Mongolia Part One

Ulaanbaatar and Gorkhi-Terelj National Park

By: Zeren Earls - Oct 01, 2016

Those of us who had spent a week in China’s Yunnan Province flew on to Beijing, where we met nine others arriving from the US for the main part of our itinerary to Mongolia. Arriving at 10:30 pm in Beijing with hand luggage only, we spent the night at Hejing Fu Hotel to make our connection at 8:15 am to Ulaanbaatar, the Mongolian capital. Knowing how busy the Beijing airport is at all hours, we had been able to prudently check our main bags directly from Kunming to our final destination.

As the plane approached the Chinggis Khaan International Airport at the end of a 3½-hour-long flight, we could see the River Tuul emerging below with buildings on its banks amidst lush greenery. Setting our watches one hour ahead, we landed at noon local time. After we had gone through customs, our Mongolian trip leader, a young man of medium stature called Damidaa (Damda) Dashpuntsag, met us with a big smile, his braces showing as he grinned. Piling in to a big red bus, we headed toward the city 20 km away.

Noting the road repairs along the way, Damda commented that “UB" (Ulaanbaatar) was busy preparing to host an international conference on global issues among 53 countries – 28 Asian and 25 European. The bus pulled up in front of the Kempinski Hotel Khan Palace, an affiliate of the worldwide luxury hotel chain founded in Germany. When I stepped into my spacious room with every amenity one could think of, including a warm toilet seat, I knew the three nights spent here would be special, given that the rest of the trip was to be in the countryside.

Following lunch at a local restaurant with waiters in full traditional regalia, we went for a walk to get acquainted with the urban neighborhood. The imprint of past Chinese dominance as well as that of more recent Russian control were evident all around. Chinese-style houses with turned-up eaves shared the skyline with socialist era buildings. Mongolian nomadic felt tents, called ger, abutted modern dwellings. Names of streets and stores were all in Cyrillic characters, which were introduced as the official alphabet by the Soviet regime in 1941, replacing the classical swirling vertical Mongolian letters. Although Mongolia has been an independent country since 1989, the language is still written in Cyrillic with a few exceptions, such as commercial logos.

Later on at the hotel, Damda briefed us on our two-week adventure trip, beginning with a ceremonial welcome in which he held a long blue silk scarf, symbolic of the open sky, across his arms and then made the rounds kissing each of us on both cheeks. Then he talked us through the itinerary within the hand-drawn borders of the country on a chalk board, noting important facts. UB, established in 1639 as center of Buddhism and the first capital of the Mongolian Empire, had first been a nomadic encampment. It settled into its current location in 1778, and is now a metropolis of a million people. The nomadic way of life nonetheless still remains the norm for about 30% of the country’s population.

Our morning tour began at the Gandan Monastery, built in 1838 as an important center for the entire Mahayana Buddhist community. In 1938, the Communists suppressed all religious activity, destroying monasteries and executing monks. In 1990, after the Democratic Revolution, Buddhism flourished once more, and the Gandan Monastery was restored. Currently there are several institutes and temples at Gandan and 900 monks. During our early morning visit, we watched the monks arrive for work, which began with a call to prayer to the sounds of gongs from a tower. The grounds became animated with the faithful people spinning prayer wheels and walking around incense cauldrons. We quietly stepped into the imposing main temple, where monks, seated in rows across the room, chanted sutras under the gaze of an 87-foot-high gilded statue of Janraisig, the Bodhisattva of Compassion – an arresting spectacle it was.

The tour continued on to the National Museum of Mongolia, which covers the history of the land and its people from ancient times to the present. The extensive collection, displayed in nine exhibit halls, includes archeological and ethnographic artifacts of those who have made an imprint on this land, including people of Turkish origin, such as the Uyghur Empire. Traditional clothing and jewelry, including ceremonial costumes of Mongolia’s more than 20 ethnic groups, along with a hall displaying elements of pastoral nomadic life style, are especially engaging. The museum has a good gift shop, where I purchased an embroidered suede bag, a T-shirt decorated with the classic swirling vertical letters spelling Mongolia, a small replica of a Buddhist dance mask, and a small morin khur or horse-head fiddle – a traditional stringed instrument with tuning pegs carved into the form of the head of a horse and a bow and sound box strung with horse hair. At the favorable exchange rate of almost two MNT (Mongolian tugrug) to one USD, the total for my purchases was under $60.

