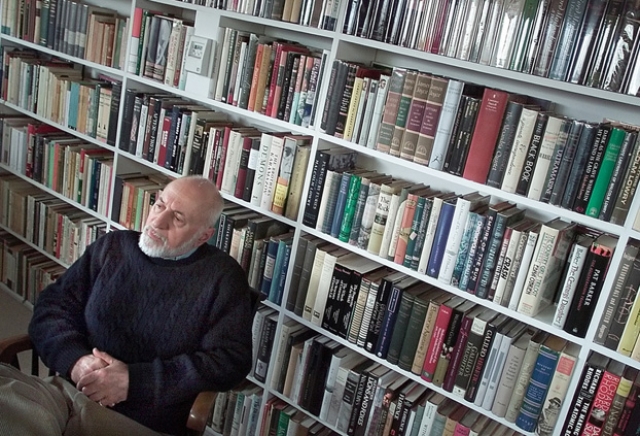

Gloucester Author Peter Anastas

Responding to Olson's Place as the Geography of Our Being

By: Karl Young and Peter Anastas - Sep 24, 2016

Growing up on Cape Ann in the hamlet of Annisquam, and then later as a graduate student in American Art and Architecture, I was aware of the rich history of the visual arts in Gloucester from Fitz Henry Lane to Winslow Homer, Stuart Davis, Marsden Hartley, Edward Hopper, John Sloan, Paul Manship and Folly Cove Designers.

Relatively recent involvement in writing and publishing three books of poetry, with another in progress, induced probing into family history and Irish ancestors the Nugents and Fynns of Rockport.

A consequence of this activity has been probing into the rich literary and historical context of Cape Ann. The monument to be dealt with has been Charles Olson and his epic The Maximus Poems.

There has been a compelling urge to dig into Olson and the influence he had as the epicenter of a generation, ongoing, of other writers, musicians and poets.

A major recource is Gloucester writer and activist Peter Anastas.

We met briefly in April when researching source materials. He was cataloguing in the library of the Cape Ann Museum. Later he attended my reading while in residence at the Gloucester Writers Center.

Corresponding I suggested that we might conduct an on line interview.

He sent me a massive, 34,000 word interview he conducted with Karl Lane with permission to use it as I saw fit.

We are reposting a 5,000 word excerpt.

There is the understandable risk of taking this excerpt out of context but it does address issues and concerns that are relevant to the pursuit of Olson and how he has impacted the work of Anastas and others of the Gloucester literary circle.

Because of the global significance of Olson, Gloucester, the polis of his Maximus poems became not just the locus of his literary concerns but also a destination and inspiration for the many distinguished authors and poets that found their way to his home.

Editor, Charles Giuliano

Karl Young What has been the influence of Charles Olson on your life and work?

Peter Anastas There are certain people in our lives, writers we have read or people we have encountered or known personally, who have, in a sense, given us the world, opened us to ways of looking at the world or understanding our own lives in ways that might never have been possible if we had never met them. Charles Olson was one such person for me, both in terms of our friendship and through his writings.

Olson helped me to understand what it meant for someone like me to have been born and grown up in a singular American place like Gloucester, Massachusetts. He had the ability to peel back the layers of time in a locale, a neighborhood, a single house even, a patch of forest, a moraine landscape, to reveal the depths and dimensions of its history. Olson helped me see that Gloucester was not simply the oldest fishing port in America and, as such, an archetypal place of human activity. He also helped me see that Gloucester was a continually evolving ecosphere, and that an understanding of the rich and complex ecology of my home town and the woods and fields that surrounded it led to an understanding of the natural history, geography and ecology of the larger world.

With respect to writing itself, the most important lesson I learned from Olson was that writers, be they poets or prose writers, should pay attention to what he called "the literal" as against "the literary." By this Olson meant that one need not embellish what one encountered in the world. One need only describe it with exactitude for maximum effect, or as Williams put it, "No ideas but in things."

Olson also encouraged me to study the history of my own town, my region and, indeed, the nation itself, as he had, through the primary documents. Court papers, land transactions in probate, property line surveys, wills and testaments and Quarterly Court records of civil litigation were, for Olson, the ur-texts of history, and as significant as the land itself for reading the passage of human habitation in given places. Maps told him more than narrative histories, though when it came to the narrative he said he found more significance in town histories, written by local historians, than in the dominant works of academic history.

