Calixto Bieito's "Carmen" at the BLO

Controversial Production Lives Up to Expectations

By: David Bonetti - Sep 29, 2016

Carmen

Music by George Bizet

Libretto by Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halevy (from a novel by Prosper Merimee)

A co-production of the Boston Lyric Opera with the San Francisco Opera

Production: Calixto Bieito; Revival director: Joan Anton Rechi

Set Designer: Alfons Flores

Costume Designer: Merce Paloma

Lighting Designer: Robert Wierzel

Fight Director: Andrew Kenneth Moss

Conductor: David Angus

Boston Lyric Opera Orchestra and Chorus with Voices Boston

Cast: Carmen (Jennifer Johnson Cano); Don Jose (Roger Honeywell); Escamillo (Michael Mayes); Micaela (Chelsea Basler); Frasquita (Kathryn Skemp Moran); Mercedes (Heather Gallagher); Morales (Vincent Turregano); Zuniga (Liam Moran); El Dancairo (Andrew Garland); El Rememdado (Samuel Levine)

Boston Opera House

539 Washington Street, Boston

Sept 23, 25, 30, Oct. 2, 2016

For its fortieth anniversary season, the Boston Lyric Opera is celebrating the best way possible – by mounting a thrilling, sexy production of a warhorse that is so vital that it makes you forget all the tired, conventional productions of it that you’ve seen before. That the opera is “Carmen,” an opera done so often that opera-going veterans approach the prospect of seeing it again with a shrug - probably because of all those tired, conventional productions - makes the achievement all the more amazing. Imagine if all the warhorses were done with the same freshness of vision. Opera houses might be full night after night with enthusiastic audiences that can’t get enough.

The Calixto Bieito production came with advance warning: it was “hot” – a critic-friend in San Francisco found it “oversexed” - and it was controversial. Originally mounted in Spain in 1999, it has been staged all over Europe ever since, from Antwerp to Dublin, from Oslo to Palermo, something one more expects of “Les Miz” than a legitimate 19th century opera. The current staging, a joint-production with the San Francisco Opera, is the first time it has come to the United States. (It did play in Bogota, Colombia, so Boston/San Fran can’t get Western Hemisphere bragging rights.)

Of course, the cynical were waiting to see if the hype was justified. Bieito is an aging enfant-terrible, a category in the theater that doesn’t mature well – look at Peter Sellars. Can a vision that first appeared more than 15 years ago still deliver the shock it originally packed?

Let me report that it can. From the very first scene in which a hunky man, wearing only a pair of jockey shorts and boots, runs with his rifle around a flag pole until he collapses from exhaustion, this show announced itself as something very different from what we’re used to. No dusty plaza outside the cigarette factory in Seville, no gaggle of choristers and extras dressed in stereotypical folkloric Spanish costumes, no hands on hips and fiery looks from heavily mascara’d eyes. This production moves the action to a dusty army post in North Africa – the dust is all that remains constant - a colonial relic of the Spanish empire, its inhabitants slowly awaking to the freedoms unleashed by the recent death of Franco, the dictator that had done his best to keep Spain in the 19th century, culturally, politically, religiously.

As Bieito – the name is Catalan - moved the scenic action 100 years into the future, he simultaneously went back to the original French text the opera was derived from, Prosper Merimee’s lurid novella, “Carmen.” The best previous production I’d seen of the work was Peter Brook’s 1983 “La Tragedie de Carmen,” which also looked back to the opera’s source. Brook mounted his radical reinterpretation of the classic on a pile of dirt in the middle of the Vivian Beaumont Theatre in New York, the feral central characters fighting for existence on a dunghill out of Samuel Beckett. Stripped of operatic niceties, “Carmen” can play as an existentialist drama – there is no exit for the central characters, who must meet and fulfill their pre-determined fates.

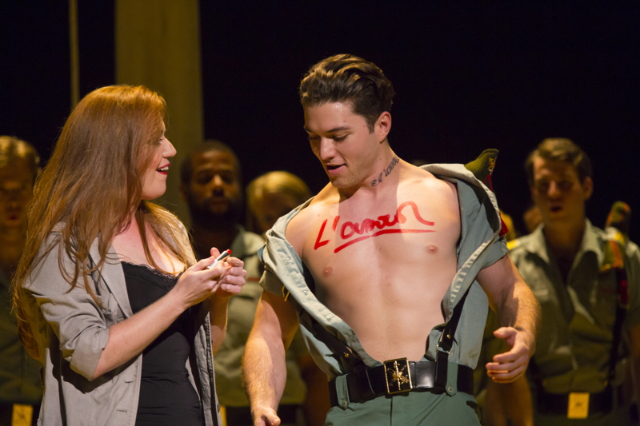

Despite the primacy of the title character – no central character has so thoroughly dominated an opera as Carmen – this is a man’s world, and the erotica so lustily displayed verges on homo-erotica, for those so inclined to see it that way. That nearly naked man in the opening scene sets the tone. Throughout the performance, half-naked men, sweaty and dusty, in their military uniforms, animate the stage pictures. At the start of Act III when a detachment of shirtless soldiers topple a billboard silhouette of a raging bull, setting up a cloud of dust, you could almost smell and taste the wave of testosterone pouring off the stage. We’ve seen this focus on primal males in all-male societies before. One of the most memorable examples is the film “Beau Travail” by the French film director Claire Denis. Also set in North Africa, the desolate landscape of Djibouti rather than Ceuta, Spain’s foothold in Morocco, it resets “Billy Budd,” a tragedy of homo-erotic longing, among a camp of French Foreign Legionnaires. The film was released in 1999, the same year Bieito premiered his take on “Carmen.” Could the film have been an influence? Or was there just something in the air?