Sukhbaatar Square, covering 334,413 square feet and named after the patriot, Damdin Sukhbaatar, known for the 1921 revolution against China, is the heart of Ulaanbaatar. A statue of the hero rising on his horse is the central feature of the square, surrounded by the Parliament building and the stock exchange. Now renamed after Genghis Khan, the square was also the site for the uprising against Soviet control in 1989 and continues to be a place for rallies and ceremonies. During our visit city employees were busy setting up barricades and chairs for a concert of western music later that evening. Large groups of Mongolian visitors milled around the square, posing for pictures in front of the Parliament with Genghis Khan’s statue at the top of the front steps.

The luxurious surroundings of the Kempinski Hotel provided well-deserved free time following our morning walk-about, in preparation for our evening outing to a Mongolian folklore performance. Held at the Red Theater, built by the Russians in the 1950s and named for the dominant red color throughout, the spectacle was a showcase of folkloric dance and music with elaborate costumes and unique musical instruments. Among the highlights were a Buddhist tsam (masked) dance to exorcise evil, an amazing contortionist, and the sounds of horse-head fiddles and guttural throat singing, where a singer produces two or more notes simultaneously through specialized vocalization techniques, resulting in unique harmonies.

In the morning we drove about 35 km southeast of Ulaanbaatar to the region of Nalaikh to visit a monk at the Sain Nomun Monastery. The yellow building, atop a hill with sweeping views of its surroundings, was built in 1992 for the followers of “yellow sect” Buddhism, confined to practicing behind doors until the 1990 revolution. The monastery’s second-highest ranking monk met us, giving an introduction to Buddhism through his own life story. He had begun studying Buddhism at the age of eleven and had been practicing it for the past twenty years. Once you begin to follow the right path, he explained, there is no going back. Attaining each of the four levels of Buddhism depends on the number of things one is able to abstain from, ranging from marriage at level one to 200 things at level four. Reincarnation depends on the level of abstinence attained in life. The monastery has a school for 50 students, beginning at age 16. They learn Tibetan sutras and ritual practices, as opposed to those in Sanskrit.

A visit with a Kazak family introduced us to the Muslims of the region. Nalaikh used to be a coal mining area, attracting Kazaks living near the border to come and work in the mines. Although the mines are closed now, many Kazak families have stayed on, making up a third of the town’s population of 28,000. Our hosts, one such couple in their 70s, had settled and raised six children here. Upon entering their ger, topped with a crescent identifying their Muslim affiliation, I was amazed at the hand-embroidered wall coverings that completely surrounded the interior – all made by one person. We settled around a table to enjoy appetizers, followed by a hearty soup. Then the two granddaughters, ages 7 and 5, danced in native costume for us, and the grandson, in his teens, played the oud. Dressing us in Kazak costumes added to our fun.

Thereafter we headed north toward Gorkhi-Terelj National Park, for the first of several ger camps on the trip. On the way we stopped at an ovoo to observe the customary circling three times in clockwise motion of a sacred stone heap in order to have a safer journey. Mounds of rocks topped with blue scarves and used as altars or shrines are part of the Mongolian nomadic culture and relate to shamanistic beliefs. They serve mainly as sites for the worship of Heaven and lesser gods, led by shamans. When people visit these mounds, they pick up a rock from the ground and add it to the pile, sometimes leaving offerings such as sweets. During Heaven worship ceremonies, blue scarves tied to a stick are placed at the tip of the sacred mound.

Traveling in a big bus, decorated with purple and white accents throughout, including the curtains, we reached camp Alungoo in Terelj National Park. The camp staff, one of them dressed in native garb with a blue scarf across her arms, welcomed us with cool washcloths and fruit juice. My sleeping quarters, a round space with a wood stove in the center, were simply furnished with a double bed, a small cupboard, and a number of felt throw carpets. When we met the staff on the terrace of the camp lodge later on, they were all in traditional costume and encouraged us to dress like them, giving us similar clothing. I quickly stepped into the ceremonial welcome role, wearing an elaborate beaded hat and a blue silk scarf across my arms, against a backdrop of green pastures.