His theory of "saturation," — that you concentrated on one place, one writer, one topic until you had absolutely exhausted it for yourself and therefore prepared yourself henceforth to take on any subject — has proved to be immensely helpful to me in approaching not only the study of individual writers but also of larger topics in literature or history.

Most of all, Olson showed me how to be myself, how to ferret out what lay deep inside me. And he did this by his own example of courage and struggle and by giving me permission to be myself in the way that parents aren't able to do for their children, who often need a mentor to show them the path to further growth and development. Olson modeled the life in art I had always wanted to live. He demonstrated by living in a book-filled $28-dollar-a-month cold-water walkup on Gloucester's waterfront that one did not need to have material wealth in order to pursue the life of the mind. Olson counterposed himself and his ideas against the consumerist culture that was growing around us ("in the midst of plenty/walk/as close to/bare"), noting once, in the pages of the Gloucester Daily Times, "One has to have the strength of a goat, and ultimately smell as bad, to live in the immediate progress of this country."

Finally, it was Olson's activism against Urban Renewal (he called it "Renewal by destruction"), against the loss of Gloucester's historic architecture, against the filling of wetlands and all the "erosions of place," as he called them, that inspired my own activism on behalf of the fishing industry, the preservation of Dogtown Common and against overdevelopment and gentrification. For in the end, my activism and that of those I've worked closely with for over forty years, is about the preservation of place, not only as an idea or ideal but as a real, living, breathing community...

KY What role has your birth and residence in Gloucester, Massachusetts played in your life and work?

PA Thoreau said that he had "traveled a good deal in Concord," and I might say the same for myself in Gloucester. Though I have also traveled in Europe and the United States, in many respects Gloucester has been my world, the place I know the most about, the source of practically everything I have written.

KY Didn't Henry James call Thoreau "worse than provincial — he was parochial?"

PA As an internationalist James had to escape the localism that so much of American literature was saturated in during the 19th century-a localism and a regionalism that emerged as Americans broke away from England and Europe both intellectually and culturally in order to embrace their own history and identity. Thoreau was in the forefront of this movement of self-declaration, when town histories began to be written and local historical associations were formed. It was only natural that American writers began to write about where they lived.

KY Is that why Thoreau has meant so much to you?

PA We read selections from Walden in high school during sophomore English with our teacher, Miss Claudia Perry, who was a Radcliffe graduate and an inspiring Americanist. But I wasn't ready then for Thoreau's understanding of the natural world, his practical Transcendentalism, though I had been fascinated by his descriptions of living through the seasons at Walden Pond when I came across his writings while browsing in the library years before high school. By high school I was immersed in the novels of Steinbeck and Hemingway, and when I wasn't reading fiction I was listening to jazz or trying to play it. When I entered college, Walden, was part of the required reading in English 1. Our instructor Steve Minot, who was himself a writer, helped us to appreciate the precision of Thoreau's prose, rooted as it was in the phenomenal world, just as Thoreau had immersed himself in the history of Concord and New England. Since then Walden has been a key text for me. Every year I read a few pages or a chapter from it. I might add that writing my master's thesis on Thoreau's concept of place also helped me to understand the nature of place itself-historically, culturally, politically and symbolically-and my own birthplace as one of the first American places.

KY There must have been some other attraction for you in this strange man who lived mostly in the same house with his parents when he wasn't traveling in the Maine woods or Cape Cod.

PA I loved Thoreau's eccentricity, but I also admired his politics. I was writing my thesis in the mid-1960s at the height of the Civil Rights Movement and the opposition to the war in Vietnam. "Civil Disobedience," "Slavery in Massachusetts," "Life without Principle," and "The Last Days of John Brown," were essays that electrified me, showing me a side of Thoreau that I hadn't recognized before. Reading those incendiary tracts was an important part of my own radicalization. Who could have guessed that the quiet hermit of Walden Pond had once declared, "I need not say what match I would touch, what system endeavor to blow up"? After reading that, who needed Abby Hoffman or H. "Rap" Brown?

Aside from Thoreau's bracing anarchism and his Abolitionist politics (I've come to understand Transcendentalism as the single, great, native intellectual and political movement in America), Thoreau was a loner. As I've said, I've been a solitary, too, all my life, from the days when I wandered the riverbanks of my neighborhood collecting butterflies and studying the weeds and wildflowers to the hours I spend by myself today walking, reading or writing in my journals.

