Jonas Dovydenas Endless War

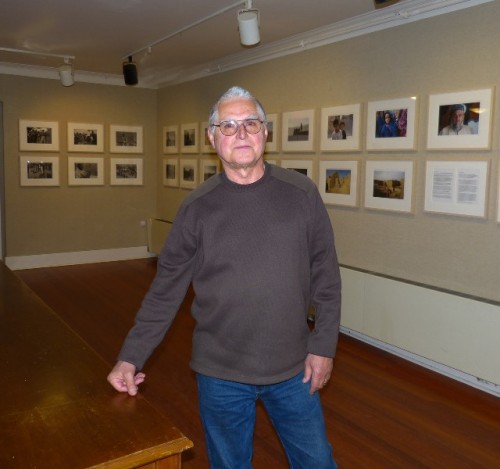

Afghan Photo Series at Lenox Library

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 26, 2014

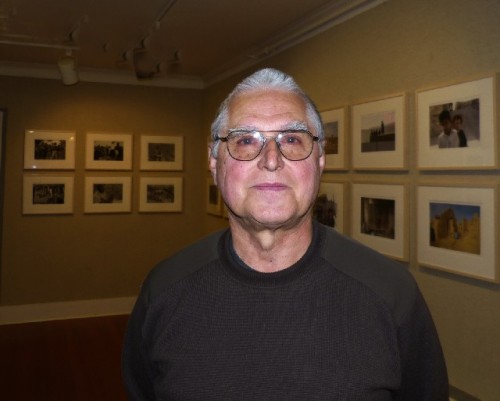

From 1985 until fairly recently the Berkshire based photograher Jonas Dovydenas made a number of trips to Afghanistan. He stared by shooting black and white film and later abandoned the darkroom switching to digital cameras. In all he shot some 15,000 frames. These were culled and edited resulting in the recent exhibition at the Lenox Public Library. He had previously shown his Nevada series there and is now at work organizing a show of his early Chicago series. Currently he is inolved with recording the seasons and studies of nature.

Formally trained by the renowned photographers Harry Callahan at RISD and Aaron Siskind in Chicago he approached Afghanistan from the perspective of a fine arts photograher. Unlike photo journalists he did not work under deadline for an editor. He insists that there was no preconceived mandate or point of view that drew him repeatedly to a war zone. Initally he had a personal incentive to see the Russians have "Their ass kicked."

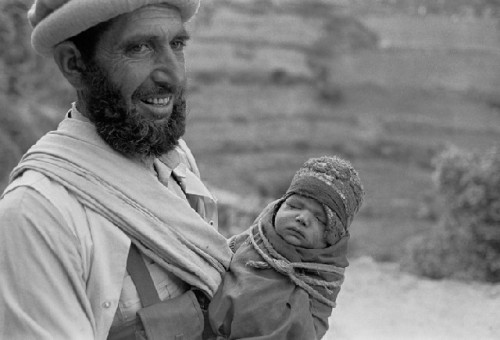

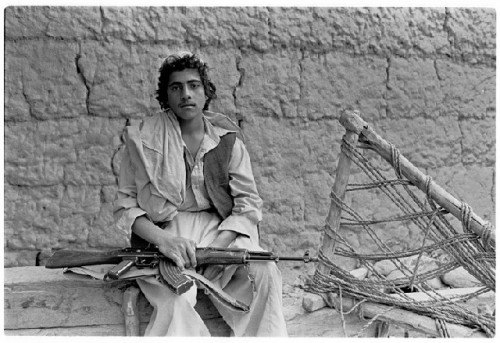

In the exhibition which starts in black and white and rotates chronoligically ending in recent landscapes there are no captions. He wants viewers to derive their own responses to the images. He was delighted when I suggested that this story follow that idea by a slide show with no captions. You are invited to just scroll through them and draw your own conclusions.

In addition to exhibitions Jonas hopes to develop the work as a book project. It would have a particular appeal to the military who served in Afghanistan.

