Alan Gilbert Conducts the New York Philharmonic

Emanuel Ax, Pianist

By: Susan Hall - Oct 01, 2009

New York Philharmonic

Avery Fisher Hall, New York

September 30, 2009

Magnus Lindberg, EXPO

Charles Ives Symphony No. 2 and Unanswered Question

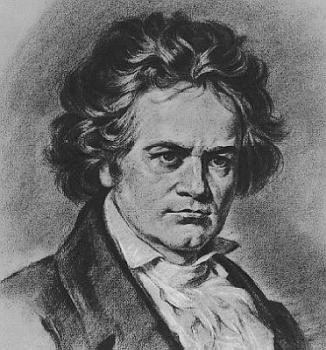

Ludwig Beethoven, Piano Concerto No. 4

Alan Gilbert, Conductor

Emanuel Ax, pianist

On September 30 the New York Philharmonic presented EXPO, the new Magnus Lindberg work, the Charles Ives' Second Symphony, Ives' Unanswered Question and Beethoven's 4th piano concerto performed by Emanuel Ax. The now not-so-new musical director, Alan Gilbert, conducted.

In his fourth concert, Mr. Gilbert's method begins to become clear. The audience is being embraced as part of the Philharmonic. We will hear some things old, some things new, some things that borrow -- tonight Ives' potpourri of band music, military music, folk songs and barn dances and yes, blue -- most music has its sad moments.

The evening's program began as Mr. Gilbert took the stage with the Philharmonic's new composer-in-residence, Magnus Lindberg. They engaged in a dialogue about Mr. Lindberg's work, particularly EXPO which would begin the program. This was a reprise of a piece which heralded the Philharmonic's new season and its opening clash suggests that attention must be paid -- not only to this piece, but to music in general.

Giving yourself over to active listening is well worth the effort. Mr. Gilbert is going to help us understand. Because both the Ives Symphony and his Unanswered Question are inconclusive, Mr. Gilbert's observation that EXPO was shaped to ends and conclusions directed us to shape our ears. The composer's interest in melody as well as harmonies clearly differentiated EXPO from the Ives Symphony which would follow.

EXPO this evening was like listening to nature – with the bee-like buzzing and humming and zooming of strings until they finally settled down. The strings and brass are often in dialogue.

Dialogue may well have been the evening's theme. The Ives' Symphony is classic in construction, but into the form Ives has brought bits and pieces of all the music he'd heard and loved: Stephen Foster songs, barn dance tunes, Columbia Gem of the Ocean and themes from the old camp meetings.

Ives broke the conventional symphonic frame with these beloved hymns and marching songs he'd heard in downtown Danbury, Connecticut where he grew up. On Sundays he would listen to the music coming from twelve churches surrounding the town square and enjoy choirs singing on top of and against each other. This is a heterogeneous symphony for a melting pot. Ives was hurt when Serge Koussevitzky chose Roy Harris to compose a patriotic symphony for the Boston Symphony. Mrs. Ives, ever her husband's advocate, wrote to Kuss A viTZKey suggesting the Second, but did not succeed in convincing him.

The performance of the Second Symphony was delightful -- warm and humorous under Mr. Gilbert -- and brought forth emotions ranging from exuberant laughter to tears. One listener wanted to stand up and yell.

Mr. Gilbert approaches music with a strict adherence to time and shape, but then brings forth inspired, passionate and unexpected, but delicious sounds from the orchestra. The style recalls Sir Georg Solti and current music director of the Boston Symphony, James Levine. Their love of all music is palpable.

This Ives Symphony has a long history with the Philharmonic. Leonard Bernstein premiered the composition as a guest conductor in 1951 and it was in his first program as music director in 1958. Mrs. Ives wrote Bernstein after the performance in a letter dated 2/11/51. "It was a wonderful and thrilling experience to hear Mr. Ives and Symphony as you conducted it...I have been familiar with it -- in snatches -- for forty years and more...to hear the whole performed at last was a big event in my life. People did like it, didn't they? Someone wroteÂ…that its hearers are participators in it."

Luemily Ryder lived next to the Ives' in West Redding, Connecticut. She recalled Ives coming to her house to hear a re-broadcast of Bernstein conducting the Second. "After it was over, I'm sure he was very much moved. He stood up, walked over to the fireplace and spat! And then he walked out to the kitchen. Not a word."

Not everyone had shared Bernstein's enthusiasm for the composition. Ives begged conductor Walter Damrosch (he's a member of the family for whom the band shell in Lincoln Center is named) to rehearse the piece with the New York Symphony. Damrosch wrote back, "Pay the musicians and I'm sure they'll do it." Ives had send Damrosch his only clear inked copy, which Damrosch promptly lost. Years later, composer and conductor Bernard Hermann, who wrote scores for films Citizen Kane and Psycho among others, went to Damrosch's home in search of the score, and there it was in the cupboard where Damrosch had put it 40 years earlier. Mrs. Ives, on her list of letters to be written, referred to Walter as Damnrot.

As Ives breaks the symphonic frame seriously (Mozart did it as a joke), he creates a dialogue between conventional symphonic form and the cacophony of our American vernacular music. The Unanswered Question has dialogues between strings and flutes and a trumpet.

We had been alerted by Mr. Gilbert that he intended to present Ives' Unanswered Question and the Beethoven back to back without a break. How was he going to do this?

After the intermission Emanuel Ax arrived on stage and sat at the piano to listen to the Ives. The Unanswered Question is clearly a dialogue between strings and flutes and a trumpet. I have never heard strings play so quietly, forcing us to strain to hear, to pull us in. So too, there would be passages in the Beethoven in which Mr. Ax was inspired to play almost inaudibly. Attention must be paid. Yes.

Clearly the Beethoven is a dialogue between the piano and the orchestra. The unexpected opening by the piano, in which the pianissimo of the Ives was echoed, is an intimate invitation by composer and performer into this magnificent piece. Ax, like Beethoven, is a terrific pianist, and there was no need for the impressionistic past commentary -- fates knocking at the door, Orpheus taming the Furies have been mistakenly suggested.

The second movement has a clear dialogue between the piano and the strings. Mr. Ax moved with the orchestra when he was not playing -- as though he wanted to physically convey his listening stance.

Back and forth the dialogue continues—the piano steadfast, the strings gradually weakening. Then the piano unleashes a short, wild cadenza. Piano and orchestra play together, sharing the same chords and the same rhythm. Over the last chord, the piano poses a brand new question, to which Beethoven responds by launching into the finale without a pause.

So Mr. Gilbert presented answered and unanswered questions in the musical dialogue. If you are willing to be educated, to be open to innovative music of the present and past, the new music director is clearly going to help you appreciate it.

Great teachers can make anything interesting. They have a dialogue with their students. They modestly instruct by enticing, delighting, pushing. Among Mr. Gilbert's many talents is great teaching. The Philharmonic concerts are a real treat!

This program will be repeated on October 1 and 3. On October 2 Mr Gilbert takes the orchestra to Caramoor.