Brazil: Part One

Salvador da Bahia

By: Zeren Earls - Oct 02, 2015

Brazil had been on my short list of countries to visit for some time, so when the opportunity arrived to join my artist friends from Seattle to explore three of the country’s distinctive cities — Salvador da Bahia, Rio de Janeiro, and Curitiba — my decision was swift. In late August I flew from Boston to Washington, DC to get to Sao Paulo, Brazil’s major hub for international flights. Fortunately for me, the flight was not full, so I was able to stretch out in the middle section of the plane and slept for about six hours during the nine-hour overnight flight. At the end of a two-hour domestic connection, I finally arrived in Salvador, thus ending the almost 24-hour journey from Boston at 2:45 pm Brazilian time, one hour ahead of EST.

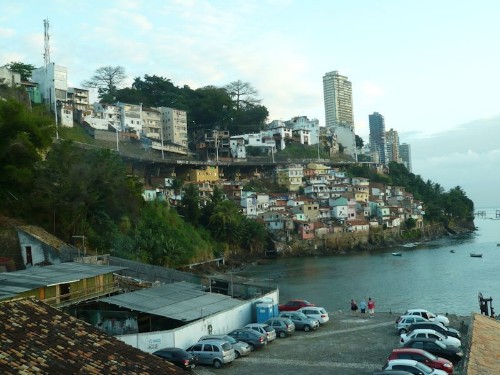

Salvador is right on the Atlantic Ocean. On the ride to the Barra district — where our hotel, the Monte Pascoal, was located — my first impression was one of sensory overload as we approached the closest beach to downtown. Lush greenery was all around, along with pockets of visible poverty with run-down houses and shops, plus beach umbrellas as far as the eye could see. The boardwalk teemed with people jogging or walking, with or without dogs, some pushing strollers. Musicians entertained passers-by. Sidewalk cafes and bars overflowed with conviviality as locals enjoyed a beer after work. Enticed by the festive ambience, I went back out as soon as I dropped off my bag. As I made my way through the crowds, I noticed my friends, who had arrived earlier, at a sidewalk restaurant. I joined them over a bowl of clams in broth with a choice of garlic or pepper sauce, thus ending my long day on a delicious note.

Salvador was built on the cliffs of a peninsula, first discovered by Amerigo Vespucci in 1501, and became the capital of Brazil in 1549, when the Portuguese court sent the country’s first governor general. It is now the capital of the state of Bahia, Brazil’s fourth largest city, with a population of over 3 million. Salvador, meaning ‘savior’, is renowned as the center of Afro-Brazilian culture, with a mixture of black and white races descended from Africans, Europeans, and Native Americans. This rich blend gives the city a unique character shaped by exuberant colors, sounds, rhythms, and flavors.

Our tour began in the Upper City, known as the Old Town, which faces All Saints’ Bay, named in honor of November 1, the day it was discovered. From the Upper City there is a panoramic view of the Bay and the newer Lower City, where Mercado Modelo, the city’s large craft market, is located. A free-standing art deco elevator connects the Upper City to the Lower City for those who do not want to descend the steep streets on foot.

The Historic Center of the Upper City, known as Pelourinho, is a UNESCO cultural heritage site. It is known to have the largest collection of baroque buildings in the Americas, as it was the seat of the government and a fashionable residential district when the city served as the country’s first capital. 800 colonial buildings dating from the17th to the 19th century have been restored.

Starting our walking tour at the Terreiro de Jesus, a large plaza framed by three of Salvador’s most famous churches, we visited the largest, the Cathedral Basilica, which is a 17th-century Jesuit structure built mostly of stone, with gold-leaf work on the main altar. On the north side of the Terreiro de Jesus is the Afro-Brazilian Museum of Archeology and Ethnology, which has a collection of objects that highlight the strong African influence on Bahian culture, including masks, carvings, musical instruments, costumes, and other artifacts that form part of the condomble religion. There are also wooden panels carved by Carybe, an Argentinean artist, who has adopted Salvador as his home. A special installation showing a black teenager behind bars calls attention to the mysterious disappearance of many of the city’s young people.