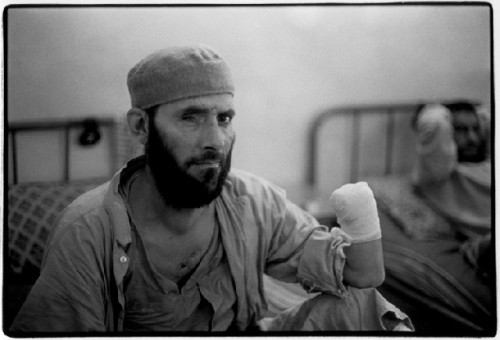

This is a body of work that I have viewed in development over several years. I often asked why he kept returning. After every shoot there was a certain depression about missing something. That was an incentive to return. Most recently he focused on the American military and in particular the medical divisions. He described highly successful teams of surgeons from Texas who really enjoyed their tours as part of National Guard units. They got to focus on their work with top notch medical facilities and no distractions.

He speaks of the unique camaraderie of soldiers for whom active duty represents the best years of their lives. Not having served that is far apart from my own social and political views. In a familiar take on liberal and conservative differences he stated that I was anti military. That's far from the truth. The issues are so complex that they are beyond easy definition or understanding. But I also reject his argument of just shooting what he sees as a kind of statement of fine arts formalism.

I argue that just by opting to shoot in a war zone places him within the definitions of a "concerned artist." For which there is a great tradition from Pierre visiting the battle field as an "intellectual" in War and Peace to Goya's series the Disasters of War or those of Otto Dix. The counter argument is that we see no carnage in the images of Dovydenas. More often we encounter village life, children playing before the camera, or groups of Afghan and American soldiers.

We are about the same age born just months apart. He in war torn Europe and I in America. We have very different but vivid memories. Mine entail keeping scrap books cut and pasted from Life Magazine or the Movietone News during weekly visits to the cinema. His include sitting through Allied bombing of Germany huddled in a bunker where his mother clutched his hand and remained calm. His parents refused to show fear. It's a part of the toughness that persists in his persona.

Evoking Citizen Kane on his deathbed I suggest that there is Rosebud in all of us. There is no such thing as objectivity in art. When he lifted his camera to shoot those 15,000 times the act and visual decisions were based on every aspect of his prior life experience. It informs every thought we have, dream, word we speak and move we make on the rocky road of life.

Charles Giuliano We have just viewed your exhibition at the Lenox Public Library Photographs from an Endless War. (Taken from an image of a tattooed message on the back of a soldier's neck.) It’s a beautiful space and the show, in two parallel rows, is densely hung. When I asked how many you counted them. We were surprised that there are 88 images. That’s a lot of work. Over what period of time did this come about?

Jonas Dovydenas It began in 1985 when I went to Afghanistan twice in May and October. I returned in 1990 when there was a switch over with the Americans just leaving. The Taliban hadn’t popped out yet but it was being hatched by the Pakistanis. I saw Arabs then lots of them in 1990. I assume most of them were Saudis. They were like combat tourists. They wore fancy clothes compared to the Afghanis who wore pajamas made of baggy polyester and cotton. These guys came in wearing more tropical stuff.

CG Were they in combat

JD Some of them were but I didn’t see any combat myself.

I was in a village with a group of kids in their teens to twenties. One of these guys came up to them and wanted to take them up on a roof and show them how to pray to Mecca. The kids are looking at me and rolling their eyes. Who is this guy?

Turns out they had to treat him well because he was rich and there helping them. The Afghans do not like Islam in particular. They follow Islam but their own traditions even more. For them tradition is sacrosanct. Islam is something that they laugh at for some of its rules.

CG What traditions do they follow?

JD It’s the tribes and families doing things according to tradition. I don’t think there’s anything in Islam that dictates that the oldest son must marry before the next oldest gets to marry. That’s more important to them. There are lots of jokes about Imams. If you can’t do anything else in life you become an Imam.

CG When viewing the exhibition I was surprised that some images of children looked quite Caucasian. You commented on the ethnicity of Afghans.

JD There are three groups. The Pashtuns are Caucasians. They can be light haired or dark haired. The next group are Tajiks. They are from the North East and are more Asiatic. They have Mongol and Chinese features. You can immediately tell who they are. Another group the smallest one are the Hazaras.

(HazÄra are a Persian-speaking people who mainly live in central Afghanistan. They are overwhelmingly Twelver Shia Muslims. They represent about 9% of the total population. More than 650,000 Hazara may be found living in neighboring Pakistan and an estimated one million in Iran.)

They conbsider themselves the descendants of Gengis Khan (c. 1162 – August 18, 1227. Born Temüjin, he was the founder and Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, which became the largest contiguous empire in history after his demise. He came to power by uniting many of the nomadic tribes of northeast Asia.)

