Ellsworth Kelly at the MFA

Museum School Alumnus Shows Wood Sculptures

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 30, 2011

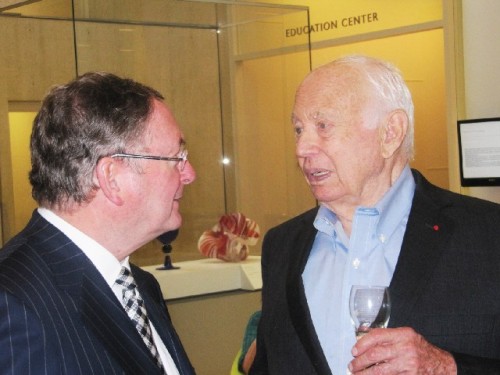

During the opening of the Linde Family Wing for Contemporary Art Edward Saywell, chair of the Wing, discussed the first special exhibition in the newly renovated space.

“Ellsworth Kelly has created a total of 30 wood sculptures, the first in 1958, and the most recent one in 1996” he told the media. “Of these 19 are on view.”

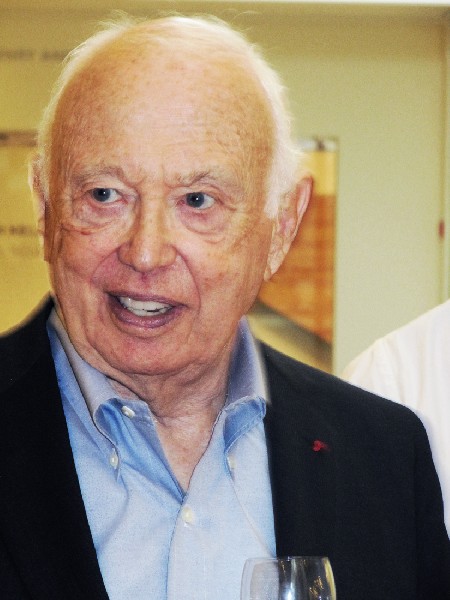

The artist, who was born in 1923 attended Pratt Institute in Brooklyn from 1941 to 1942. On New Year’s Day of 1943 he was inducted into the Army serving through the end of the war in Europe. On the GI Bill he returned to the US and completed his study graduating from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in 1948. He returned to Paris where he continued on the GI Bill for the next six years while rarely attending classes.

The museum recently acquired a major work “Blue Green Yellow Orange Red” from 1968. It is representative of his use of non rectangular multiple panels of flat vibrant color. This signature style locates him within the trend for minimalism but with the unusual element of high chroma color.

In a museum collection paintings and sculptures by Kelly are instantly recognizable. Less familiar are his sparing line drawings which reveal an obsession with the shapes and forms of nature. They have been compared to the drawings and collages of Matisse. It may be an aspect of the legacy of six years spent imbibing the School of Paris.

What is not widely discussed are his roots in Boston Expressionism and how he evolved from figuration to abstraction.

The discourse with the artist was both a revelation and an embarrassment. While Kelly, who was on hand for the opening, spoke with passion about his study with Karl Zerbe the museum has passed decades giving short shrift to the Boston Expressionists.

When this was pointed out to Malcolm Rogers in an interview during the opening he made the point that that those artists (Zerbe, Hyman Bloom and Jack Levine) are on view in the museum. Well, barely.

Yes there is token representation but the MFA has damned Boston Expressionism with faint praise. So the comments of Kelly were all the more resonant and appreciated.

After being introduced by Rogers we learned how Kelly ended up in Boston.

“I was on a boat coming home (from Paris after the war) and somebody gave me a copy of Esquire magazine” he said. “There was an article on Karl Zebre. So when I landed in New York I came to Boston and met Barbara Swan (wife of Alan Fink of Alpha Gallery.) She said ‘You’re going to stay here.’ We painted in the attic here (in the museum) and the first painting I made was one of the best I ever did because I was free and hadn’t yet found out how bad I was. Karl Zerbe was a great teacher and a perfect drawing teacher. He taught me how to see. He said 'You don’t know how to see.' "

Later we approached Kelly to follow up on his thoughts about Zerbe. We were amazed that he had attempted to make expressionist paintings. “I tried very hard. I did quite a few paintings like that.”