So what is going on here? Carmen is a gypsy girl who works in a cigarette factory in Seville. She is passionate about only one thing – her freedom. She encounters a soldier, Don Jose, a corporal in a troop of dragoons, and is smitten with him – for the moment: Carmen never stays in love with anyone for long. Don Jose, however, falls deeply in love with her, and, like a puppy-dog, follows her around morosely even when she tells him to get lost. Micaela, his fiancée, comes to visit from the country with a message from his mother, learning of his unrequited love for the gypsy. In the meantime, Carmen has fallen for the toreador, Don Escamillo, the local rock-star. In the mountains, amid smugglers, Don Jose and Carmen struggle with their relationship, and he leaves the camp only when Micaela arrives, bearing news of his mother’s imminent death. Carmen’s two friends Frasquita and Mercedes read her tarot and the cards warn of her death, which Carmen greets coolly with resignation. While Don Escamillo is having his moment in the bull ring in Seville, Don Jose, mad with despondent dependency, confronts Carmen on the street outside the stadium. He stabs her and she dies. The end.

Critic Joseph Kerman once called “Tosca” a “shabby little shocker,” a phrase that is maybe even more appropriate for “Carmen.” In even the most conventional production, the shock of seeing a dramatic work based on such an amoral, asocial central character tends to wake up the opera-goers who use the opera house as a good opportunity to nap. I doubt if anyone could even close their eyes in Bieito’s production – there’s just too much to see and too much to hear. (Set designer Alfons Flores, costume designer Merce Paloma and lighting designer Robert Wierzel all deserve their props.) A prime example of a director’s opera, the singing and orchestral playing take back seats to the stage action, the stage pictures and the acting.

Pedants, of course, will complain that some text is cut, that the action has been both moved and updated and that there is so much noise covering many sweet orchestral passages. Instead, you’ve got a fleet of vintage Mercedes driving the smugglers to their mountain camp, the noise of the machines and the yellow of their headlights enlivening the opera stage. You’ve got, as I’ve mentioned, the half-naked soldiers, and at the start of Act III, while a pastorale plays in the orchestra, a soldier who strips totally naked, basking in the blue-light of the moonlight, doing toreador turns. And you’ve got crowd scenes that threaten to fall off the stage into the orchestra. The crowd gathered to watch the bullfighters parade through the streets on their way to the ring, jumping and screaming in anticipation, packs a contagious visceral excitement. (An example of the directorial freshness is that the mob lines up at the lip of the stage facing the audience. The parade of picadors, matador and others, is seen only through the mirror of their excitement.)

For this opening production of its 40th season, the BLO has moved to Sarah Caldwell’s Opera House, now home of the Boston Ballet, but mostly a house for traveling road shows, and the larger stage and orchestra pit have have allowed the company to swell. It ranks among the largest orchestra (63 players) and chorus (54 members, compared to 28 in the BLO’s last production of the opera) it has ever been able to use in a theater. And the added forces make a huge difference. The sound is tremendous, and for the first time in my six-year experience of the company, the orchestra could actually be heard. It needs to be reported that conductor and BLO music director David Angus led his enhanced forces with style, verve and drive, capturing both the French elegance of the score and its Spanish appropriations.

The BLO is now a nomadic company, presenting each of its four operas in a different downtown theater during its anniversary year. Since it left its Shubert Theatre home of the past 18 years, it is negotiating with a number of theaters as its future permanent home. It would be great for it to return to Sarah’s Opera House just for the memories – this was the same theater where we heard Regine Crespin sing Carmen - alas, an unfortunate evening for the great but past-her-time singer – the last time it was sung there. Still, the theater, originally the flagship of the RKO Keith vaudeville empire, is part of a history of opera in Boston, and it would be great if, after a gap of nearly 30 years, the BLO could add to that.

However, nostalgic as it might be, the Opera House might not be the BLO’s best choice. During the renovations made to the theater its acoustics were changed, not advantageously for live singing. As soon as the singers moved away from the lip of the stage, their sound became muted. A larger stage is a mixed blessing if it means that the performers can’t stray more than a half dozen feet from the orchestra pit when they need to sing, which, with opera, is the name of the game.

Which brings us, at last, to the singers.

Bieito’s “Carmen” is not a singer’s opera. Concept, design, acting all trump singing. Which might be just as well for a company like the BLO, which has never been able to assemble a cast of thoroughly distinguished singers. (Few companies can.)

