Uzbekistan: Part One

Tashkent and Samarkand

By: Zeren Earls - Sep 21, 2013

Uzbekistan had been on my short list of travel destinations for some time because of its legendary architecture and crafts. I welcomed the opportunity to join a tour organized by Lars Husby, a professional potter, who had been inspired by the exceptional quality of the Uzbek displays at the Santa Fe Folk Festival. Although August is not the ideal time to travel to Central Asia, known for its continental climate of hot summers and cold winters, I hoped the heat would be tolerable due to the lack of humidity; it was.

Our group of fourteen, mostly artisans from the Seattle area, met at Istanbul airport for the five-hour flight to Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan. Setting our watches one hour ahead, we arrived in Tashkent at 1:30 am. Clearing passport control and customs was a lengthy ordeal, where we had to account for everything we were bringing in — money, jewelry, electronics — on forms that were scanned, to be compared with ones filled out on departure to make sure we were not taking out more than we brought in. Finally we were met by Nazira, our Uzbek, Russian and English-speaking guide, who travelled with us through eleven of the twelve regions of the country during our twelve-day itinerary.

A one-day excursion in Tashkent began with the unique experience of money exchange, which is often handled through the black market. Two people in the group collected dollars from each of us and took them to a designated area, while the rest waited on the bus. They returned with bags full of sum, the Uzbek currency, worth some 2400 to the dollar. The money came only in 500 or 1000-sum notes, requiring dexterity in counting.

The Tashkent oasis lies within sight of the foothills of the western Tian Shan Mountains, whose melting waters feed the Syr Darya River. Turkic nomads came to the fertile valley to trade with early settlers in the 7th century and gave the city the name Tashkent, or “Stone City,” by the late 10th century, during Karakhanid rule. The city, which now has a population of 2.5 million, boasts imposing squares, wide leafy avenues, and monumental architecture, thanks to its recent socialist legacy. On burning summer days, spray from fountains throughout the city help cool off the dwellers of the mud-brick maze of the old town, still home to 150,000 Uzbeks, who have much in common culturally and linguistically with Turks living in Turkey.

Khast-Imam Square is the heart of the old town. The newly remodeled square sits behind the tall minarets of the new Hazreti Imam Jome Masjid (mosque). Nearby is the 16th-century Barak Khan Madrassah (seminary), founded by a descendent of Amir Temur (Tamerlane), who ruled Tashkent during the Shaybanid Dynasty. The courtyard features a rose garden surrounded by hujra (student cells), now workshops for traditional woodworking, embroidery, and jewelry.

A visit to a market near Chorsu offered the typical bazaar bustle. Named Eski Juva (“Old Tower”), after a nearby minaret marking a fortress, the bazaar is a labyrinth of covered stalls providing shade. Arrangements of dried fruit and nuts; baskets of fresh figs, grapes, and vegetables; and sacks of herbs and spices vied for attention, alongside heaps of cooked noodles and horse meat, black mulberry juice, round loaves of non (unleavened bread), and smoking shashlik (kebap). On the outside of the market, these wares spilled into brooms, puppets, clothing, slippers, skullcaps, carpets, and the like.

Along with the locals, we settled here for lunch, each ordering two skewers of shashlik served on a bed of sliced raw onions, non, and green tea. One person in our group spoke Uzbek and had visited Tashkent before. He explained the custom of the oldest at the table breaking off chunks of bread to serve others. The tea ritual called for the first bowl to be poured back into the pot to help the brewing; Uzbeks drink tea out of small bowls rather than cups or glasses.

The treat of the day was a visit to the ceramic workshop of Akbar Rakhimov. Set in a beautiful garden with flowers and fruit trees, the new building has been in operation for only seven years, as private family business was not allowed during the time of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic. The son, who interpreted for his father, was a third-generation potter himself. Here we were shown some of the oldest pottery styles, as well as beautiful vases, plates, and tiles hand-painted on the premises. Although I had promised myself not to collect any more crafts, I could not resist the temptation to purchase a vase.

The reasonably-priced Tarona Restaurant offered live music and folk dancing along with dinner. The cold appetizers included kidney beans and chicken salad with celery and cucumber, followed by vegetable soup and plov (rice), with lamb and spices as the main dish. After vanilla ice cream we called it a day, as we had a very early start the following morning.