Kelly elaborated on what Zerbe had taught him about drawing and how that is key to his work. Looking down the length of the I.M. Pei designed Linde Wing he pointed out the window shape at the end of the barrel vaulted ceiling over the atrium. It is the kind of form that interests him and appears in the work. Which is why he was so involved with drawing. He is of the generation close enough to the masters from Matisse and Picasso to Mondrian who evolved from natural forms to abstraction.

“So you are not an abstract artist” I commented to him rhetorically. He seemed a bit taken aback at the suggestion of representation and figuration in the work.

"I think abstract is just the opposite of naturalism or figurative” he replied. “I can't stand figurative work. It's been done."

His response recalls an exchange between Jackson Pollock and the artist/ teacher Hans Hoffman who told Pollock “You should work from nature.” To which Pollock responded “I am nature.”

While studying with Zerbe Kelly recalled “When I was drawing he would come up and say ‘You’re not getting it.’ And he would make three lines. I feel drawing is the foundation of all my work. I draw constantly. Not so much now.”

Malcolm Rogers asked him “Did you study in the museum when you were here?”

“Yes and it was wonderful” Kelly answered. “During lunch hour to come down (from the MFA’s attic) and looked at Renoir. There is a beautiful one of a couple dancing and cigarette butts on the floor. (Ground actually as the couple are dancing at an outdoor café.) I love that painting. (“Le Bal a Bougival”) It’s one of the best Renoirs. I also painted a copy of a Tintoretto. A head about this big (shows scale with hands). That was for a class in design. I also did a copy of a gold leaf painting by (Ambrogio) Lorenzetti. I spent a whole summer doing that. Mother and child. A shaped painting with a triangle on top.

“Later on, it started in Paris, I did two paintings in red and orange that were started together. With some other colors. And another one which was white and black. I did a book in 1951 Line from Color for which I tried to get a Guggenheim. I didn’t get the Guggenheim. But I showed the book to Hans Arp. He went through the book. It’s 40 pages. MoMA now has all the collages. He stopped at the "Orange" and said ‘This is just two colors.’ I couldn’t say anything."

But he returned to that thought at a later time.

”I was with Diane Waldman, the curator of my exhibition at the Guggenheim (1996). We were in the National Gallery in London in a room full of orange and pink paintings by Lorenzetti and I said to her ‘That’s where I got it.’ Without knowing it I did those two colors. The painting with the gold leaf. I gave it to my mother and I don’t know where it is now.”

The beginnings of the work that Kelly is today know for started in France. It was time to come home and launch a career as an artist.

“I heard about Black Mountain College” he said. “But I had spent six years in Paris and was so out of touch with what was going on in America. I got on an airplane and landed in New York. I was headed to Black Mountain College. My life would have changed if I went there. I knew John Cage in Paris. He had written ‘Come back to America. There are some interesting artists including Rauschenberg.’ "

Kelly never got to Black Maountain college after visiting with Rauschenberg. “He was the first person I went to see and he was doing all these Combines. It was hot in August and he was in shorts covered with red paint. He said let’s get you a studio.”

The artist had his first one man show in Paris at Galerie Arnaud in 1951. He had his first New York show at Betty Parsons Gallery in 1956 and another with her the following year. That earned him recognition and inclusion in “Young Americans 1957” at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The oldest of the 30 wood sculptures he created was made in 1958.

The wood sculptures represent a paradox. His work is known for its strong and simple high chroma monochromes and distinctive geometric shapes. The wood presents an enigma. Is there an absence of color or is the artist interested in the inherent color of the wood itself? In that sense are they sculptures or, in the case of the wall mounted works, a variant on monochrome paintings?

Given the limit of elements he entices us to work with it would be difficult not to pay close attention to the surface, color and texture of the wood. The natural material in some ways is more satisfying that the artificiality of the very specific selections of color. To paraphrase Pollock, about the sculptures, Kelly might well remark “I am nature.”

But, of course, he didn’t.

Instead he told a group of critics “I try to do as little as possible to the wood... I don't like circles because I feel circles are too finished. You can't do anything with it. But a square you can do something with. Curves are fabulous.”

Adding that "Shadows are very important. Shadows are always contemporary, modern, abstract... The marks in the wood grain are at least 100 years old, but the curves are today.”

As we toured the exhibition so beautifully installed at the MFA it was poetic to consider that such a distinguished career started upstairs in the attic. And a summer spent sweating over a Lorenzetti. Amazing how things come back full circle. Which, yeah, I know, sometimes feels too finished.

Indeed, the shape of things.

Nature.

Which is to say that Ellsworth Kelly in Not an abstract artist. Go figure.