KY Was it a difficult transition from Thoreau's localism to that of Charles Olson's in The Maximus Poems?

PA Actually, it was Olson who led me back to Thoreau. Not personally, because Thoreau wasn't a great favorite of Olson's-he once wrote on a postcard to Gerrit Lansing, "Thoreau is not thorough" — but in terms of Olson's focus on the multi-dimensionality of place. I began reading The Maximus Poems seriously in 1962, when I returned from Italy to Gloucester. I was also seeing Olson and his wife Betty almost daily. His deep study of local history and the way he explored the past and present life of Gloucester in the poems helped me to realize that it was possible to write about the place one came from in a way that didn't merely evoke "nostalgia" or "local color." Gloucester, her streets and people and the extraordinary quality of the natural environment, came alive in Olson's poems and in the letters he was writing to the Editor of the Gloucester Times slamming development that threatened to destroy the city's historic buildings and valuable wetlands.

When Olson wrote in his powerful, "Scream to the Editor," "Oh city of mediocrity and cheap ambition, destroying its own shoulders, its own back greedy present persons stood upon," he wasn't romanticizing the nation's oldest seaport, as many writers and painters had done before him; he was warning the community about what it would be losing in its rush to make a Faustian pact with Urban Renewal. The local came alive with Olson, both in his poetry and his activism, so I had a living example in him of what Thoreau had been writing and enacting in Concord in the 1840s and '50s.

When I went to graduate school, one of the first courses I took was Wisner Payne Kinne's seminar on Thoreau. As soon as I started reading A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, I began to view Thoreau through an Olsonian lens, and I was on my way to a study of the significance of place that led to my thesis on Thoreau's approach to it. Conversely, reading Thoreau helped me to understand Olson more deeply, though they were very different writers. This concentration on place-what it means, how to know it, how to live in it knowledgeably and write about it lovingly-became the focus of my work. It also helped me to understand why I had returned to Gloucester.

KY What does place mean to you?

PA Place is not only where we live, but also where we get our bearings from. Place is who we are and how we feel about ourselves, how we're anchored in the world. Place is our very identity, "the geography of our being," as Charles Olson put it. And if we lose place, or undermine its character, whittle it away year by year by inappropriate development — chopping up neighborhoods, driving people away from the houses they were born or grew up in — we destroy the basis of our lives, if not our very identities.

Place is topography, the look and feel of the land, the mapping of streets in a town, the complex of neighborhoods, what has been built by humans or has evolved from nature. A sense of place also includes the history of where we live — who inhabited it before we did and how they impressed themselves and their culture on the land. Place includes our personal and collective history as we live daily in a given place. Place is the life forms we cohabit with, indeed all the biota of our environment.

Place is also symbol and myth, for a single town or city, the history of its founding and growth, as Thoreau believed, can be viewed as an archetype for the origin and evolution of all places on the earth.

- Y. Agnon wrote that "Every writer needs to have a city of his own, a river of his own, and streets of his own." As it is for writers, so it is also for everyone.

KY Presumably there was some more practical reason for why you chose to return to your birthplace and remain there.

PA In order to stay out of the draft I had to find a teaching job. Fortunately, there was one ready to hand in Rockport, MA, the town with which Gloucester shares the island of Cape Ann. My brother Tom, who'd been stationed in the Pacific during his service in the army, came home after being discharged in January of 1963 to warn me that we were preparing for war in Vietnam. "It's going to be hell," he said, "and you should do everything you can to stay out of it." I lost my educational deferment when I decided not to pursue the fellowship in Italian I'd won at Berkeley in 1960 and had delayed for two years while still in Florence; so all that remained was teaching, which offered an occupational deferment. Having already taught English for two years in Florence to finance my stay, I discovered that I loved helping others to learn, so it seemed natural to continue in the US, first in Rockport to fill a vacancy and then permanently in Winchester, MA, where I was subsequently hired to teach English and literature. At that point, living in Gloucester, first with my parents, and then on my own while commuting to Winchester, was a practical decision.