They were the ones in the valley where the Buddhists were and where the statues were blown up by the Taliban. That was in Hazara country. They are discriminated against. They are more liberal in their religion. They are more educated. They have higher economic positions in the cities and in the countryside.

CG How do these groups get along?

JD They don’t. They stay away from each other. They were fighting against the Russians. When they got rid of the Russians they were fighting among themselves. They destroyed Kabul. It was Afghans bombing each other.

CG So who are the Taliban?

JD They are mostly Pashtuns. They were kids brought up in schools organized by the Pakistani intelligence service. It’s like a virus was introduced into Afghanistan. It was a brilliant move of propaganda and agitation. It’s a political movement which had taken over Afghanistan once. Now they are trying to do it again. Who knows what’s going to happen. Pakistan has always tried to interfere with Afghanistan. Part of that is because half of the Pashtuns are on the Pakistan side of the border. That’s way in the hills where borders make no difference whatsoever.

When Zia was president of Pakistan he was quite frank is saying “We want to keep the pot stirred in Afghanistan.” To what end I don’t know. Do they want to take over the country? I don’t think they can.

CG What’s the value of Afghanistan?

JD It’s a country of 28 million people. There’s a middle class of educated people. There’s a lot of wealth. Nobody knows how much wealth there is in Afghanistan. Gems, minerals, one of the largest copper mines.

CG Doesn’t that say something about us for defending freedom in countries with natural resources. While ignoring genocide in countries with few resources of interest to us.

JD I don’t know what value Afghanistan is to America. I don’t think we’re getting anything out of it. We’ve been putting money into it right from the beginning when we were competing with the Soviets. It’s a part of the world that’s strategically important if you want to look at it that way.

All we’ve done is gone in their clumsily and spent a ton of money. They corrupted us and we corrupted them. If you open a hydrant to get a cup of water everything gushes out. All those armored vehicles which we left behind or scrapped were made in America. That money went into somebody’s pocket. The workers in Detroit.

I don’t buy that America is always poking around where there’s something tangible. Oil? Maybe. Everyone’s after oil.

CG Describe you military background.

JD I left high school and wanted to do something. I didn’t get into college and I’ve forgotten why. So I checked out the Air Force. I signed up for the navigator school. I tested in the top 2% of everything and they just loved it. Once I got into training I realized the military life was not for me. I ended my enlistment instead of continuing with officer training. I spent three years in the Air Force going through air to air missile school. They kept me back to teach electronics. I spent three years in Denver.

It was great. I went to see the second gig by the Smothers Brothers. They were just stand up comics in a bar. Judy Collins was singing in cafes. That was the culture in the early 1960s.

CG You have an affinity with the military. What motivated you to go to Afghanistan?

JD I was born six months before WWII in Lithuania. The Russians came. The Germans came. We left. My life has been determined by war. My family went to Germany during WWII as refugees. We survived. It was luck.

My father was in line to get tickets to Dresden. There was a shorter line with tickets to Bavaria. That’s how we ended up in the American zone in Bavaria. It was two weeks to a month before Dresden was obliterated. Had we ended up there we would have been among the 180,000 who died.

War is part of my life. I remember where I was when the Korean war started. I know where I was when WWII ended. I was with some kids when another kid ran up and said the war is over. We were in a refugee camp. I was in college when Vietnam started.

CG Where were you in college?

JD I went to Brown. I applied to Chicago but they looked at my grades and said we don’t think we can take a chance with you. I had the same interview at Brown and they enrolled me. Back then you actually talked with the director of admissions. It was the same conversation I had in Chicago but with a different result. I was an English major but became a photographer because I can look better than I can write. I took courses at RISD with Harry Callahan.

He wasn’t an influence on my style but he was an influence as an authority in terms of what he had accomplished. He would flip through photographs and say “Everyone takes a shot of this but it’s pretty good.”

Then I went to Chicago and took a course with Aaron Siskind. He was just the opposite. He would pick up photographs and tear them apart. Even though I have nothing to do with the way he worked but he was a wonderful teacher. With Harry Callahan you learned by osmosis with Siskind it was all a wonderful critique.

I photograph what’s interesting to me and what’s in front of me. It’s a matter of picking something and sticking to it for a long time. I was photographing in Nevada in 1966. I kept coming back to it. Fifteen years later I decided I should do something with this. I looked at it and it wasn’t complete so I went back. That was another show that took more than ten years to make. I photographed in Chicago where I lived. Now I will try to put a show of that material together.