Claiming our packaged breakfasts, we left the Samir Hotel for the train station. Traveling by speed train to Samarkand cut the bus ride from five hours down to two. Speeding along flat land until the foothills of the Pamir-Alai Mountains, we arrived in the Samarkand oasis, the fabled crossroads of the Silk Road. The outdoor temperature read 29°C.

The Maliki Hotel, our home for the next three nights, was within walking distance of the 15th- century Gur Emir Mausoleum, where a tour of the city’s architectural splendor began. A blue-tiled portal opens onto a courtyard of the resting place of the Turco-Mongolian leader Tamerlane, who made Samarkand the capital of his empire. The monumental mausoleum itself sits on an octagonal chamber with a turquoise fluted dome covered with glazed and patterned tiles, so that light and shade play on the mosaic hue. The interior is just as spectacular. Hexagonal onyx tiles lend the lower walls a greenish translucence, topped by Koranic inscriptions carved in marble. Seven marble cenotaphs encircle a dark green jade one for Tamerlane, matching the layout of the real graves in a vaulted crypt below.

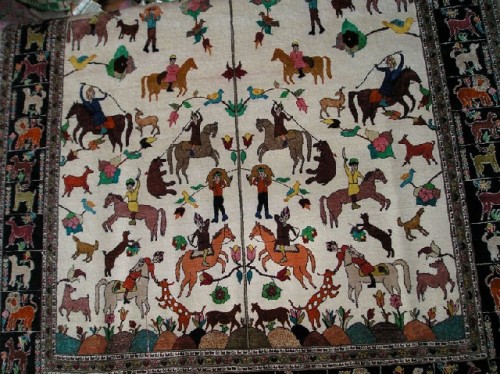

Lunch outdoors featured assorted grilled meat. For variety I ordered lule kebap (meat patties) on skewers, again served on a bed of sliced raw onions. Afterwards we visited a silk carpet workshop, which revealed the carpet-making process, from the use of natural dyes — brown from walnut shells, orange from pomegranates — to the skillful minute knotting of carpets, ensuring quality. On display were also suzane (embroidery) and ikat textiles, where the design predetermines the dying of the threads. My purchases here were an embroidered cap for my granddaughter Iris and an ikat cushion cover. Dinner introduced us to local specialties, such as cheese wrapped in thin slices of fried eggplant and golubtsi, or stuffed cabbage leaves. Moonlight behind the mausoleum was a fabulous sight.

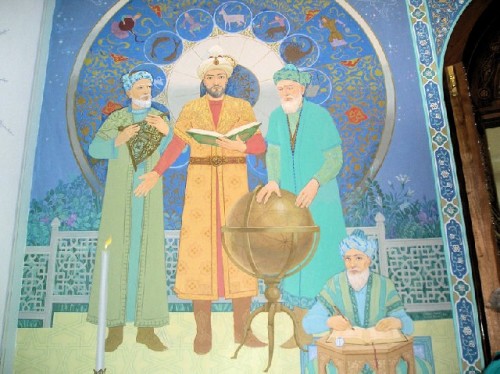

The next day’s learning and discovery began at the observatory of Tamerlane’s grandson, astronomer-king Ulug Beg. The 15th-century building, destroyed by fanatics after the king’s death, was discovered by Russian archaeologist Vyatkin, who found the remains of a structure in the form of a huge cylinder 46 meters across and 30 meters high. Underground he found a giant instrument designed to measure the movement of the sun, the moon, and other celestial bodies. Deeply embedded in the rock to lessen seismic disturbance, the arc is now covered by a portal and vault at the center of the observatory’s foundations. Initiated by Uzbek President Islam Karimov, a new memorial museum in the shape of an enormous medieval clock, details the diverse facets of the careers of Tamerlane and Ulug Beg.

