14 Stations by Robert Wilson

Passionm Play from Oberammergau to Mass MoCA

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 24, 2013

Mass MoCA's American Premiere of Robert Wilson’s

Passion Play Installation, 14 Stations

On view through October, 2002

While technicians feverishly labored on last minute details, Robert Wilson, during a somewhat rambling and theatrical introduction for an afternoon member’s preview that stretched out over an hour before visitors got to see the work itself, admitted that he was, "stalling for time."

Somewhat later, Joe Thompson, director of the enormous, sprawling complex of buildings in North Adams, that comprise the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, dressed in work clothes, explained to the audience that, "I usually come to these occasions more suitably attired. But we have been working round the clock, not me necessarily, but a crew has been putting in sixteen hour days for the past couple of weeks to get this up and running. There are too many people to thank them all individually, but as many as 35 people have worked on this project. While Robert Wilson thinks large in big broad concepts, he also pays particular attention to the most minute details."

Some five years ago, Wilson explained, he had been approached by the mayor of Oberammergau, a community of 5,000 that has been presenting a Passion Play, every ten years, since 1634. Initially, Wilson, who stated that he follows no specific organized religion, turned down the offer. When he did eventually pursue the ambitious project, the citizens of the German village, in turn, rejected his concept as inappropriate for the traditional fourteen signifiers, or Stations of the Cross, that tell the story of the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

"I tended to agree with them," Wilson said somewhat shockingly, "But I then attempted to persuade them that they were wrong." When they eventually understood his stark, graphic, theatrical, conceptual overview, they became actively involved in actually fabricating certain sculptural aspects of the work. In a rather remarkable manner members of the once skeptical village became participants and believers in this truly magnificent project.

On many levels, artistic, conceptual and purely visual, it is by far the most unique, ambitious and successful project so far undertaken by the relatively young museum. This installation goes a long way toward closing the gap between a vast and fascinating architectural container, and works that live up to the magnificent surroundings. So far, the building complex has been a more spectacular draw than the works on view. All that changes with this must see project that fills the largest gallery; a two story high space, that is larger than a football field.

Along a central axis are a series of small sheds, each containing a room, viewed through an end window, in which there is sculpture, dramatic lighting, sound, light and painted background. The first station, that contains no shed, is actually a double wide, transcept with a sound "well" and hanging bare bulb lights that evoke Christian Boltanski. This represents, "Jesus is Sentenced to Death." At the far end of the "nave" is "Resurrection" which comprises an apse of bound, arched saplings forming a niche that contains a suspended, upside down figure hovering over a cot-like, bare bed.

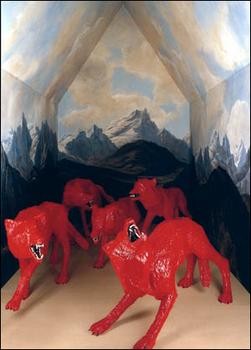

Devout Catholics, who have grown up with the Stations of the Cross in their parish church, will undoubtedly identify with some of the themes of the sheds. They range from quite specific, a sprawling figure in Station 9, that represents, "Jesus Falls Under the Cross the Third Time," to rather abstract, for example, the snarling, teeth gnashing, red wolves, of Station 12, "Jesus Dies on the Cross." Or, an abstract, suspended rock, for Station Two, "Jesus Takes the Cross on His Shoulders."

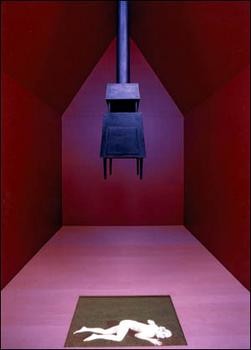

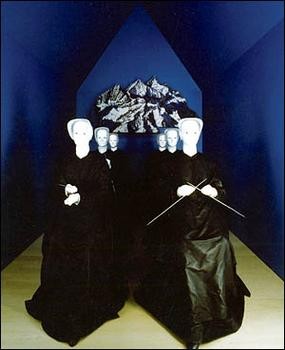

Given the proximity of North Adams to Hancock, just a short drive away, there are many ironic references to Shaker traditions. These comprise the very sheds themselves. And, in Station 8, "Jesus Meets the Weeping Women," several life sized, seated women, knitting rather than weeping, are dressed as 19th century Shaker devotees. There is another specific reference in Station 7, Jesus Falls Under the Cross for the Second Time, which consists of a suspended Shaker wood stove. Visitors to the Hancock Shaker Village will readily recognize this uniquely designed object.

