Boston Artist Arthur Polonsky

At Childs Gallery

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 23, 2025

|

|

|

Obituary by Charles Giuliano

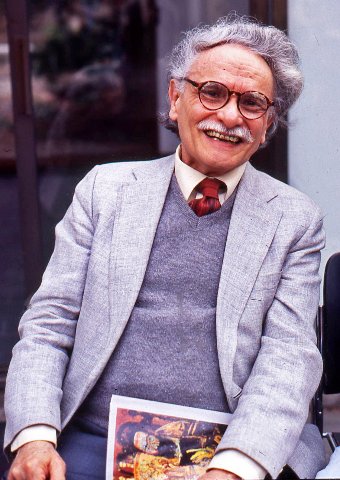

With the passing of Arthur Polonsky (June 6, 1925 - April 4, 2019) the last link to the greatest generation of Boston artists has been broken. They are known and somewhat misrepresented as The Boston Expressionists.

Of which Arthur, my professor, mentor and friend was a member of the second generation. The founders comprised the Eastern European, Jewish immigrants; Jack Levine and Hyman Bloom, rightly thought of in tandem, and the German born, Karl Zerbe. Together they were a daunting triumvirate that left a legacy of figuration upon generations of graduates of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and The School of Fine Arts at Boston University.

Like his mentors Polonsky was the son of Eastern European immigrants.

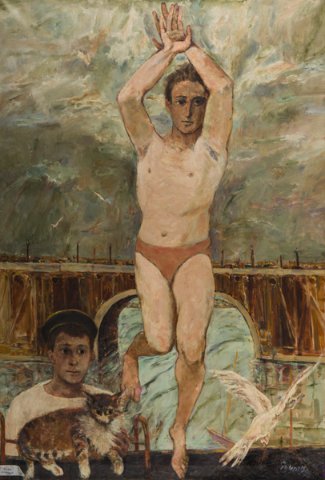

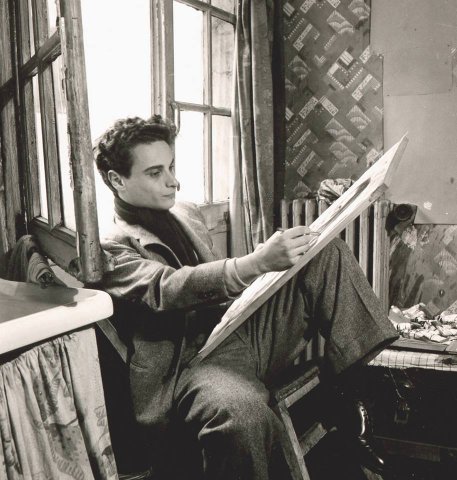

At the Museum School he was a student of Zerbe. He won a traveling fellowship and from 1948, as Stuart Davis put it, “He breathed Paris air.” That widened his reach from the somewhat mordant Boston version of expressionism. We find in his work no rotting corpses or corrupt politicians. There is no hint of the Judaica that informs aspects of the oeuvre of Bloom and Levine.

From 1950 to 1960, Polonsky taught at the Boston Museum School in the Painting Department. In 1954 he became Assistant Professor at Brandeis University in the Fine Arts Department, where he remained until 1965. Polonsky was Associate Professor at Boston University, College of Fine Arts, from 1965 to 1990.

Sources from Boston and Paris amalgamated into works of lyrical fantasy with Rosetti- like evocations of ethereal women as muse. He was always admired as a great draughtsman of his generation. Arthur could draw like Raphael. While paying homage to Picasso and Matisse, the twin towers of School of Paris, he passed through them to the angst and edge of Kokoschka or the visual vocabulary of Paul Klee.

It was the latter’s “Pedagogical Sketchbook” that he drew upon as an approach to teaching studio classes that inspired my freshman year at Brandeis. With him I studied foundation design and drawing.

Because Boston Latin School viewed art as frivolous I attended Saturday morning classes at Mass College of Art. It was mandated by my doctor parents that I would enroll in pre med. Chemistry, which I flunked, proved to be the end of that. That freshman year I earned an A from Arthur which confirmed a commitment to become a fine arts major. That led to a fist fight with my father.

It is to Arthur than I owe a life in the arts. His classes were so absorbing that there was no going back. Fortunately, the world was spared a very bad doctor.

His design lectures were whimsical performances with many dramatic pauses, gestures and asides. He would make a mark then step back, verbalize his deliberations, then make another mark. In tantalizing increments eventually a form would emerge. We came to understand the many stutter step deliberations that comprise creating a composition. I read Klee’s slim book and tried to decipher its succinct process of checks and balances.