Shah-I-Zinda, an ensemble of mausoleums, is a holy site for pilgrimage associated with the Prophet Muhammad’s cousin Kusam-ibn-Abbas, who spread Islam to Central Asia in the late 7th century together with the first Arabian conquerors. Meaning “the living king,” the name refers to Kusam, who by legend ascended to heaven alive, after hiding in a well here to escape his attackers. Since then the site has been sacred, obliging every governor to construct a public building or bury relatives along the ancient street, which consists of lower, middle, and upper courtyards. Architectural masterpieces date from the 11th to the early 20th century.

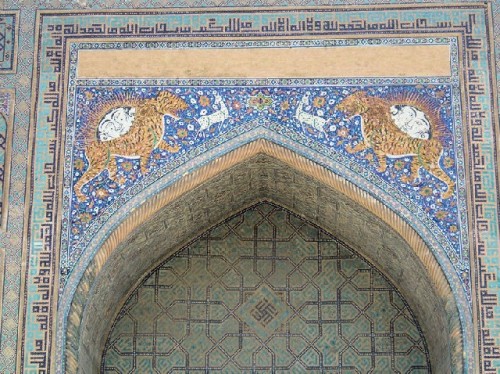

Following lunch of another Uzbek specialty, manti (dumplings) filled with meat or vegetables, we continued on to Samarkand’s magnificent Registan Square. The square has been restored to its original splendor of architectural and decorative wealth, with an ensemble of buildings whose mosaic detail radiates with the changing light. The main trading center during Tamerlane’s time, Registan Square is today flanked by three Madrassahs — Ulug Beg, Shir-Dor, and Tillya-Kari — dating from the early 15th to the 17th century. Many of the student cells have now become gift shops.

Each seminary has a huge arched portal with unique facades, ranging from geometric patterns on Ulug Beg to a stylized representation of animal life on the “lion-bearing” seminary Shir-Dor to solar symbols and gold leaf on the “gilded” seminary Tillya Kari. Due to the upcoming Mustaquillik Bayram (Independence Day) celebration, preparations were underway at Registan Square, with access to the buildings regrettably limited by scaffolding for lights and sound systems.

A visit to Hunarmand Handicraft Center, in addition to a gallery, offered a full range of textile art, from clothing and jewelry on mannequins to contemporary designs using traditional fabrics. A silk ikat vest, a felt flower ring, and a clay toy whistle were my purchases here, at very reasonable prices.

Our third and final day in Samarkand began with a visit to the Bibi Khanum Mosque and Mausoleum, named after Tamerlane’s senior wife. This was the main mosque of the Temurid period, paying tribute to the conqueror’s power in its scale and artistry. The mosque soars over an arch with flanking minarets, leading to a rectangular court paved with marble hauled from India on elephant back. All of Central Asia is on a fault line and tremors have taken a heavy toll on the old buildings. Although repaired in recent years, huge cracks have appeared in the domes and the brick walls are crumbling.

In the shadow of Bibi Khanum lies the Siyob Bazaar, Samarkand’s major farmer’s market. Cutting through the bustle of people, we walked by artfully arranged dried apricots stuffed with walnuts and roundels of non bread, which comes in 20 varieties with individual patterns and names.

Aiesha is the studio of Valentina Romanenko, a designer from Ukraine. She designs contemporary clothing, using fabrics dyed by her son. Seamstresses, working at home, realize her fashions, which are sold at the shop, where I bought a long quilted scarf with pockets. Attractive young models put on a fashion show for us. Afterwards we visited the premises; every corner of the house inside and out reflected the designer’s creative touch.

Once again, the choice for lunch was plov rice, this time with yellow carrots, chick peas, and lamb. Pickled tomatoes with dill and vinegar helped reduce the fatty taste as we ate by the spoonful. Another walk around Registan Square led us to an art gallery, where I purchased an ink drawing of the square depicting its earlier days as a trading center.

As a break from our meat-based diet, Nazira suggested we try a fish restaurant for our final dinner in Samarkand. Much to our surprise, a real fish, hanging as a sign-post, identified the Balik (“Fish”) restaurant. Fried carp and pickled tomatoes constituted our evening meal, as we refrained from eating raw vegetables during the trip.

Looking forward to our adventure south to the next legendary city of Bukhara, we ended the Samarkand chapter with a final viewing of the full moon behind the Gur-Emir Mausoleum.

(To be continued)