seen in a couple of years, seemed amused at my naiveté. “That’s what being an artist is about, Charles,” he replied in a familiar manner that is bemused, warm and a bit scolding. We had been down that path as peers and sparring partners, a couple of old bears, a number of times. But this time it seemed that we had aged and lost a step on the inside fastball. There were fewer brush backs and knock downs. But we were both wary of the ancient combat. Getting together to compare medals, stripes, and scars. It is why the Crow Indians who he hangs out with in trips to Montana affectionately call him Singed Wolf. The beat up one who counsels others and on the dangers of life.

“It is a great effort and expense to make the work,” he explained. “Then it is an effort to show it. The space is very beautiful. Artists strive to show their work in the best possible setting and circumstance. I am from York so there is a great incentive to have the work seen by that community. It says something to the art students that someone came out of York and went on to become a professional artist. Folks I went to kindergarten with will come to the opening. But the locals like to tell me that I am the second most important artist from York. Number one is Jeff Koons.”

We met during bus tours of Spain and Italy some years back organized by a Suffolk University professor, Alberto Mendez. Ric was sketching constantly and I got to tag along with him and his wife Lorraine at a couple of bull fights and a remarkable evening of flamenco. He was deeply knowledgeable of these unique Spanish traditions which I was experiencing for the first time. Actually, it had taken some effort to get Astrid to join me at the bullfight. She ended up rooting for the bull. Like Vegas, it proved to be a Once in a lifetime experience.

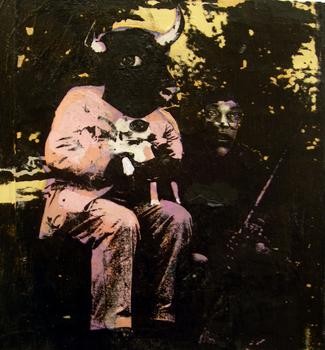

There is a smoldering passion in Ric that is richly evident in the imagery of the paintings, drawings and some 200 artist’s books he has produced. It involves complex imagery, iconography and a cast of fictional beasts, gods and monsters that would rival the Lord of the Rings. He is deeply involved with mythologies and cosmologies but without all the hocus pocus. He is far more humanist than New Age which is why I feel comfortable interacting with him and picking his brain for nuggets of rare insight.

When I first met him he was an expressive arts therapist and struggling with memories of Vietnam. It seemed attractive to share some of my own issues and demons for a bit of free advice. But one has either friend or therapist and not both in the same individual. Significantly, he left his therapy practice so it is easier to just be friends. It was amusing to find that the “therapy room” in the house, a place that I felt haunted by, has become the guest bedroom. I asked if visitors have strange dreams.

Several years ago he went back to graduate school to earn an MFA degree and concentrate on teaching art. He explained with some humor that he realized that his therapy clients were developing as better artists than he was. And that he was no longer intrigued by the study and treatment of illness. At least not in the usual Western sense. It was as a therapist, particularly the treatment of alcoholism, that he was first drawn to the Crow community in Montana. But he quickly backed out of that observing that they had their own therapies, such as the tradition of the sweat lodge, the sun dance and a number of other ceremonies and healing arts. This continues to involve and fascinate him.

When we met he had just returned from Montana. Less than a week. Again, I ask such dumb questions, why go through that effort and expense for such a short visit? The answer surprised me. “Because it is so emotionally intense,” he said.

It is this special relationship to the Crow, his personal psyche, and the wonderful mythology of the work that intrigues me. Particularly, now that I am making a commitment to work with contemporary Indian artists as a critic and curator. He explained that the Crow do not have the art traditions of other tribes but speaks of one remarkable friend and artist, Kennard Realbird. He described a magnificent, life size, bronze horse and rider, perfect in every detail that the artist gave to the tribe. But that Realbird declined to discuss it as “That would not make the work any better.” Perhaps that is the Indian version of the familiar artist’s statement “My work speaks for itself.” That if you have to explain it perhaps it isn’t that good.

This summer I am rereading “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee” by Dee Brown. All of our Suffolk freshmen are assigned this book which will be discussed as a part of a course I team teach, Integrated Studies. It is ground work for a visit and exhibition by the distinguished native artist, Jaune Quick to See Smith. So I am trying to get up to speed with Indian history and culture. A daunting and emotional process. My god, what a terrible legacy. So much blood on the hands of the American psyche. And so little dialogue. Staggering miscarriages of justice and broken promises, massacres, genocide, just swept under the rug. How to make of that contemporary art? What an incredible challenge.

Reading the history carefully the Crow do not come out well. They were the scouts for Custer in his war to exterminate their traditional enemy the Sioux. Working for the blue coats was the lesser of two evils. Ric added the detail that prior to the Battle of the Little Big Horn in which the 7th Cavalry was annihilated, Custer released the Crow scouts so they could steal Sioux horses during the engagement.