In that sense, if you look long and hard at Klee, it becomes apparent that each work, amazing in its diversity, documents a visual conundrum. An image may be viewed as a problem and how it is solved.

Once Polonsky’s lesson had been delivered we were set to work. Often that was too daunting. It was more enticing to sit with and chat/ torment my teacher. With affection and a bit of tease I called him “Pops.” It was impossible to antagonize him. With masterful Tai Chi he deflected the awkward thrusts of a grasshopper.

An elaborately tended to pipe was artifact and intriguing fetish object. When pointed at me to fend off a verbal assault it was a curious weapon. Arthur was a wizard and I was intent on learning the secrets of his magical world of art. While never rebuffed or discouraged, in these exchanges, he challenged and encouraged me to find my own way. There was deft craft in the manner that he controlled and shaped my sanguine rebellion. He never provided answers to my anxious barrage. Questions were countered with questions. It was a verbal, aesthetic chess game.

Not surprisingly he was adored by students. It was not uncommon to see him in the cafeteria holding court. That was hardly his intent but a result that caused envy and some hostility from other faculty.

Other professors provided answers to my questions. Compared to Polonsky’s challenge of self discovery they offered didactic instruction. One took a brush to my paintings and another’s tool improved my clay sculpture. I learned to make art in their style and technique. Arthur encouraged me to think for myself.

Eventually, I took up media and approaches that had nothing to do with what I had learned in school. Identifying and solving aesthetic problems was consistent with the independent thinking I learned from Polonsky. Another primary mentor was Creighton Gilbert who taught Renaissance art history. He taught me how to think about art.

During the golden years of Boston Expressionism, from the 1950 to 1964, Polonky was represent by the seminal Boris Mirski Gallery. Researching this article I learned that he had been an activist and a founder of the Boston Arts Festival (1952-1964). They were wonderful annual events that I enjoyed as a teenager. The grass roots effort came as a protest against the indifference of the Museum of Fine Arts and Institute of Contemporary Arts.

Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose.

The MFA is planning a long overdue show of Bloom. Last week during an interview with MFA director, Matthew Teitelbaum, I asked when the museum will begin adequately to celebrate past and present Boston artists? It is best to remind artists that the squeaky wheel gets the grease.

Other museums have done a better job. Under former director, Katherine French, the Danforth Museum has collected and shown the Boston Expressionists and figurative artists. In 1990 there was a Polonsky retrospective at the Fitchburg Art Museum. Under Sinclair Hitchings he had five exhibitions at the Boston Public Library from 1969 to 1999. Hitchings formed a notable collection of prints, drawings and photographs by Boston Artists. When it was a fine arts museum The Fuller Museum of Art had major shows of Bloom and Henry Schwarz. The traditional Childs Gallery in Boston is taking an interest in expressionist artists. We dropped by this week to see a selection of paintings by Arnold Trachtman.

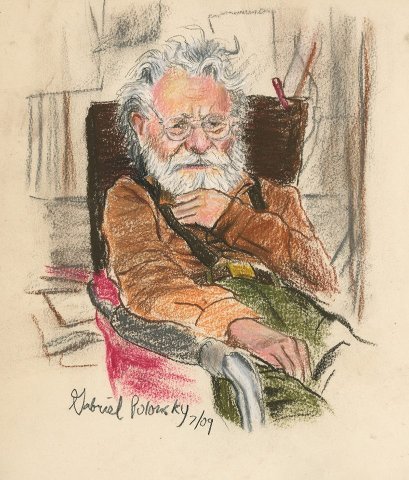

Polonsky is the subject of a documentary feature film called Release from Reason which is currently in production by his son, Emmy-nominated director Gabriel Polonsky. Arthur was married to artist Lois Tarlow from 1953 to 1983, who survives him. He is also survived by his three sons Eli, D.L., and Gabriel.

References:

"Arthur Polonsky". Kantar Fine Arts - Arthur Polonsky. Sep 23, 2018.

Brown, Robert (Sep 23, 2018). "Oral History Interview" Smithsonian Archives of American Art.

Steiner, Raymond J. (Sep 23, 2018). "Artists Equity Associaton a Look Back". Art Times: A Literary Journal and Resource for All the Arts.

Bitely, Jessica (Sep 23, 2018). "Boston Arts Festival Records " (PDF). City of Boston Archives and Records Management Division: Guide to the Boston Arts Festival records.

"Harvard Art Museums". Harvard Art Museums. Sep 22, 2018.

All of the information in "Early Expressionist Meetings" is based on the "Oral history interview with Arthur Polonsky, 1972 Apr. 12-May 21," conducted by Robert Brown for the Smithsonian's Archives of American Art. (See also Endnote 2.)

"Arthur Polonsky" Boston University, College of Fine Arts. Sep 23, 2018.