On the adjoining square, the Praca Anchieta, are the opulent baroque Church and Convent of San Francisco. The interior of the highly decorated 18th-century structure has intricate wood carvings encrusted with gold leaf, a gilded high altar and a painted ceiling with scenes associated with the Virgin Mary. Blue-and-white hand-painted Portuguese azulejos (pictorial tiles) depicting scenes from the life of St. Francis, combined with elaborate wood carvings, adorn the choir. The tiles also surround the courtyard of the convent annexed to the church.

Next door is the Church of the Third Order of St. Francis, which has an impressive carved facade with statues of saints, angels, and other sculptural ornaments. Short distance away narrow cobbled streets, lined with storefronts and sidewalk vendors lead to the Largo do Pelourinho (Pillory Square). This small plaza commemorates the signing of the decree that officially ended slavery in 1888. It was on this spot that runaway slaves were tied to a pillory and publicly beaten. The Casa do Benin (Benin House) highlights artifacts from the Old Kingdom of Benin, now southern Nigeria, where most slaves were shipped to Bahia.

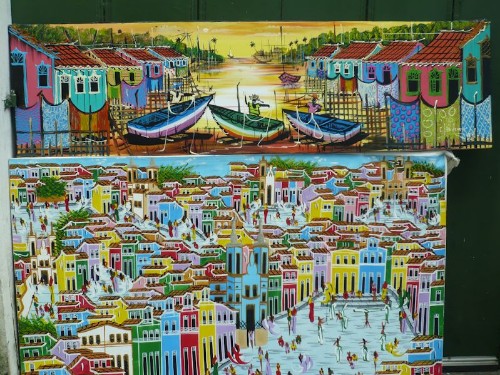

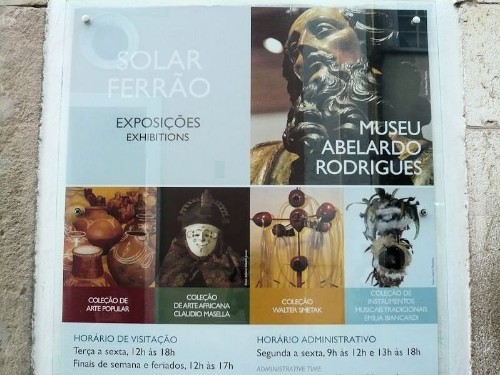

A charming area with colorful facades lining steep, meandering streets, Pelourinho is dotted with women in distinctive hairdos or wearing bandanas and puffed-up skirts. Enjoying the local scenery, we arrived at the Abelardo Rodriguez Museum of Sacred Art, housed in the 17th-century church and convent of Santa Teresa. Carved wooden images of saints, paintings, ivory sculptures, and works in earthenware, silver, and gold, in addition to folk art, are on display in what is claimed to be the largest collection of sacred art in Latin America.

Our lunch stop was at a traditional restaurant with rustic decor, where we tried the local specialty, bobo de camarão, made of shrimp and mashed manioc cooked in coconut and palm oils. The hearty dish was delicious. Meanwhile, loud drumming on the street prompted us to dash to the balcony of the second-story restaurant. A banner leading a parade of musicians and dancers called attention to an upcoming three-day festival of American Black Art, including cinema, dance, music, theater, and exhibitions. The banners were followed by drummers, people playing shakers, and performers of capoeira, a Brazilian martial art that combines acrobatics and dance.

For the rest of the afternoon we meandered about, browsing in shops. Thanks to the exchange rate of about 3 to one favorable to the dollar, I was able to buy a multi-colored hand-knit linen top for a fraction of what a hand-made item would have cost in the States. Having made a purchase, I was allowed to take a picture of the shopkeeper in her typical Bahian hooped skirt.