But there were other reasons why I chose to remain in Gloucester. I found there was an incredible community of writers and artists around Olson. There was my old friend and mentor from my early teens, the poet Vincent Ferrini, who had lived in Gloucester since 1948. Through Olson and Ferrini I met Jonathan Bayliss, a Harvard and Berkeley educated business analyst and writer, who become a friend, confidante, and intellectual inspiration. Stimulated by Jonathan's work on ritual and dramatic poetry, I returned to the study of the Greeks I'd begun in college, and that fascination with ancient history and culture continues. I also met the poet and scholar Gerrit Lansing, who had important ties to the New York School, and whose studies in Jung and the occult opened me to other ways of looking at the world. Gerrit is also the best read person I've ever known, making him an invaluable resource. Among local visual artists, there were painters like Mary Shore and Celia Eldridge, and later Thorpe Feidt, whose diversely experimental work helped me to continue an interest in contemporary painting that began when I was growing up on Rocky Neck.

Olson was continually being visited by writers like Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan, Ed Dorn, Leroi Jones/Amiri Baraka, Diane DiPrima, Michael McClure, Robert Kelly, Joel Oppenheimer, and Allen Ginsberg. Even Jack Kerouac showed up once at his back door. I met the avant-garde filmmaker Stan Brakhage in Olson's kitchen and had a chance to see several of his groundbreaking works at Mary Shore's during Brakhage's visit. There were scholars and archaeologists who came to Gloucester to pay their respects to Olson, along with the curious and the adulatory. An evening at Olson's could entail impassioned talk about everything from John F. Kennedy, whom Olson had taught at Harvard, to Joyce, whom Olson didn't like, or Dostoevsky and D. H. Lawrence, both of whom Olson adored. And Olson often read to us from his poems in progress about Gloucester or his brilliantly speculative essays, many of which were published in Human Universe.

"Why go to Berkeley when there's graduate school right here at my kitchen table?" the poet once remarked. And I knew he was right.

Meanwhile, living in Gloucester, first in our family house on Rocky Neck, then nearby in my own waterfront studio at the Beacon Marine Basin, I came to appreciate the intrinsic beauty of my native place. As America's earliest art colony, Rocky Neck was a miniature Provincetown. Painters like John Sloan, Edward Hopper and Marsden Hartley had lived and worked here. And in my day, the European-born painter Albert Alcalay, in whose studio I'd met Olson during the summer of 1959, was a powerful presence. Albert and his wife Vera had met and married in Rome just after the war, and they introduced me to contemporary Italian painting and writing. They also encouraged me to speak Italian, which I'd just begun to study in college.

After living in Europe, Gloucester seemed more to me like an Italian or French Riviera town than the run-down resort I'd tried to escape from. Everyone had a garden, and in the morning light the houses of Portuguese Hill glowed from the water like villas clinging to the hills of Liguria. You could hear Italian or Portuguese spoken on the streets and buy fresh bread and pastries in the shops, along with homemade pasta and sausages.

If, when I was in high school or college, anyone had predicted that I would return to my home town and remain there for the rest of my life, I would have been incredulous. It was fully my intention to live elsewhere in the US, in Berkeley, for example, where I'd once had fantasies of teaching, or in Europe, as I'd been inspired to do by my readings in Joyce, Lawrence, Pound or Hemingway. But when I came home to find the rich intellectual and artistic life inspired in part by Olson's presence (though there had always been writers and artists on Cape Ann) and the natural beauty I took for granted when younger, I found it hard to let go of. My brother was living in Manhattan and that seemed exciting; but I had no real connection to the city, or any chance of a job without getting drafted.

KY Are you sure there wasn't something else that kept you in Gloucester beyond the lure of place?

PA I've since wondered if it wasn't also fear that rooted me here, fear of having to establish myself somewhere I wasn't known or didn't have friends or family, fear of failing or of loneliness. But I seem to have settled easily in Florence, and before that in Brunswick, Maine during my college years, so fear seemed less the case, though for a good part of my early life I suffered from separation anxiety. I've wondered, also, if I didn't have some abnormal emotional attachment to my birthplace or my family, an attachment I feared breaking. Gloucester has been experienced by many natives as nearly impossible to leave-we call it the "island mentality." Once people succeed in getting away, they often rush back or never feel fully at home in any other place. There are even some residents who boast that they've "never crossed the Cut Bridge," which was once the only way out of town. I've yet to explore these issues fully, but I hope to in future work.