The good news is that the central character, Carmen, upon whom the entire opera depends, was well cast. Mezzo-soprano Jennifer Johnson Cano, who last year as Donna Elvira stole the company’s “Don Giovanni,” is a distinguished singer. Cano’s interpretation of the role was cool. (How much that was Bieito’s concept and how much hers I do not know.) Her Carmen was no gypsy spitfire; rather Cano played her like an existentialist character out of film noir. She first appears on the military camp’s parade ground in a graffiti’d telephone booth, wearing not some flaming flamenco gown, but the garb of a modern working girl, her long red hair falling over a black slip dress and a putty-colored worker’s smock. (Which makes the BLO’s decision to feature her in its advertising in such stereotypical garb perplexing.)

Cano possesses a steady, focused voice with the occasional sweet little trill. Even in the famous “Habanera,” Carmen’s calling card in which she warns any prospective suitor that for her love is fickle, a Bohemian bird, and they would do well to watch out for themselves, she refrains from histrionics. It took me a while to warm to this cool Carmen, who fades into the crowd of cigarette girls, but I think Cano’s interpretation is a worthy contribution to the history of the role.

The girls had a good night in the BLO’s “Carmen.” As Micaela, soprano Chelsea Basler, who has come up through the company’s ranks, was a country girl but no patsy. Her outfit – spangly top and purple bell-bottoms - showed that even in post-Franco Spain, country girls had a sense of style, even if they got it all wrong. Basler’s Micaela was no country nun waiting for her beloved to sanctify their union. When she meets Don Jose in the first act, she gives him an aggressive kiss rather than a chaste peck on the cheek, and she is naturally and unrestrainedly physical with him. (BTW, before they separate, they take selfies at the flagpole, with the flash of the technology of the era.) When she returns in the third act determined to see the woman who made Don Jose a villain, she delivers a passionate if fearful aria, in which Basler might have offered the best singing of the evening. And when she leads her man off to return home to visit his dying mother, prematurely victorious, she leaves with a vulgar Neapolitan arm gesture, addressed toward Carmen.

Carmen’s two sidekicks, Frasquita and Mercedes, serve as her backup singers. As Frasquita, soprano Kathryn Skemp Moran, threatens to steal every scene she’s in, not so much for her singing, which was fine, but because of her performance moxie. Her outfit, a tight dress with a short skirt patterned with red roses on a white ground and her spiky bleached blonde hair, sketch a type – “modern gypsy” I guess you could call it. But it was her pair of go-go boots that defined her. In them, Frasquita is empowered – she doesn’t walk, she seems to dance from scene to scene as if she is doing the pony wherever she goes. As Mercedes, mezzo-soprano Heather Gallagher, was fine, but she got overshadowed by her gal-pal. She just couldn’t compete with those go-go boots.

The boys, were vocally the weak links of the evening. Any singer playing Don Jose has a built-in problem: Don Jose is a wimp, a mama’s boy who falls in love with the first siren who throws him a cassia flower. Tenor Roger Honeywell didn’t do much to fill out that two-dimensional definition. A fair-skinned blond, he didn’t look right for the role, and his tentative, gruff singing didn’t bring it to life. His voice was unsteady and uncertain as it rose, although he did deliver a couple of sweet if effortful high notes.

We’ve heard baritone Michael Mayes before: as its title character, he bellowed his way through the BLO’s “Rigoletto” a couple of years ago. And he’s returned to bellow his way through his role as Escamillo. To his credit, Mayes is a persuasive actor, and in a production like this one where singing is of secondary importance, he brought a sort of crude bluster to the role of the provincial bull-fighter, a narcissistic blowhard. (It’s a type familiar from a certain presidential candidate.)

Anyway, it’s a stretch to believe that a woman of spirit like Carmen could fall for either man, both clearly inferior to her. Maybe that’s why she can’t stay faithful to either.

In smaller roles, Andrew Garland and Samuel Levine, as a pair of smugglers did what they had to do, Garland exceeding expectations. And as a pair of army officers, Vincent Turregano as Morales and Liam Moran as Zuniga were appropriately butch although I have to admit they looked so much alike I lost track of which one was which. And in the silent role of the inn-keeper Lillas Pastia, Yusef Lambert was appropriately greasy. In his dirty white suit and hat, he exemplified the used car dealer stereotype, and he had a fleet of dusty, dented Mercedes to sell you.

“Carmen” is a dense, complex work, and it can be presented in many ways. In the Bieito production, the sweet, lyrical traditions of the French opera-comique, out of which the work developed, gets buried, although it survives, primarily in the orchestra, but also in some charming ensembles of female voices.

The theme of fate, which structures the work, can get lost in other productions, but in Bieito’s existentialist vision, it comes to the fore. The final scene, set outside the bullring as Escamillo has his triumph is the pay-off. Instead of the crowded over active scenes that proceed it, the final scene is stark - black backdrops and cruel bright lighting. Frasquita and Mercedes nervously warn Carmen that Don Jose has been sighted and that she had better flee. She shrugs their concerns off – after all, their game of tarot showed her that her time was up. Don Jose enters, he tries to win Carmen back, she rebuffs him. On the harshly lit stage, the field where we all meet our fates, he slits her throat, she falls, and he drags her off the stage to meet his own inexorable fate.