Crossing one of the squares, we ran into youth groups rehearsing for the festival. Among the spirited performers, most of the dancers were girls and the drummers were mostly boys, with the exception of a few girls in the front row. Nearby were vendors of a typical street food called acaraje, a type of Brazilian falafel made from black-eyed peas. Before calling it a day, we returned for another panoramic view from the Upper City to watch the sunset over All Saints Bay, where boats were silhouetted against the shimmering orange waters of the Atlantic Ocean.

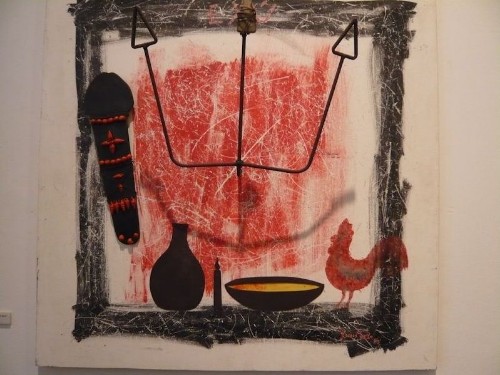

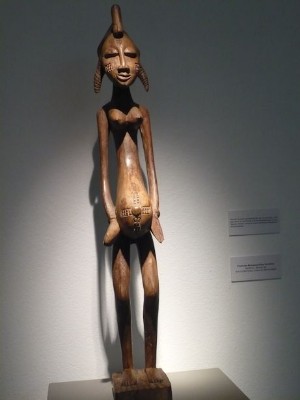

On our final day we had a morning at leisure. Some of us walked from the hotel to a nearby mall, where goods such as a pair of fashionable walking shoes sold for under $40. In the afternoon we visited several museums. The Rodin Museum is the private collection of a businessman who had Rodin sculptures in his garden. After his death and following a three-year exhibition in the museum, Rodin’s works returned to France. At the time of our visit, the museum had a temporary exhibition of sacred and secular art from western Africa, including pieces from Burkina Faso, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, and Nigeria. The museum’s garden has exotic trees and plants and features a cafeteria, where I enjoyed a shrimp salad.

The Carlos Costa Pinto Museum houses the collection of a wealthy businessman and his family. The collection includes works typical of colonial and imperial Bahia from the 17th-20th centuries. Exhibited thematically, the display consists of home furnishings, porcelain, and jewelry, including crystal and hand-painted porcelain dishes. Of special interest are silver balagandans — clusters of charms once pinned to the blouses of slave women to indicate their owners’ personal wealth. The flooring in the main rooms of the American colonial-style building, dating from 1958, is of pink Carrara marble.

Our day ended in the Lower City, where there are more churches and museums. Our last stop was at the Bahia Museum of Modern Art. From the printed schedule, the museum seems to have a rich schedule of classes and speakers on contemporary literature, poetry, book illustration, and similar topics. However, one must know Portuguese to benefit from any of these offerings. Hardly anyone speaks English in Brazil. Few museums have English wall texts or captions; brochures in English do not exist.

Evidence of faith goes beyond churches. One popular souvenir of Salvador is a colored ribbon stamped with the words Lembrança do Senhor do Bonfim da Bahia (“Souvenir from the Savior of Bahia"), which is tied around the wrist in three knots, each representing a wish. One’s wishes come true when the ribbon falls off. Sold in various colors, each type of ribbon symbolizes a deity in the Yoruba religion. The ribbon is a spiritual link to traditional Afro-Brazilian culture.

A similar spiritual link can be seen in water sculptures of various Condomble gods, reached by boat to leave offerings for one’s wishes to come true. I was able to catch a glimpse of these on the way to the airport as our van speeded by. Had I been able to take a boat to reach one of the gods, I would have wished to return to Salvador for a longer time to explore this fascinating city.

(To be continued)