KY If there was so much stimulation and intellectual company in Gloucester, why did you return to graduate school?

PA Again, it was Olson who encouraged me. Not directly. He never said, "It's time now for you to return to your studies." It was more the consequence of two years of dialogue with Olson about American literature, American history. Aside from a course in contemporary literature at Bowdoin, in which we'd read the major novels of Hemingway, Faulkner, and Fitzgerald, and a seminar for English majors where I encountered Farrell's Studs Lonigan, and Dos Passos' USA for the first time, I had read very little native writing. I'd read Moby-Dick in high school and then again on my own in Italy after reading Olson's seminal Call Me Ishmael, on the mythic and Shakespearean sources of the novel; and, of course, some Hawthorne, which we were all required to read in high school. But I had no real sense of the continuum of our literature, no feel for its history until I began discussing it with Charles.

One day he suggested that I take a look at the "Custom House" preface to The Scarlet Letter. "American literature really begins with that essay," Olson said. I rushed over to the Sawyer Free Library and signed the book out. I remember that it was the 8th of May in 1963 and the whole town was fogged in. I sat reading near the French doors of my studio, barely able to see the harbor below. I couldn't take my eyes off Hawthorne's text as I went on to read the novel, which I hadn't opened since high school, when I couldn't possibly have understood it.

As soon as I'd finished reading The Scarlet Letter I knew what I wanted to do. I would study American literature. Immediately, I began making applications to graduate school. I expected it would keep me out of the draft. I also hoped to gain some experience teaching at the college level. Tufts awarded me a three-year renewable teaching fellowship in English, allowing me enough money to live on after tuition remission, so that I could pursue both the MA and PhD degrees.

KY Why didn't you complete the doctorate and begin a teaching career?

PA After three years in graduate school in the US and a couple in Italy, it was clear to me that I was not interested in scholarship purely for its own sake. I loved the detective work it entailed, but I didn't have the desire to devote my life to academic pursuits. I discovered that I really wanted to write fiction, and I worried that teaching and scholarship might undermine the imaginative work I yearned to do. I had seen too many classmates and friends, who also wanted to write, fall into what I felt at the time might be a trap, teaching with little time for one's own work. Olson had left Harvard before receiving the doctorate, and his remark in a letter to Bob Creeley that it was "difficult to be both a poet and an historian," came home to me.

KY What about the draft?

PA By the time I left graduate school in 1967 I was thirty years old and our son Jonathan was two, so I'd effectively avoided the draft. I'd also enhanced my knowledge of English literature by studying Renaissance drama and Milton's poetry and prose with Michael Fixler, who was one of the best teachers I ever had. And on my own I'd steeped myself in English and American Puritan theology and writing in an attempt to understand the basis of the American mind.

KY Have you ever regretted not completing work for the PhD?

PA I have. But my solace is that I did complete a very rigorous master's thesis, which one of my advisors called the equivalent of a doctoral dissertation. This showed me that I could do scholarly work and that I'd at least mastered its techniques, which I could employ on my own. But in my heart I knew I didn't want to spend the rest of my life in the academic world. The backbiting I'd witnessed at Tufts, the competition for grants and honors, the professional jealousies, were not for me. Tough as survival in Gloucester often seemed-drugs, drinking and violence, the ups and downs of the fishing industry, the battles we entered time and again to stop deleterious development-life in my hometown seemed a lot realer than life on a college campus. I felt that if I were going to write seriously I had to be in an environment that fostered writing itself, not writing about writing. I've never looked back.

KY Why do you read and why do you think others read?

I couldn't imagine my life without a book. Since childhood I have read for pleasure, for transport, for the pure delight of getting lost in a story, perhaps a tale of adventure that might take place in a far off country, or in a part of my own country or region, which I enter inter willingly and often breathlessly in the pages of a book. I read to learn about other people and places, about things I know nothing about — particle physics, plate tectonics, Medieval painting. I love to immerse myself in biography, in the stories of the lives of writers, artists, scientists, politicians. Reading biography allows me to learn not only about the people whose lives interest me, but about the times they lived in, the art or craft they practice. Stories of coming of age, of self-discovery fascinate me because we are ever coming of age and finding ourselves, or new facets of ourselves. And I read poetry to immerse myself in the consciousness of another artist, to see other angles of vision on the world, or to enter into the meditative space of a thoughtful person.