The work was first presented at Oberammergau, outdoors, in 2000, as the 40th consecutive Passion Play, on a grassy meadow outside the Passionspielhaus. The Boston based Goethe Institute was a contributor to bringing the work to North Adams.

Although the work is rooted in traditional Christian iconography, Wilson has given the text the broadest possible humanistic interpretation. It appeals to and resonates with viewers of all faiths and levels of belief. And, although it was a work in progress over the past several years, it takes on new layers of insight and significance in the post 9/11 zeitgeist. It is precisely the kind of work that evokes the deepest and most poignant responses to loss, suffering, passion and martyrdom. Indeed, it is the frail vulnerability and humanity of Christ that is seen here rather than His Divinity. It is that aspect of the work that is broadest and most universal for viewers of every persuasion.

"I am particularly pleased that there are children here today," Wilson said, "As I want the work to be simple enough to be understandable and appealing to them as well."

Having followed the enigma that is Robert Wilson over the years, this strikes me as among his most successful projects. His theater pieces in particular have been especially challenging and not always popular with audiences.

During a spectacular, gala dinner with artists, museum directors, installers, donors, critics and friends, seated around an enormous set of four tables comprising a candle lit cross, I got to tell the artist that I had, "Survived," the three plus hour, CIVIL warS: a tree is best measured when it is down. I was among the quarter of the house still seated and offering tepid applause during its run at the American Repertory Theater in Cambridge, Mass. At ART, I also had occasion to see the Juniper Bush, with music by Phillip Glass, as well as, Knee Plays. And, in another setting, The Photographer.

I asked how he was viewed in the theater world and if he had plans to return to ART with any productions. There was a knowing, but rather warm smile in response to my tale of "surviving" CIVIL warS. He exchanged a kind of, "here we go again," exchange of looks with his partner who was standing next to us.

By way of explanation he discussed how he had been the only nominee for Pulitzer Prize in Theater for that production in 1986. "It was the only time that a nominee was not awarded the Pulitzer Prize, because those who approve the committee nomination decided that it ‘wasn’t theater.’"

Picking up on that, I suggested, with some humor, that a "script and text might have helped." Depending upon who you talk to, his experiments in theater have been both loved and despised. Artists, particularly multi media practioners, have been fascinated, while the traditional theater crowd maintains that he is more or less out to destroy the theater. I have heard both arguments advanced with equal passion.

Until now, my responses to his work as a visual artist have been mixed. I didn’t care for the Museum of Fine Arts, 1991 exhibition which, at the time, I dismissed as, "Prop Art." But the Armani installation at the Guggenheim was simply spectacular. Not that I give a fig for all that couture, but what he did with the space was truly amazing. I asked him about that project.

"I had done the installation for the 20th anniversary show of Armani, so I was invited to do this installation," he said. "It was a very tough project. After all it is Frank Lloyd Wright you are dealing with. Most people who install in that space like to take advantage of the views and vistas, how you can look across the space on multiple levels. I chose not to do that."

Instead, Wilson brilliantly surrounded the outer spiral of the enormous ramp with a running white scrim. This created a vast sloping runway and a sense of closure that created a set of patterns of subtle colors and exquisite fabrics. You were moved to see it as a whole, as art, as installation, as sculpture, and not just as "fashion."

He commented how he had recently installed that traveling exhibition at Guggenheim Bilbao in Spain. "Gehry is also tough. I have now worked with spaces designed by the two most difficult and challenging architects; Wright and Gehry."

Compared to that, Mass MoCA was a piece of cake.

Reposted from Maverick Arts Magazine, December 13, 2001