To the outsider and uninformed, which describes most Americans, all Indians are alike. It is only when you start to engage the history that you sort out ancient animosities and tribal differences. Only on the brink of extermination did tribal leaders try to rally ancient foes against a greater threat, Manifest Destiny. Brown states, chillingly, that during a two year interval in the 1870s some 2.5 million buffalo were slaughtered of which only 150,000 were killed by Indian hunters desperate for food and hides. Army officers routinely ordered the slaughter of vast herds of Indian ponies. There was a relentless and systematic policy of genocide. Driven primarily by the discovery of gold on sacred land like the Black Hills or for the fertile land of shrinking reservations coveted by white settlers. Waves of immigrants and spiking population fueled the rapid expansion into the West. Indians were simply slaughtered, based on fabricated threats, to create the state of Colorado. Perhaps the white soldiers were looking for weapons of mass destruction?

It is precisely this complexity that has drawn Haynes to the Crow. With some humor he speaks of a Crow friend who every day tells him the long list of enemies he hates. Because of the poorly drawn language of the Treaty of 1868 the US Government deeded over to the Sioux vast tracts of Crow land that had been occupied for more than a thousand years. The dispute exists to this day. This argument surfaces when the Crow stage an annual reenactment of the Battle of the Little Big Horn which represented a Sioux victory but on Crow land. The Sioux are invited to participate but decline and complain. So it goes on and on.

But Ric is clear in stating that, “I have my own culture as a descendent of Colonial settlers, the Pennsylvania Germans, Amish and Mennonites and deep roots in European culture,” he said. “The Indians say that I am like them but not quite. When I was in graduate school I came to focus on the sources of my iconography which are largely Mesoamerican.”

For the past seven years he has participated in the annual battle reenactment. The roles of white people are played by white people and there is considerable competition for the individual chosen to portray General Custer. The Crow always decide on the same man who actually is a “great guy and sport” and lives in Custer’s former home. Talk about role playing. The event is not about money raised although it attracts a large audience. After expenses there is little profit. He explains that it as a Crow attempt to educate people to history presented from their point of view. In August they stage the Crow Fair from a Thursday through Monday that attracts some 30,000 people including many other tribes who come and set up tepees organized by clan. It involves a rodeo and all kinds of dance and song.

At the time of Little Big Horn the Crow numbered about 2,000 people where the tribe today includes about 15,000 individuals. In 1885, the US Government intervened to end the traditional Sun Dance which in some versions, which vary from tribe to tribe, involves mutilations. The official policy of the Bureau of Indian Affairs was to repress native language, religion and culture. To “Americanize and Christianize” the Indians. The once banned sun dance was revised in the 1960s. Ric states that he has not participated in a sun dance “Because I am not an Indian.” He related how there are many deeply held secrets and protected traditions. “They show me what they want to,” he said. “You can observe some but not all of the ceremonies. They resent people who come in to do ‘research’ then write a book that gets it all wrong. I have been specifically asked not to write a book about my experiences.”

Even if invited to participate, he would decline because of a doctor’s advice. A sun dance entails four days of rigorous fasting and physical challenge. Traditionally, it was a test of the strength and courage of warriors.

Just why has he become so involved with the tribe? “I am able to be myself and accepted for who I am,” he says. “Also I like the sense of community and people working together. It takes several people to do a sweat lodge and about 50 people to enact a sun dance.”

There is a tendency to gloss over and glamorize Native American culture. To romanticize it as has been the case in the media and Hollywood. To focus on self appointed leaders like Russell Means and AIM whose motives are hardly pure or in the best interest of the diverse people he represents. To simply ignore the grinding poverty. The Crow reservation is the third poorest county in the state and eight poorest in the nation. The annual per capita income is $3,400. The tribe has high levels of alcoholism among adults. There are efforts to educate the youth and get them to college but those who do not have few prospects. A significant number who do get an education return to work as tribal leaders. There have been efforts to bring industries to the reservation, but, guess what, those plants closed and jobs were outsourced to third world nations with even cheaper labor.

In the face of such adversity, poverty, mismanagement, and federal neglect why cling to a tribal life? Why struggle to hold onto often barren land and eroding traditions of language and culture? They speak of “interruptions” such as Christianity or the media. Only the elders speak the pure language and dialects which are quickly disappearing. The kids want to speak like TV or hip hop not the old talk of the elders.

Given the generations of genocide, exploitation and abuse just how may white Americans constructively interact with our indigenous peoples and culture? What an incredible challenge.

For Ric the personal enrichment is clear and resonant. As a Singed Wolf he brings himself to others. And finds something through communal participation. And then reflects that experience in his life and art. Not that this is his only resource. He discussed the program of research and writing in graduate school. Exploring such topics as humor in art and a paper on morality. Of reading about Tantric traditions, medieval thinking, and philosophy, particularly Kant and Lancan. Or studying the images of the Zapotec people of Oaxaca Mexico. The resultant mythic creatures in his work that combine human and animal elements.

What then is so unique about his time with the Crow? “It is the only culture I know of,” he said. “That doesn’t require you to be anything other than yourself. I feel accepted.”