I also read to write, as Olson wrote, quoting Melville. I'm inspired to put words down by practically everything I read. If I'm writing fiction, I like to read fiction; likewise, non-fiction. Reading primes the pump for me. It also teaches me how to write, how to approach a particular scene I want to create or a topic I'd like to address. I'll often ask myself, "How would Flaubert describe this encounter?" or "How would Sven Birkerts lead me through this exercise in criticism?"

From early childhood I've loved to sit in a corner by myself and read for hours, lost in words, in images, in the struggles of others. As I grew older I read to learn, as I'm doing just now in reading Orlando Figes' The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia, one of the most incredible accounts of survival (or non-survival) in a totalitarian society I've read. While I'm reading Figes at night, at odd moments during the day I'm also reading Roberto Bolano's 2666, a stunning novel that helps me to understand what some of my contemporaries are writing and how they are writing. It's nothing for me to have several books going at the same time. While I'm reading Figes and Bolano I'm also reading a couple of critical studies about Hemingway's lifelong fascination with cross-gender behavior. I read TLS each week, The London Review, the New York Review, the New Yorker and dozens of national and international newspapers and magazines online. But only a book satisfies my deepest need to read.

As to why others read, I would say that they are captivated by narrative as I am. Though fewer people are said to be buying literary fiction today, the rise of book clubs is a healthy sign that reading isn't dead. Literary books clubs bring people together to read and discuss demanding texts. It was by a friend who belongs to a local book club that I was inspired to begin reading Bolano, whom I'd long known about but hadn't got around to reading. Others get their books online by downloading or reading them on a Kindle. Young people are reading the Harry Potter books the way an earlier generation read Tolkein or we read Jules Verne.

To be sure TV and the digital technologies are cutting into the world of books and printed texts, but so did radio and movies for my generation. An immersion in the immediate gratifications of the visual and the digital may inhibit a young person when it comes to the book, undermining the habit of print: but I know a young woman with only a high school education who works as a cashier in my local fruit and vegetable market. She's always reading — good books, too — The Alienist, by Caleb Carr, Tolstoy — and she loves to talk about books, recommending them to customers, eagerly asking others what they are reading. And when I go to the public library I'm always running into people who are either returning or taking out literally stacks of books at a time — and not just mysteries and self-help texts. Many are reading substantial fiction and non-fiction. So I wouldn't write the book off yet, or those who love to read. It's possible that fewer people read poetry — I read it less these days than I did when I was younger; but when books like Jack Spicer's My Vocabulary Did This to Me or Jack Hirschman's Arcanes come to hand, as they recently have, I realize how important poetry is to me and I immerse myself in it with the same fervor and excitement that I read Pound and Williams as an undergraduate.

Yes, the society has been dumbed down by the inanities of TV sit-coms and reality shows, by leaders who lack critical intelligence, by school systems that teach to achievements tests rather than challenging kids to think, read and write for themselves, as I was by my teachers. And trade publishers are tied to the bottom line and the demands of their accounting departments as never before. Their editors seek novelty rather than books that stretch the mind; and if a serious writer isn't making them any money he or she is dropped from their lists. These are hard times for writers, and, by extension, for readers as the flow of good new books is inhibited. A society that doesn't support its best writers and artists, its libraries, is a society in decline.

Not too long ago my local public library junked its card catalogue, which contained records, many of them hand-written, on individual books going back to the 19th century. That paved the way for what the library director called the "weeding" of the collection. This weeding entailed de-accessioning more than half of the collection. Aside from certain "classics," approved by the Library Association for retention in public libraries, books that had not been signed out for five years were tossed directly into a dumpster; others were put on sale at "a buck a bag," including a first edition of The Autobiography of William Butler Yeats and the novels of Wright Morris, also in first editions. When I reproached the director for depriving the citizens of Gloucester of their literary heritage, his response was, "I'm not running an archive." He's gone now, but so are most of the books I grew up on, including Zimmer' Philosophies of India. This has been happening all over the country, so that the public library, once the central place of education for working people, indeed for all Americans who weren't affiliated with colleges or universities, is now a shadow of its former glory, and again, we end up dumbed down further and deprived of our freedom of inquiry.