CG What was your motive in Afghanistan? Did you have to be embedded or did you make your own way there?

JD In 1985 I didn’t need anything other than just show up. Frankly I wanted to go there and see the Russians getting their ass kicked. It wasn’t so much the Russians. It was the communists.

CG What have you got against the communists?

JD They did some bad things to my family. It was personal. My father was kind of a liberal. When the Russians came in he wasn’t going to flee to the woods and join the partisans. He was kind of a wait and see guy. They came in and lo and behold they needed a Parliament. A week before the elections they announced who the candidates would be. My father was one of them which was a total surprise to him.

In a year and a half that we was in Parliament he figured it all out and knew all the big shots who were running the show. He published a book on it. Of course once that happened, if the Russians came back, he couldn’t stay. He was an enemy of the people. We packed up and left. So I’m not a friend of the communists.

CG What was the motive to be in Afghanistan?

JD I wanted to see how the Russians were dealing with it. Afghanistan is the size of Texas. Lithuania is flat. No mountains just hills. The Lithuanians have resisted the Soviets for years. Right now there are fewer Russians in Lithuania than Latvia or Estonia. Because it was a dangerous place for Russian bureaucrats. Plus some other reasons we don’t have to go into. The administrators out in the boonies would be killed. So Lithuania ended up with fewer Russians and what there are have been assimilated. There isn’t this core of Russians like in Latvia who stick together.

CG Have you been back to Lithuania?

JD I go back there all the time. I go there a couple of times each year. In 1936 my father won a prize for the best novel of the year. I thought I would revive that tradition. I founded a prize which is awarded by the writer’s association. They judge the books and all I do is fund it. There is an award for the best novel of the year so I go back for that.

CG Do you read the novels?

JD Yeah, I do. I read some of them. I’m totally bilingual in fact English is my second language.

This year Betsy and I and friends went back as tourists. We hired a guide and translator. Betsy did not want to talk Lithuanian. It was pretty nice. There are no Michelin restaurants there but the food is pretty good. Vilnius is one of the best preserved cities in Europe. There is Gothic and pre Gothic architecture. The city is largely 19th century.

When I came back from Soviet trips (to Afghanistan) I didn’t do much with it. I showed them (images) around. After 9/11 I got interested again. I went back this time embedded with Americans.

CG The first times you were on our own.

JD Yes in the sense that I made contact with groups that take you in. I didn’t just go in by myself. I guess there are people doing that today but they risk having their head cut off. When I was embedded I would arrive and spend two or three weeks on my own in Kabul. With people that I knew. There was an Afghan American Institute which had a guest house where I stayed. Back before the Taliban you could do that as Kabul was totally safe. You could go anywhere and photograph.

Then, when I was embedded, I went to the villages with National Guard people. I drove around with a medical unit. We announced that we were coming. People would show up with all of their ailments.

In our convoy a vehicle was blown up by a roadside bomb. I wanted to get out and photograph it. They wouldn't let me warning that there might be snipers.

We bombed the hell out of the Taliban. They were considered a nation and we removed that nation. We helped to create a new Afghanistan. The last time the U.S. did that without controversy was when we put Japan on its feet. It was totally benevolent and it worked. That also happened in Germany. It was just the opposite of what happened after WWI. We gave the Germans a chance to rebuild. It was successful.

In Afghanistan we weren’t nimble enough politically. It was a culture we didn’t understand.

For my last two trips I really focused on the American soldiers and Medivac units. They were surgical groups from the National Guard in Texas.

CG We come from very different social and political positions. You have a different point of view about the American military. To what extent does that inform this project? Is there an agenda and narrative to this work?

JP We are poles apart Charles. The extremes are north and south and we are not close to the Equator. If there is a contest between socialism and capitalism for me socialism has done far more harm. It doesn’t mean that I agree with everything about capitalism. There are people I know who have made fortunes through Goldman Sachs and that’s fine. There’s that.

In my work I don’t let politics get into it. It’s too strong a signal. If politics gets in it drowns out everything else.

CG There are images in this exhibition, which I commented to you while we were viewing it, that could be used for recruiting posters for the military.

JD Says you.

CG What does Jonas say?

JD I say that’s what I saw. I refuse to take the opposite position. I photographed what I saw.