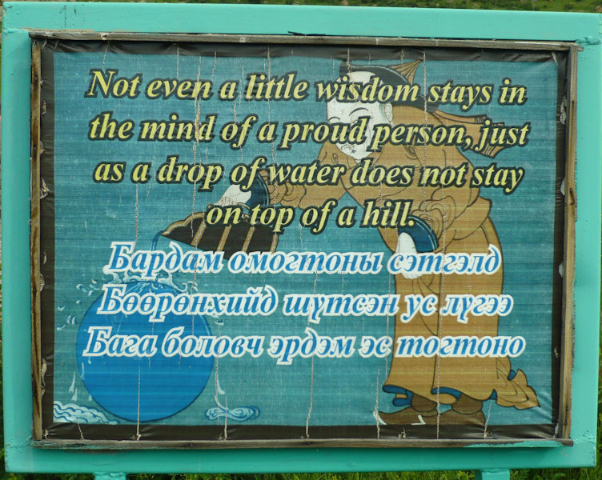

The morning excursion took us through Terelj National Park, a nature reserve set in a deep valley with mountain streams, green hillsides, and granite boulders, one of which is shaped like a giant turtle and known as well, Turtle Rock. After visiting the big “turtle,” we hiked to Aryabal, a meditation temple rebuilt in 2004 after the Communist destruction of 1939. At the end of a long walking path that leads to a steep set of stairs is the entrance to the temple. The path is also designed for meditation and reflection, and is lined with signs that highlight Buddhist teachings, written in both English and Mongolian. Each sign encourages contemplation, reminding the reader to focus on spiritual life. The rocks above the main temple are decorated with paintings of gods and guardians, and intricate carvings adorn its wooden posts and beams. Paintings of arhats or enlightened masters, depicting stories of their lives, adorn the interior of the temple, which has a meditation cave next to it.

Following lunch back at the camp, we visited a local nomadic family in their ger to learn how to make cheese. As fresh cow’s milk boiled over a wood stove, we watched our hosts skim the cream that formed on top, which we then enjoyed as clotted cream, scooping it up with cookies. Meanwhile, stirring in a small spoonful of yogurt helped ferment the hot milk, which was strained through cheesecloth and placed under a heavy rock to rid it of excess water, producing a block of fresh cheese ready to be cubed into bite-size pieces.

Our guide Damda, wearing a bandana with a US flag print, reminded us that it was the 4th of July, which we were to celebrate back at the camp. Our treat was a rectangular cake decorated with stars and stripes, which followed dinner consisting of a bean plate with tofu, vegetables, barley, and green salad. Roasting marshmallows and small-scale fireworks ended the festivities.

On the last day at camp Alungoo, we ventured to a historic site where the Mongolians have erected an equestrian statue of Genghis Khan, which stands at 131 feet atop a 33-foot-high coliseum. According to legend, this is where Genghis found a golden whip, which inspired his future conquests accompanied by vultures and eagles – the former a sacred bird for the Kazaks and the latter revered by the Mongols. The multi-level coliseum has a museum in the basement, with photographs of petroglyphs found in central Mongolia and dating from 40,000 years ago. The grand lobby on the first floor has a larger-than-life-size model of Genghis’s boot. A mammoth sculpture of Genghis on the terrace level commands a spectacular view of the surrounding pastures with nomadic gers sprinkled throughout. The reverence to Genghis Khan and the use of his name, suppressed during Soviet time, have been popularized since Mongolian independence, turning it into a brand name on beer and vodka bottles.

Our visit with a horse-breeding family was an eye-opener for a city-dweller like me. When we arrived, all the women were milking the mares, a job they must do every two hours, while men were taking care of the horses. Nomadic children learn to ride and capture horses at a very young age. They use a pole-lasso during the day to help round up the horses, which are let loose at night, as there is no fencing. The family, who moved seasonally in May and October, hosted us in their ger, where we tasted fermented and fresh mare’s milk – the former very sour, the latter sweet. We then enjoyed biscuits by dunking them into fermented milk pressed in a container and mixed with cream – delicious it was.

Our farewell dinner at camp was an introduction to the Mongolian hot pot meal, which is a layering of chunks of lamb, seasoned with garlic and bay leaves, and smooth stones, heated in a wood-burning stove. Water is added to the alternating layers, which cook in a pressure cooker for one hour.

While waiting for our food to cook, we learned how to take apart a ger and put it back together, a procedure essential to nomadic life. The first step was to peel away the heavy plastic and thick felt that envelope a frame, which stretches and collapses like an accordion made of wood strips. Heavy center poles hold up a circular roof structure made of more wood strips, these anchored to the ground with ropes without digging, so as not to hurt the ground. Inside the ger, a heavy rock at the center weighs down the roof to keep it from blowing away. In sum, these are practical homes for pastoral people, who live by and for their livestock.

Returning to our hot pot meal, we enjoyed a very tender, succulent lamb dish, accompanied by baby carrots, broccoli, cabbage, and potatoes, followed by watermelon for dessert. Although the Mongolian diet is heavily weighted on dairy and meat, our camp meals were an exception.

In the morning, the camp staff bade us goodbye by sprinkling milk with a ladle after us to wish a good trip. We returned to Ulaanbaatar in order to fly north for our next adventure to Lake Khövsgöl, a large fresh water lake near the Siberian border.

(To be continued)